The Problem

The situation in the South has been such that the master class has been able to limit severely the education and folk participation of Negroes and thus to prolong its paternalism. In that area also the ruling group has succeeded in propagating race prejudice and utilizing it effectively as a retarding cultural force. Perhaps the most confusing approach to understanding the class position of Negroes in the United States has been the assumption that race prejudice is a primary, psychological function. One would think that after the almost laboratory example of the rise and subsidence of German fascism, of how racial antagonism may be fanned to a fanatical pitch and then dramatically arrested, it would now be patently clear that the generation and maintenance of prejudice and discrimination depend upon a definable social situation.

The dominant economic class has always been at the motivating center of the spread of racial antagonism. This is to be expected since the economic content of the antagonism, especially at its proliferating source in the South, has been precisely that of labor-capital relations. The biological difference of color provides a concrete symbol upon which attitudes of fear and hate might be anchored. The dominant class, furthermore, has been explicit in its terms of living together in “peace” and harmony with Negroes. Its pivotal condition has been that the latter be content to work hard, willingly, and unorganized. “Love” tends to vanish as soon as Negroes begin to show signs of unionization, of movements for normal political status, and of desires to bring themselves up to cultural parity.

The schools, of course, are the principal institution for transmission of the culture. Accordingly, that “fine relationship” long existing between the races in the South tends speedily to come to an end when Negroes seek equal educational opportunities. As one Congressional Representative from Georgia, John J. Flynt, Jr., said in the House on February 23, 1956: “The Supreme Court decision [insisting upon equal educational opportunities for all citizens regardless of color] handed down on Black Monday, the 17th of May, 1954, did more to destroy the progress that had been made in race relations in the South than anything that has happened in the past 80 years.”

The principal conditions for development of mass attitudes of racial antipathy appears to be: (a) a peculiar variant of capitalist production; (b) an exploitable group which can be identified as culturally or biologically different; (c) monopolization of political power by a de facto ruling class; (d) control of the media of mass communication and continuous use of them to direct derogatory and discriminatory propaganda against the exploitable group; and (e) the promulgation of discriminatory laws, the most important of which make segregation mandatory. In a situation such as this the races may be effectively estranged. Each side tends thus to live in some state of endemic social distrust while interracial mass behavior involving violence assumes a continuously potential danger.

The way in which an economic situation may be hinged to racial differences may be illustrated by the following news item:

Tokyo’s big, influential daily, Yomiuri, last week [April, 1955] headlined a series of articles on a startling economic theme: “Japan is at the mercy of the blue-eyed foreigners.” The blue-eyed foreigners, cried Yomiuri, are U.S. business men in Japan, who are charging “exorbitant” royalty fees …. The vicious newspaper articles were a symptom of the worsening relations, now approaching a postwar low, between U.S. companies and the Japanese Government.

This racial situation, of course, is not identical with the one in the South, yet it is easy to sense what profound emotions are touched by injection of the “blue-eyed” element into the economic relationship. It is easy to conceive, also, how blue-eyes might, under certain circumstances, become in Japan a symbol of dishonor and even racial shame. The yellow cap and badge of medieval Jews was intended to serve similar emotional purposes. The Southern oligarchy has lost no opportunity to render the physical traits of Negroes a red cape of mass passions. Indeed, these passions have been so assiduously cultivated that they may now be evoked spontaneously among the white masses of that region.

And yet, even though it may be recognized that the pith of racial friction in the South lies in the exploitative interests of the dominant group, there have been no full-scale investigations of its processes. Professor Key refers to this process as “an extraordinary achievement of a relatively small minority—the whites of the areas of heavy population—which persuaded the entire South that it should fight to protect slave property. Later, with allies from conservatives generally, substantially the same group put down a radical movement welling up from the sections dominated by the poorer whites. And by the propagation of a doctrine about the status of the Negro, it impressed on an entire region a philosophy agreeable to its necessities and succeeded … in maintaining a regional unity in national politics to defend those necessities” (V. O. Key, Jr., Southern Politics, New York, 1949, p. 9).

Since the inciting element in the antagonism must be discovered in the business activities and conspiratorial planning of this powerful group, which sometimes take the form of related secret organizations, it is perhaps impossible for the ordinary social researcher to uncover all the pertinent data. Doubtless only Congressional investigations with their formal authority to compel testimony on the nature of the network of local and interstate economic, political, and even religious interests behind racial tensions would be reasonably sufficient. In 1948, when civil rights became a major issue in the presidential campaign, Thomas L. Stokes, the noted journalist, made this observation:

More and more people in the South are waking up to a truth which many have known for a long time. It is that the racial issue is capitalized by the demagogic type of Southern politician for his own purposes and for the purposes of the interests which, in turn, use him …. The [the politicians] appeal to the prejudices of many whites in the lower economic levels, because those unfortunate people fear encroachment in their limited field of opportunity. Racial prejudice is nurtured by economics. (Atlanta Constitution, Feb. 5, 1948)

Posture of Organized Labor

A further indication of the fact that the tender spots of typically Southern attitudes lie at the convergence of the races on the workers’ level is the spontaneous reaction which any labor organization entering the South to unionize the masses must expect. When, in 1946, the CIO decided upon such a campaign, the Ku Klux Klan was forthwith revived and the full machinery of employer resistance came into play. As an initial answer to the movement the Southern States Industrial Council, a business men’s organization, declared:

At last the plan and purpose of the CIO-PAC to establish political control over the nation and to supplant our democratic institutions … is in the open. If there has been any doubt about the aims of this organization, or the objects it seeks to attain, that doubt is dispelled by the announcements that the South is to be “organized” …. One of the most pitiful, and at the same time most dangerous features of this drive to organize the South is the way Negroes are being misled and used …. By advocating a system of social and economic equality … these people are promising the Negro an earthly Utopia …. The situation now is not unlike that which obtained when that “great democrat,” Thaddeus Stevens, attempted to enslave the people of the South and to confiscate their property …. I predict that the ones who will suffer most from the abortive efforts of this group … will be the Negro …. He will have no friends among his own race, and certainly he will have none among the Whites …. Like David of old, we … will continue to fight … to preserve our democratic institutions, our free enterprise system, and the Constitutional right of the American worker to be free. (Southern States Industrial Council, The Kiss of Death, Nashville, Apr. 29, 1946)

We have quoted at length from this statement for it represents an abiding attitude of the Southern economic leadership: its determination to combat organized labor; its recognition that the unionization of Negroes is a prospect most dangerous to its own monopolization of power; its suggestion of what inflammatory uses might be made of the “social-and-economic” equality issue; and its certainty that it can inflict such decisive punishment upon colored workers for entering the labor movement that they will not only “suffer most” but also be driven into still greater isolation. The CIO was thus confronted with formidable barriers; and these were the more effective because in that area the legislature, the courts, and the police are closely bound to the purposes and interests of the employing class. Indeed, they ordinarily tend to speak with one indistinguishable voice. By mid-1948 the leaders of the drive reported that they were meeting all the obstacles that “the well organized manufacturers’ organizations” could devise. “Management,” they said, “with years of experience in fighting unions in the North, has hired renegade preachers to preach that unionization is anti-religious. They have cooperated with the Ku Klux Klan to spread word that unions are un-American. Terrorism, brutality, race intolerance, and bigotry have had to be met and overcome” (Ed Stone, “Saga of Two Years in Dixie,” The CIO News, June 7, 1948, p. 6).

]]>The extraordinarily rapid ascent of Polish-born American-based Jan Lubicz-Nycz (1925–2011) and his equally precipitous descent into oblivion falls squarely into this singular dynamic. His remarkable story is a paradigmatic example of an individual capable of conceiving radical as well as factual solutions to real problems, whose revolutionary content, however, was significantly ahead of his time to the point of neutralizing the possibility of its actualization in the real world. The post-war society he designed for awarded his highly ingenious visions with prestigious recognitions and monetary prizes yet deprived him of the opportunity to see his schemes ever realized.

The central concern of all Lubicz-Nycz’s output was the conviction that architecture, taught, narrated, and practiced as an activity devoted to the conception and execution of singular projects of canonical import, failed to address in a substantive way the fundamental interconnectivity of all the components shaping the built environment. He detected an impoverishment of the urban fabric following the epochal changes the Industrial Revolution brought about in the modern city. The shift of focus from a unified conception of settlements, already present in Western and Non-Western traditions belonging to the pre-industrial past, had given way to a much narrower concentration on the single architectural object. Such a stance bestowed on a building alone disproportionate importance as an agent of influence for the vital functioning of its surroundings at a structural level. For Lubicz-Nycz, this was a fatal mistake directly attributable to the process of modernization, a collective error of judgment whose toll was manifested in the qualitative decline of the built environment of the twentieth century. Reacting to such conviction, he made the urban habitat the target of his design thinking. The schemes that he entered in the numerous international competitions earning him top awards were rooted in a new notion of space, which he labeled urbatecture. He wrote:

… the design process transcends the scope of architecture or urban design and transforms itself into an art or skill that I will call “urbatecture”. The realm of this art is the creation of an environmental concepts of an urban habitat, not in terms of separate building, but in terms of a harmonious scape, whether landscape, seascape or airscape, making its edifices out of

concrete and brick

trees and asphalt

glass and flowers

crowds of people

sounds of birds and foghorns

textures and colors

snow and winds

rising and setting sun

fusing all these into new forms of human habitat.1

Formulated during the sixties, when system thinking was occupying much of the architectural debate, this point of arrival in his intellectual development was rooted in his formative years in Europe.

In 1944, Lubicz-Nycz participated in the Warsaw uprising and after its fall became a prisoner of war in Germany. Following the liberation by the British Army, in 1946 he enrolled in a five-year program at the Polish University College School of Architecture in London, earning a diploma with a thesis on hospital design. From 1951 to 1958, he gained practical experience in four different firms working on a variety of project types at various scales. Also in 1958, he was registered as an architect and became an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Already at this early stage of his career, he invested significant effort in entering competitions structured around ambitious program briefs invariably connected to the larger question of the quality of the public realm. His 1957 entry to the Enrico Fermi Memorial Competition was a notable case in point.

At the beginning of 1959, he moved to San Francisco, working for six months each in the firm Stone, Marraccini, Patterson and in the office of John S. Bolles. He opened his solo practice in 1960 and entered a string of contests whose results catapulted him from unknown young designer to the limelight of the national and international stage. Lubicz-Nycz’s propositions emerged in the climate of collective interests in megastructures—that is, large-scale interventions in the city that merged the infrastructural layer of city living with the residential demands of communities increasing in density. Over the years, he developed a sequence of remarkable plans for rather large sites, each time offering an environmental totality responding thoroughly to both program requirements and the symbolic demands of the post-war age hungry for a cogent environmental identity.

It was the entry for the Golden Gateway in San Francisco, designed with John Collier and Philip Langley, that first put Lubicz-Nycz on the media map. His scheme, one of eight highlighted in the press, was deemed by Minoru Yamasaki in the expert panel “a daring and imaginative solution.”2 Following Lubicz-Nycz’s presentation of his project, Louis I. Kahn, also a member of the expert panel, reacted: “A very provocative design that would have an immense influence in the architectural world.”3 Kahn added: “He has devised a unit from which growth outward can develop.”4 Together with a shopping center, a bowling alley, and a recreation center, the scheme featured twelve apartment blocks, amounting to 2,135 units all endowed with a balcony, arranged according to a cruciform plan. Their silhouettes, conjuring a futuristic skyline, were profoundly advanced for the time and anticipatory of much later developments in high-rise design as well as in land management. Stacking took a curiously organic turn in the Polish émigré’s hands. Sloping terraced towers with narrower floorplates as they rise in height became the hallmark of a design vocabulary never seen before. Kahn further commented on his entry: “… you never know what beautiful and satisfying building will be like until a man with his [Lubicz-Nycz] make-up comes along and makes you know what it is.”5

That same year, he entered another competition for the design of the Liverpool Cathedral in England in association with architect Mario Ciampi, whose school projects in Daly City had given him nationwide exposure. While their entry failed to receive any awards due to insufficient information on the drawings, it was still lauded for the imaginative qualities illustrated. From a one-story modular podium, a gigantic roof structure of gothic vertical proportions spiked up to create the dominant image of this landmark. Although Lubicz-Nycz abandoned the Cartesian geometry in sub-subsequent projects, he did put forward a grandiose formal ambition of portentous undertaking calibrated to jumpstart a new spatial culture wherever he intervened. From his early works, the belief that the deep investigation of form was a pre-requisite for an architecture of historical identity within the genealogy of modernity was the constant of all his architecture.

The clamor the Golden Gateway scheme provoked in the local community provided the impetus for the talented designer to enter more competitions in partnership with already established local figures. Still with Mario Ciampi, and two other architects, Lubicz-Nycz submitted an entry to the 1961 competition for the Red Rock Hill Housing, Diamond Heights in San Francisco. His scheme was awarded first prize, an honor shared with three other teams, under the auspices of an Architectural Advisory Panel composed of John Carl Warnecke and Ernest J. Kump, among others. The bold concept comprising 990 units allocated in seven free form high-rise towers yielded “organic unity” in the jury’s praise, acknowledging its constructive efficiency and impressive monumentality as well. Leveraging the distinct topography of the site located in a prominent position within the San Francisco Bay, the team designed an ascent of levels of space-age flavor. Landscape, architecture, and infrastructure merged into one spatial continuum of noteworthy impact even for the era of utopian dreaming.

The following year, together with Robert Marquis and Claude Stoller, younger brother of legendary architecture photographer Ezra Stoller, Lubicz-Nycz entered a scheme to the Ruberoid/Matico Urban Renewal Competition for 5,000 dwellings, receiving a National Merit Award. The jury applauded the proposal for the ingenious sculptural skyline the six high-rise Y-towers generated as they grew out of the ground. The membrane-like quality of these structures and the formal handling of the terrain captivated the attention of the architectural circles. This novel approach, a sort of landscape urbanism of sizable dimensions displaying biological geometries, was utterly unprecedented even for the frontier ethos shared among the protagonists of the late phase of California Modernism. Yet, despite its groundbreaking content, there was a remarkable degree of engineering credibility in this project. The vertical thrust of his skyscrapers, a hallmark of his urban visions, would find tectonic resolution in the receding floorplates as the superstructure rose, attending even to the imperative of the real estate marketplace with the upper units available at higher prices than those below for the unobstructed views. Testing the mix-use development on sites as diverse in character as the cities where these ideas would be applied was the common thread of Lubicz-Nycz’s design contribution to architectural discourse. The concept was the same elaborated in many different versions: a tissue of buildings rather than an atomized sequence of individual structures disconnected from each other. This spatial continuum hosts the enmeshment of all living functions, a biological mix-use development of sorts: one large organism—literally an architecture of the size of a city—contains the richness of contemporary life as it happens.

Another leap forward in architectural stardom was the second prize his competition entry received for the redevelopment of the central area (Jaffa) in Tel Aviv, Israel, of 1963. Louis Kahn, who was once again a jury member in this new contest, praised this project, done with Donald P. Rey as a consultant. The brief required a radical idea to connect the historical urban pattern of Jaffa with the new city of Tel Aviv, operating on a large portion of the metropolitan area destroyed during the 1948 war. In this grand town planning exercise, the architect organized along a vehicular axis a large residential grouping of varying types: towers, randomly distributed low-height living blocks, and a pair of symmetrically laid crescents, all served by a level of parking of territorial scale. The result was a heroic sight conjuring images of fluidity, velocity, and modernity.

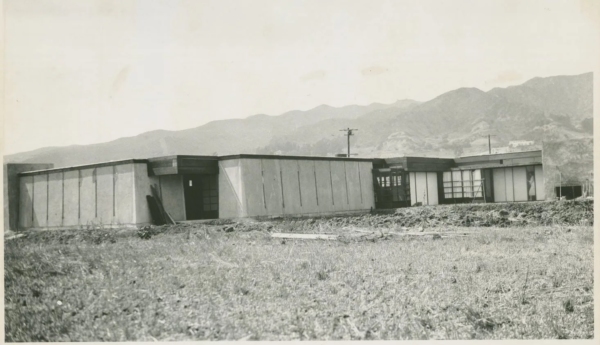

It was in 1964 that the first built accomplishment demonstrated in physical form the true talent of Lubicz-Nycz. Although the architect of record was John Bolles, the actual scheme for the McGraw-Hill West Coast Distribution Center was by Lubcz-Nycz. It was designed in 1964 and completed in 1966 in Novato, conspicuously visible from Highway 101. The compound, still standing, is comprised primarily of a 130,000 sq.ft. warehouse with a small office building and a cafeteria. The distinguishing features of the project were the hyperbolic paraboloid concrete shells with a 62-foot span forming the undulated roof. Admired to this day, this essay in concrete technology, designed with noted structural engineer Raj Desai, gave a hint of the uncommon capabilities that would single out Lubicz-Nycz from peers of his generation.

In the wake of such a winning streak in international competitions, the Italian architectural historians and critics—both Jewish incidentally, as the architect was—Bruno Zevi and Manfredo Tafuri took notice of his work. Zevi published repeatedly the architect’s projects and ideas throughout the 1960s in the magazine L’Architettura. Cronache e Storia.6 In an in-depth article that appeared in Casabella, Tafuri read Lubicz-Nycz’s proposal for Tel-Aviv as a mix between “surrealismo urbano di sapore avveniristico” (urban surrealism of futuristic flavor) and “tensione espressionista” (expressionistic tension).7 Furthermore, he detected the clashing of a novel morphology for the city, while at the same time trying to recapture the texture of the existing city—an insight virtually applicable to all the competition entries the architect would fashion through the decade.

Despite the enthusiastic endorsement of the most acclaimed architects of his time and the press around the world, none of his competition-winning entries were ever built. Already in the mid-1960s, the architect’s bitterness was mounting. Realizing that despite the glory, no prospect of getting actual contracts to build his projects was on the horizon, Lubicz-Nycz’s sour taste was palpable. “I have reached the critical point,” he is quoted.8 Disappointment notwithstanding, he continued to enter competitions. He earned first prize in the international competition for Hotel/Apartments/Commercial complex, San Sebastian, Spain (1964–66). His entry for the international competition for the redevelopment of the central area of Varna, Bulgaria (1967), was purchased by the client that promoted the context. He submitted an entry for the design of an International Headquarters and Conference Center, Vienna (1969). He was invited by the Principality of Monaco to participate in a limited architectural competition (1969).

To supplement his intermittent income as he continued his attempt to turn the tide with competitions, the architect started teaching architectural design at various universities across the country: UC Berkeley (1961–63), University of Virginia (1964–66), M.I.T. (1966–69), California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo (1970–73). He received his California license to practice architecture on October 17, 1967 (and let it expire on May 31, 2001), but following his latest teaching appointment, his work history appeared scattered. He collaborated for three years with Mario Ciampi (1973–76) working on urban and architectural projects, none of which were built. He later moved to Los Angeles, working for a year or two as a project designer for various firms, to then return to San Francisco in 1983. Although he continued to occasionally submit proposals to open competitions (Les Halles, Paris, 1979, and Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts, New Delhi, India, 1986), he progressively and quietly disappeared from the scene.

The precipitous plunge of Jan Lubicz-Nycz is an astounding case study in architectural history. This individual of universally acknowledged talent, featured in history books, hailed as the new promise in the development of a new, and more adequate, vision of the city was totally disposed of from the very system of professions that had initially welcomed him. His gradual fading from criticism is equally astonishing, especially at present, since a great many current urban visions and architectural fantasies propose the same identical formal world that this maverick had proposed sixty years prior. This twentieth century Piranesi, forced by circumstances to see his design dreams remain on paper, is a stark reminder of the contingent nature of the construction of historical memory in architecture, a process imbued with a complexity of human dynamics proportionally similar to the vast problems Lubicz-Nycz’s projects were attempting to tackle and resolve.

Notes

Over time, I became adept at reading Weber’s scrawled handwriting—it was equally difficult whether he was writing in English or German—and at identifying his realized buildings and projects. One afternoon, however, I pulled a photograph out of a small suitcase from one of the bedroom closets, an image of a work I had not seen before (fig. 1). It was a tiny structure, mostly open, with a pitched roof and what appeared to be drawers on the lower portion, which opened to one side. Two little girls were seated before it, each holding a doll. Nothing was written on the back.

I took the photo to Erika, who was out pruning in her rose garden, and asked her what it was. She identified the two girls as her sister Ursula and herself (left and right, respectively). The structure, she explained, was the “Seed Shrine.” Weber had designed it for his wife, also named Erika, an avid gardener, after he had moved the family from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara in the early 1930s.

With the onset of the Great Depression, Weber, like most of the Southern California modernists, was having difficulty turning up new—or any—commissions. In those days, the cost of living in Santa Barbara was markedly lower than in the city; Weber made the move to save money. Erika and the four children lived in a small, wooden clapboard house on Alamar Avenue; he lived and worked in Los Angeles during the week, sometimes sleeping in his office or on a couch at a friend’s apartment. Each weekend, he would commute home. Erika (the wife) was growing much of the family’s food; she asked him to build a workstation where she could sort and save vegetable and flower seeds. The drawers, each of which had a fine mesh bottom, were used to dry the seeds.1

Weber, I guessed, had taken the structure’s form from Japanese Shinto shrines, likely the type one might find on a roadside. For some time, I looked for sources but found no direct ones. Recently, I shared the photograph with Daichi Shigemoto, one of my doctoral students, who is working on the history of modern Japanese architecture. His response was that the Seed Shrine’s flat working surface, with the cacti and flowers, and the drawers below suggested something else: Japanese Buddhist funerary monuments.2 It seems that Weber must have drawn inspiration from various traditional forms and adapted them to his purposes.

But this raises a rather interesting question. There are few, if any, other direct Asian borrowings in Weber’s designs. Born and educated in Berlin, he was a notably (better, resolutely) German architect and designer, and to the extent that he derived forms from others, it was invariably from contemporary German modernists—above all, his beloved teacher Bruno Paul.

I have pondered this issue for a long time. Why, at this moment of crisis in Weber’s life and career, when he sometimes had to borrow a few dollars from friends just so he could put gas in his car or have a cheap meal, was he ruminating on Japanese architectural forms?

There is a larger question here, of course. It has to do with the symbiosis between East Asian forms and the rise of California Modern. Evidence of this influence of Asian design is everywhere: most of the leading Southern California modernists at one time or another made veiled or direct recourse to Japanese or Chinese tradition (more often the former); it is distinctly infused into a great deal of the new architecture.

Part of the answer as to why this happened is obvious: there was the extensive Pan-Pacific exchange of that time; the fact that there were many trading companies in California dealing directly with Japan and China; the cultural impact of the largish populations of Chinese and Japanese immigrants in the region; and the reality that Japanese architecture—especially—was admired by Western modernist architects.

There are, of course, various ways to get at this historical phenomenon. One could make a survey of the written or published influences, books like Ralph Adams Cram’s Impressions of Japanese Architecture, first published in 1905.3 One might also pursue other sources, from travel diaries and photographs to the then-popular penchant for collecting Asian antiquities. And one might also comb through the archives of the California modernists themselves, looking for direct, written clues.

The question I want to pose in this essay involves the specific role that this amalgam of Asian influences and modernist ideas had in forming the distinctive language of progressive California design. A definitive answer or even a topographic list is not possible here; that would require a far more extensive study—a book, really. Instead, I want to suggest a few corridors of seeing and understanding in the form of three short case studies.

1. M. Schindler’s Kings Road House

In one of the action scenes from Buster Keaton’s 1924 silent comedy film, Sherlock Jr., Keaton speeds on his motorcycle up a mostly empty Kings Road in Hollywood (fig. 2). Visible to the left, past several unbuilt lots, is R. M. Schindler’s 1922 house, one of the landmarks of early Southern California modernism. In this view—and even in the early images in the Schindler archive—the house at first appears fortress-like, with seemingly heavy battered walls and a few narrow slits for openings (fig. 3). But anyone who knows the house is aware that the impression from the inside—especially in the rear-facing unit (there were two, one for Schindler and his wife Pauline, the other for Clyde and Marian Chace)—is light, bright, and rather more “impermanent” in feel. Much of the structure is wood, with open ceiling joists, simple slatted walls, modular (rectangular) windows, and sliding doors. Some of the house’s formal language is lifted straight from Otto Wagner’s “school” at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts (where Schindler had studied before leaving for the United States). But more of it is decidedly Japanese in appearance.

Some of the likely sources for Schindler’s interest in the traditional Japanese house are obvious: the popularity of Japonisme in fin-de-siècle Vienna and his time working for Wright at Taliesin and, later, in Los Angeles, just at the moment when Wright was engaged with the Imperial Hotel Project in Tokyo. A team of Spanish scholars, led by José Manuel Almodóvar Melendo, have pointed to Schindler’s relationship with Arata Endo, whom Wright had hired to serve as “chief draftsman for the Imperial Hotel Project and during his one-year stay in Taliesin (1917–1918) … worked with the team responsible for transforming Wright’s sketches into working plans for the Imperial Hotel and into drawings for five Japanese residences and a theatre.” Schindler met Endo during this period, and the two maintained a long friendship.4 Still, much of the evidence they cite for Schindler’s connections to Japanese architecture and architects comes after 1922, after the house was finished. They also speculate about whether Schindler had seen Edward Morse’s 1886 book, Japanese Homes and their Surroundings, which is a likely source for elements of Wright’s Prairie house aesthetic.5

Morse, one of the first Westerners to document Japanese domestic design in detail, spent three years in Japan studying and teaching zoology. His book, which he published after his return, features numerous drawings he made of Japanese houses, including construction details—a great deal of what one would need to build in the same way. There is no evidence that Schindler knew the work. But it makes little difference whether he did or not. Somewhere along the path of his early career, he had seen enough of traditional Japanese building to borrow from it and transform it in his own way.6

I emphasize this because Schindler’s Kings Road House, one of the most manifestly Japanese of the Asian-inspired houses of the early Los Angeles moderns, was no mere replica. As Almodóvar and his co-authors note, Schindler implemented a composite construction system. Their claim is that it is “clearly similar to that described by Morse,” but, of course, that does not necessarily mean that Morse was Schindler’s source.7

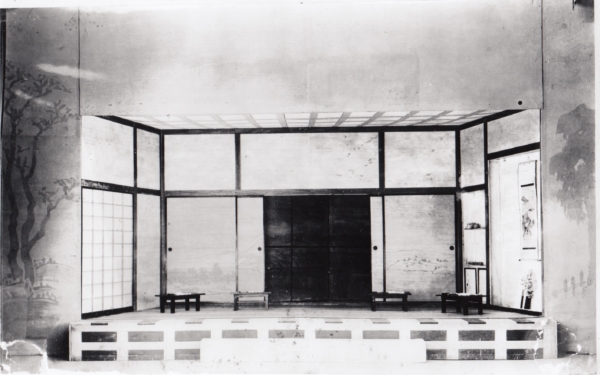

What one does see throughout the house is how Schindler adapted traditional Japanese woodwork to simpler joinery—mostly nails—and standard, industrially produced milled lumber (fig. 4). What is also evident is the way in which he opts for an open framing system, with spatial partitions arranged in such a manner that they are not load bearing—in keeping with Japanese tradition. In an article he published more than a decade later in T-Square, Schindler describes his approach: “all partitions and patio walls are non-supporting screens composed of a wooden skeleton filled in with glass or with removable canvas panels.”8

Schindler also followed the standard Japanese practice of leaving the materials—redwood, canvas, and glass—in their natural state, in no way embellishing them. Many of the other features of the house speak to traditional Japanese house forms—the imposition of multi-functional spaces, for example, or direct openings to the gardens, the use of screens in place of walls, and broad overhangs. There is also the house’s general sense of openness and the clear tensions between its geometric formality and the relaxed character of its rooms.

But it is not a Japanese house, any more than it is a Wrightian or a Wagnerian one. The overriding theme is Schindler’s attempt to devise a simple and light constructive fabric that could facilitate indoor-outdoor living, push new ideas of building logic (the lift-slab panels, above all), while granting the whole a decidedly modern cast. The Japanese element is a means to an end; it is not the aim. This becomes even more evident in Schindler’s subsequent house designs, beginning with the 1925 Howe House, which retain some of the spirit of Japanese construction while moving away from its specific forms. As Schindler came more and more to contrive his own distinctive architectonic language in the later 1920s, all that remained were a few abstracted bits of Japanese building logic. He adapted the Japanese forms not because he was seeking some type of verisimilitude—he was, in other words, not attempting to recreate a specific form-language in the mode of the historicists—but because he found the forms useful in his effort to devise an architectonic language suitable for the distinctive terrain and climate of Southern California.

2. Harwell Hamilton Harris’s Fellowship Park House

We can witness a similar process at work in one of the early designs of Harwell Hamilton Harris. Harris apprenticed with Richard Neutra in the late 1920s and early 1930s; he also learned informally from Schindler. He overlapped with Gregory Ain in Neutra’s office, and for a time the two assisted each other after they set out as independent architects.

In 1935, with his future wife Jean Murray Bangs, Harris bought a steeply sloping lot in the Fellowship Park neighborhood of Los Angeles. Soon afterward, he received a call from his client, Pauline Lowe (for whom he had designed a house in Altadena in 1933–1934), asking him to replace the Japanese sliding doors from her house, which she complained “rattled in the wind,” and install conventional hinged doors. Harris bought the sliding doors from the contractor for a dollar each and moved them to the lot in Fellowship Park.

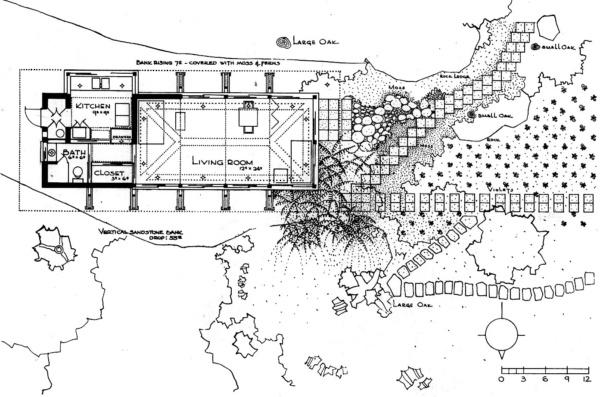

Harris stored the doors in a small shed on site, but he soon noticed that they were beginning to warp. He knew he needed to act quickly, lest the doors become entirely unusable, so he removed the shed and built a rectangular platform on wooden columns extending out over the hillside. In the living room of the structure, which occupied fully two-thirds of it, Harris installed the sliding doors, inserting them into a modular frame. When he ran out of doors, he made a solid section that helped brace the structure. The resulting dwelling was little more than the frame, a hipped roof, and the sliding doors (fig. 5).9

Harris asked noted local photographer Fred R. Dapprich to make images of the house while it was still mostly empty (fig. 6). He submitted the project to the 1936 House Beautiful Small House Competition. It won first prize, beating out two houses designed by Neutra. In 1938, it received an honor award from the Southern California chapter of the American Institute of Architects.10

What Harris later said about the design underscores my thesis. He did not opt for Japanese forms because he sought to imitate them, he explained, but because they allowed him to explore an issue arising from the unique conditions of living in the region and his own formal predilections: “The Japanese house most satisfied my liking for immaterial form,—for space. It did not displace space; it marked space, it shaped space. And the materials of Japanese building—hardly more than thin lines and flat planes—were arranged to effect rhythm, rhythm without mass.”11

One could add that the mostly open house, very lightly constructed, was ideal for Southern California living. The house became fused with nature. It was man-made but entirely natural in terms of its materials and fully “connected” with its surroundings. Lisa Germany, who wrote the standard monograph on Harris, reveals that he “planted asparagus fern and mint he got from an aunt” around the house. “I would hose it off,” he recalled, “and so fill the air with mint odor (very fresh).”12

In his subsequent works, Harris would often reference Japanese forms—in the 1939 Blair House, for example—employing screens, a penchant for natural materials, and a pronounced formal modularity. What stands out even more is his interest in the play of light, which to my eye often has about it a Japanese sensibility. Harris was sensitive to fostering light patterns—or better, maybe, oppositions between light and dark, a long view and a truncated one, and the notion of pure subdued light versus shadow and patterning—all present, for example, in classic Japanese tea houses. Many of these mannerisms remained in his work, even in his later periods in Austin and Raleigh, where he spent his final years.

But Harris’s process was always about refinement and purification, about extracting effects from the forms rather than any sort of direct referencing. None of his later works appear directly Asian or Asian-inspired; they are instead the outcome of thinking about what Japanese traditions might yield in modernist terms.

3. Edward Durell Stone and Paul T. Frankl’s Coldwater Canyon House

Of the early Los Angeles moderns, the one who had the most direct contact with Asia was Paul T. Frankl. Frankl visited Japan twice, once in 1914 and again in 1936. He also made a hasty buying trip to China in 1939.13 Far more than Schindler or Harris, Frankl also made a concerted effort to learn about Japanese design philosophy. During his first sojourn in Japan, which took him to Tokyo (he stayed in a traditional inn, not far from the future site of Wright’s Imperial Hotel), then on to Nara, Osaka, and Kyoto, he was careful to observe all he could. And while in Kyoto, he had lessons in Japanese flower arranging, a skill he would use for the remainder of his career.

During his time in Japan, Frankl made note of even the most trivial details of living. He wrote of the “refinement” and “dignity” he saw everywhere; he was especially struck by the “art of elimination,” which he thought posed a potent alternative to Western taste. He described it as “the distilled essence of beauty.” And he took away from his experiences an especially strong love for the Japanese “simplicity of expression” and the “ability to use materials true to their nature.”14

In his later autobiography, he wrote about his love of traditional Japanese dwelling spaces: “The Japanese house always made me feel good and living in it takes me back to my early childhood in the nursery, where life was lived on the floor. The scrupulously clean, resilient tatami mats covering the floors … are pleasant to the touch. Seated on them or on a soft, comfortable silk pillow, you have the feeling of space and elbow room.”15

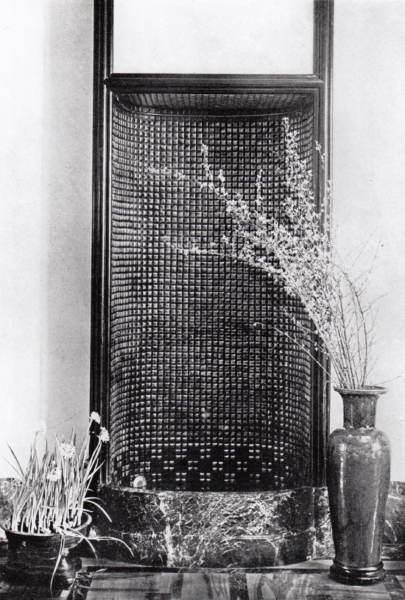

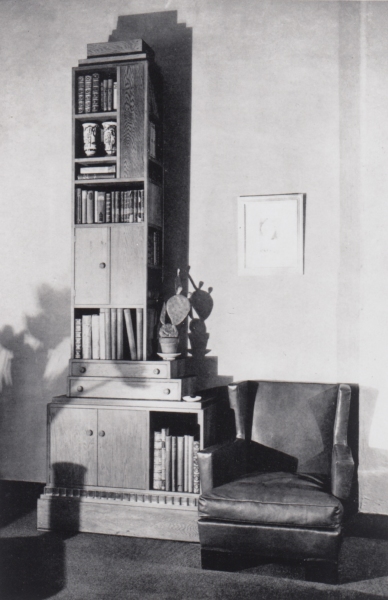

When Frankl first began to practice in New York in 1915 (he was unable to return to Vienna because of the outbreak of the First World War), he sometimes made distinctly Japanese references in his designs (fig. 7). And he recreated—quite faithfully given the circumstances—a Japanese interior for the play Bushido by Takeda Izumo, which was produced by the Washington Square Players at the Bandbox Theatre in New York in 1916 (fig. 8).16 Frankl’s later Skyscraper bookcases and desks, which catapulted him to fame in the mid-1920s, were based in part on Japanese Sendai chests, which he came to appreciate during his first Japan trip (fig. 9). Later, in his Los Angeles gallery, Frankl sold patio lounge chairs that seemingly borrowed their forms from the bridges in Chinese gardens (fig. 10).

It is hardly a surprise then that when Frankl decided to build his own house in Beverly Hills, he opted for a quasi-Asian “palette.” Frankl, who did not have an American architect’s license, asked Edward Durell Stone to design the house; Frankl would devise the interiors. Stone, who was not licensed in California, in turn worked with local architect Douglas Honnold.17 The house they created drew directly—or so it seemed—from traditional Japanese farmhouses, notably those with low, hip-and-gable roofs (fig. 11).

Frankl, however, explained that part of the house’s appearance was determined by the site, a long, narrow lot framed on one side by a stand of old walnut trees and on the other by the canyon walls. The rooms were arrayed in a nearly straight line, stair-stepped in two places to accommodate the sharply sloping terrain. An unnamed writer for California Arts and Architecture added that the house was “conceived in the modern spirit and kept simple and straightforward by the elimination of all things directly not necessary to the mode of life chosen by the owners.”18

The house was thus, at best, Japanese “inspired.” The interiors bore this out. Frankl made a lovely interior garden arrangement by one of the stairways, lit from an exterior window (fig. 12). It appears to be much in the spirit of a Japanese formal garden—until one makes the direct comparison. Then the differences emerge. It is too condensed with too many elements. It is rather more an interpretation or an adaptation than an attempt at mimicry. The same may be said for the living room, with its pseudo-Japanese flower arrangements (fig. 13). But they are very nearly inconsequential. The cast of the room is Central European, almost Loosian with its changes in level and the deep, vaguely historically inspired veil of comfort. No one with any familiarity with Japanese design would mistake this space for a traditional house in Kyoto. And any good design historian in Vienna would recognize many, if not almost all, of its features.

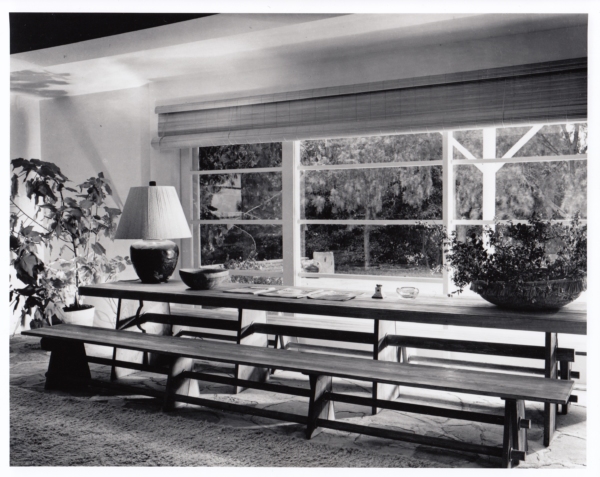

What Frankl excelled at instead was a clever sort of reworking. He would borrow elements—ofttimes, the essential features of a design—and through thoughtful fusion spawn something new—or almost new. My favorite example is the table and benches he made for the dining room of his house in Palos Verdes, where he moved his family after the American entry into World War II (theorizing that the Japanese were less likely to bomb that far away from Los Angeles proper). They are sandblasted ash with the grain left in high relief—and in that sense wonderfully Japanese in their material sensibilities (fig. 14). But the set is also something quite familiar—an adapted American picnic table, though exquisitely remade with X-supports and long, continuous dowels. It is straightforward, even spartan, but elegant and perfect in its simplicity.

Most of all, like the other examples I have discussed, the table and benches were—to borrow a familiar musical term—a riff on the originals. And to extend this metaphor, in each instance their makers were extracting a few bars from another tune, all the while singing their own song. Los Angeles modernism was never exactly “influenced by” Asian design so much as its makers mined bits and pieces and recast them. The essential features (mostly Japanese, again) are all there—space, light, thinness, lightness, and transparency, with a strong penchant for interacting directly with nature. But they are “re-shaped,” made new and original.

One might ask whether California Modernism would have arisen as we know it without the influence of these Asian forms or concepts. It is, of course, an impossible question to answer. I suspect the closest we can get to the truth is that it was “necessary but not sufficient,” meaning that many other influences and ideas came to have a part in the rise of this distinctive aesthetic. There is certainly research to be done, and with far greater specificity than what I have laid out here.

A Final Note

Weber’s “Seed Shrine” had a brief afterlife. After several of his friends, including Lloyd Wright, admired the design, Weber thought about producing and selling it. He approached one of his old acquaintances, Theodore W. Overlach, who owned a garden accessories shop in San Francisco. Overlach, too, was taken with the design and drew up a contract, agreeing to pay Weber $5.00 for each unit he sold. A few evidently were made, but the “Seed Shrine” was never a bestseller.19 It was, like much else that referenced Asian design in California, a one-off.

Notes

In recent decades, as R. M. Schindler has belatedly assumed a position of eminence in modernist architectural history, attention has fallen on “Modern Architecture: A Program,” a manifesto-like essay that Schindler wrote in Vienna during his apprentice years. The essay’s significance is obvious, but its origins have remained somewhat obscure. Researches in the Schindler Papers at the University of California, Santa Barbara have allowed me to pinpoint the document’s gestation with some precision. What follows is a report on that research, together with a new translation of the Program, based on the original manuscript. Schindler’s far-sighted ideas about modern residential design remain the same, but their context has shifted and expanded.

The publishing history of the Program is tangled. The most familiar version is one that Schindler made in English sometime before 1932, when he sent it to Masakazu Koyama, the editor of the Japanese architectural magazine Kokusai Kenchiku, and also appended an excerpt to his short critique of functionalism in the Southwest Review. This rendering was included in the dossier of writings that Schindler gave to the architectural historian Esther McCoy, and it was subsequently published in books by David Gebhard, Judith Sheine, and others.1 Two other drafts, in German, can be found in the Schindler Papers. One, a typescript with corrections and additions, appears to date from the 1920s; in 1995, it was published in the catalogue for the Kunsthalle Wien exhibition Visionäre und Vertriebene (Visionaries and Exiles).2 There is also a set of handwritten pages, some of which carry the date 1913. Barbara Giella transcribed these for her 1987 thesis on Schindler’s work of the thirties; a translation followed in Lionel March and Judith Sheine’s RM Schindler: Composition and Construction.3

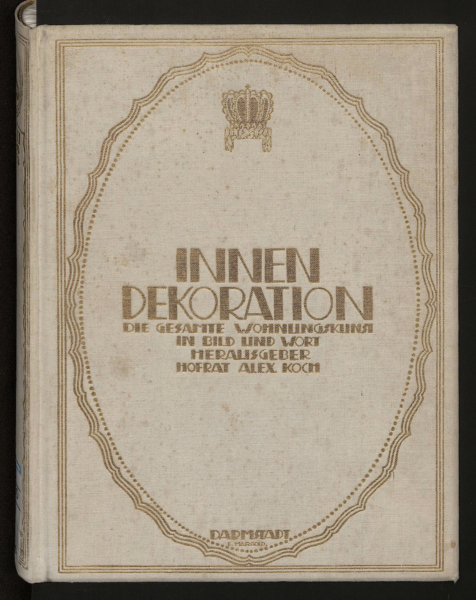

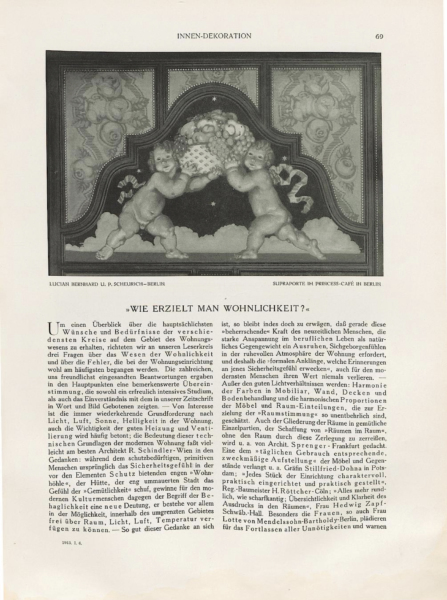

Analysis of the Program has been complicated by the fact that its various drafts are scattered through the Schindler archive. Two sheets of the handwritten manuscript, with writing on both sides, surface in a folder marked “Letters not sent.”4 Two other sheets, again with writing on both sides, show up amid Schindler’s correspondence with Neutra.5 Only the typescript version is filed in a folder identified with “Modern Architecture: A Program.” Furthermore, the challenges of reading Schindler’s German handwriting have hindered comprehension. Giella’s transcription presented two of the pages in the wrong order, resulting in several garbled passages.6 No one appears to have taken notice of a few lines on one page that specify the jumping-off point of the entire exercise: a questionnaire sent out by the Darmstadt-based journal Innen-Dekoration in January 1912 (fig. 1). I have concluded that Schindler’s Program took shape in response to that questionnaire.

At the time that Schindler made the notes that evolved into the Program, he was studying under Otto Wagner at the Akademie der bildenden Künste (Academy of Fine Arts), in Vienna. He was also attending private lectures by Adolf Loos, in the course of which he first encountered Richard Neutra. The use of the phrase “modern architecture” is, among other things, a nod in the direction of Wagner, who had published the first edition of his famous book of that title in 1896. Yet, as Harry Mallgrave has pointed out, the Program diverges in important respects from Wagner’s aesthetic, rejecting the older architect’s insistence of endowing constructive principles with expressive potential.7 Nor does it necessarily conform with Loos’s teachings circa 1912. It espouses something of a third way beyond Wagner’s beautified modernism and Loos’s reaction against the ornamented exterior.

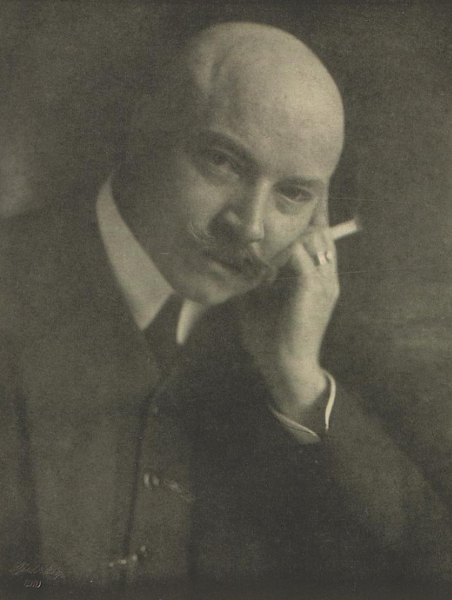

Alexander Koch, the editor of Innen-Dekoration and of the even more widely read Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, was a vigorous promoter of interior-design reform, his aesthetics closely aligned with those of the Jugendstil movement (fig. 2). Innen-Dekoration is best remembered for having held a design competition in 1901 for a theoretical house to be called Haus eines Kunstfreundes, or House for an Art Lover. The winning designs, by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Margaret Macdonald, Mackay Hugh Baillie Scott, and Leopold Bauer, offered pared-down, formally striking, internally fluid models for residential design, which gave inspiration to the rising generation of Austrian architects, Schindler included. Koch also drew notice for his role in and promotion of the Darmstadt Artists’ Colony. A Wagner student like Schindler would naturally have monitored Koch’s publications, even if, as Sigrid Randa-Campani observes in her study of the publisher, Koch had taken a somewhat conservative, backward-looking turn in the years after 1908.8

The January 1912 issue of Innen-Dekoration featured a questionnaire asking readers what they valued most in the concepts of “Wohnlichkeit” and “Behaglichkeit”—near-synonymous words that connote livability, comfortableness, coziness. The magazine addresses “three questions to all who have talent and sensitivity for Wohnlichkeit”:

- How do you imagine a comfortable home?

- What in your view are the main points that must be fulfilled in the achievement of comfort and well-being in the home?

- What in your opinion are the most common home-furnishing mistakes and how are they to be avoided?9

A summary of responses to the survey was printed a year later, in the January 1913 issue, apparently with the participation of the distinguished art historian Paul Westheim. The headline was “Wie erzielt man Wohnlichkeit?”—“How does one achieve comfortableness?” (fig. 3). Among the replies, the contribution of a young Viennese architect named R. Schindler was singled out for praise and summarized as follows:

While the feeling of “coziness” [Gemütlichkeit] originally created for protection-seeking primitive man a sense of security in the narrow “living cave” [Wohnhöhle], providing protection against the elements, in the hut, in the narrow-walled city, for modern civilized man the concept of comfort [Behaglichkeit] is interpreted anew: it consists above all in the possibility of being able to freely control space, light, air and temperature within the enclosed area.

The editor praises Schindler’s ideas but adds a qualification: sensations of comfort and security are no less crucial for modern people who might have mastered the elements but still require a restful atmosphere as a respite from the stresses of daily existence.10 Anyone who knows Schindler’s Program will have recognized some familiar formulations. One quoted phrase—“formalen Anklänge, welche Erinnerungen an jenes Sicherheitsgefühl erwecken,” or “formal echoes which awaken memories of that feeling of security”—appears almost word for word in the various versions of the Program.

The two sheets that can be found among “Letters not sent” in the Schindler Papers would appear to be a rough draft of the reply that Schindler submitted to Innen-Dekoration. The first sheet is marked February 1912 at the top; Schindler had obviously set to work shortly after reading the previous month’s issue. Schindler writes, “Reply to the general survey by the magazine Innen-Dekoration,” and names Hofrat Alex Koch as the addressee. He then copies out the three questions. What follows corresponds roughly to the final section of the published versions of the Program.

For the Urmensch [primitive man], the value of his cave lay in its hiddenness and narrowness—in the feeling of security which it gave to the occupant—The medieval city supplied the same sense of security through its building principle of crowding as many defenders as possible into the smallest perimeter—

The farmer feels comfortable only in a hut that answers his need for protection from the elements by way of the strongest contrast with the outer world—

For the majority, “gemütlich,” “comfortable” means spaces which can awaken memories of those feelings of security through formal echoes—

Civilized man progresses from flight before the elements to their domination—For him the home is no cowering hideout—through his power he has found the way to nature. The words “gemütlich” “comfortable” have a different ring—The comfort of the dwelling lies no longer in formal shaping—but in the possibility of freely governing time, space, light, air and temperature within its limits.

The dwelling will not wish to have style, personality, expression— will no longer bellow — like an eternal gramophone for every passing mood of the architect and owner — it will be silent and will provide a peaceful setting for the owner.11

When Innen-Dekoration gave a brief summary of Schindler’s commentary in its January 1913 issue, the architect may have been prompted to develop his thinking further. In any case, two further pages with writing on both sides are marked “June 1913.” Here again there is a discrepancy in Giella’s transcription. On the back of the first page was a section on the topic of monumentality in architecture. In the transcription, this has been moved after the material on the following sheet. Giella presumably did this because Schindler himself changed the order when he made his typewritten transcription and English translation. She also followed Schindler in placing the 1912 material last. For the purpose of documenting the first version of the Program, the earlier order should be retained. Incidentally, none of these early documents bear a title; “Modern Architecture: A Program” came later. Here is a translation:

The first living space was the cave.

The first house was the hollow heap of earth.

Building meant—gathering and piling up building material with room for air-living-spaces.

This viewpoint is the basis for understanding all architectural creations from the beginning of time up to the twentieth century A.D.

The goal of architectural striving was—formal subjugation of the mass of building material.

The idea came only from the sculpturally malleable mass of material.

The vaulted ceiling was not a spatial idea, instead it was a form for distributing material so that the mass was kept suspended.

Shaping the projection of the mass into space was the task of wall decoration.

The problem has been solved and is dead.

We—no longer have a sculpturally malleable mass of material.

The modern architect conceives the space and shapes it with wall and ceiling panels.

The idea comes only from the space and its elaboration.

Without the mass of building material, the negative of the space on the inner wall of the house appears unimpaired as a positive on the outside.

Hence the “box-shaped house” emerged as the primitive form of the new line of development.

A new problem has arisen—and, as ever, the concept of purpose guards its birth.

Monumentality is the expression of the memorial of a power.

The first ruler was the tyrant.

His power over the crowd found expression in the physical overcoming of static forces. In keeping with a primitive level of culture and sensitivity, the power-symbol was restricted to overcoming two of the simplest forces: heaviness and cohesion.

The monumental effect grew proportionally with the “work of material distribution” being brought to expression.

Man defers to the heft of the earth.

Today a different power of humanity demands its monument.

Spiritual creative power has broken the might of the physical tyrant.

Man has found a more mature symbol for the overcoming of physical forces—the machine.

The mathematical overcoming of the static renders it formally and artistically expressionless.

The new monumentality of space will adumbrate the infinite limits of the spirit. Man shudders in the vastness of the cosmos.

R June 1913

The first house had to give people protection.

The sense of security was heightened through every indication of the durability of the house.

To the architect, therefore, construction must have appeared to be the most effective means of expression.

All building styles up to the 20th century AD are “constructional.”

The quest to symbolize the constructional function of the mass of building material furnished ideas for form.

The last stage of this development is artistically conceived steel construction. In the steel frame, form is no longer a symbol of the constructional play of forces—construction has become form.

With the help of concrete building, the 20th century takes the first steps towards formally dispensing with construction.

The constructional problem has turned into a mathematical equation. The structural calculations filed with the city building authority render formal guarantees of safety superfluous. Construction has become devoid of interest.

Modern man no longer takes notice of the construction—the concrete pillar, the beam, the mass of the wall—because there is no longer a columnar form, architrave, wall plinth, crowning cornice—instead he sees the freedom of cantilever construction, the openness of the span, the space-defining surface of the 7-cm thick wall.

The house-building artist’s quest to use the form as a constructional symbol or to give the construction an artistically expressive form is dead.

There is no longer a constructional style.

The architect’s natural inclination to build constructionally has become a bogus buzzword in a day and age that wishes to give its artists the strangely necessary exhortation: Build with all spiritual and technical resources that your culture offers you.

R June 1913 12

What happens to our understanding of Schindler’s Program when its context is restored? First, it is all the more clear that, as Mallgrave argues, the young architect is distancing himself from—if not rejecting outright—prevailing values of the Jugendstil and Secession movements, not to mention central tenets of his teacher Otto Wagner. In Modern Architecture, the latter had written that “the architect must always develop the art-form out of construction.”13 Schindler, on the other hand, boldly announces that “there is no longer a constructional style.” Indeed, the very notion of construction-oriented building is a falsches Schlagwort.

Schindler comes closer in spirit to Loos, who had argued that architecture must transcend the expression of personality, of the mentality of a particular artist. Schindler also shows kinship to other radical trends in Viennese modernism. Although there is no sign that he paid heed in this period to Arnold Schoenberg—unlike Neutra, who knew the composer and attended his concerts—the idea of an architecture of space supplanting an architecture of form brings to mind Schoenberg’s desire for “complete liberation from all forms, from all symbols of cohesion and of logic,” his desire to dissolve musical architecture into a “vivid, uninterrupted succession of colors, rhythms, and moods.”14

At the same time, Schindler also declares a degree of independence from Loos. The question of ornament is not under consideration. Schindler’s ideal architecture does not have the air of being embattled against an establishment. The concept of a house that transcends the need to supply shelter and security does not exactly reflect the values of Loos, who, as Mallgrave notes, tends to make a sharp divide between exterior and interior. Loos said in his “Heimatkunst” lecture of 1912: “The house should be discreet on the outside, inside it reveals all of its richness.”15 In a certain sense, Schindler’s interest in transcending the relation between construction and form puts him in conflict with a classic modernist ideology that was still in the process of formation.16 As August Sarnitz comments, the idea of an interior connecting fluidly to the exterior harks back to the principles of the modern English house, which, we can add, had been celebrated in the pages of Innen-Dekoration.17

The new factor that has undoubtedly entered into Schindler’s thinking about construction and space is the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Wasmuth portfolio, which had galvanized Schindler as it had so many other young modernists. In his “Space Architecture” essay of 1934, Schindler recalled his first reaction to the Wasmuth portfolio: “Here was ‘space architecture.’ It was not any more the questions of moldings, caps and finials—here was space forms in meaningful shapes und relations. Here was the first architect.”18 Although Wright goes unnamed in the Program, he hovers behind the essay as a guiding spirit.

Once Schindler came to America, the ideas of his Program continued circulating through his writing and notes, even if his close-up encounters with the American built landscape caused him to make some adjustments. His impressions of New York and Chicago tended toward the negative: he experienced little of the ecstasy that had swept over Loos during his American sojourn in the 1890s. Manhattan struck Schindler as a city “arising from mass demand,” its population crowded into spaces where little natural light can penetrate.19 When, in 1917, he attained his long-sought goal of finding a position with Wright, more disappointment set in. The great man was unable to see Schindler as anything but a peon. There was also a philosophical difference: the architect of open space whom Schindler had admired in the pages of Wasmuth portfolio was going into partial eclipse, as Wright turned toward the hulking masses of his neo-Mayan style. What Judith Sheine describes as a “vocabulary of heavy forms decorated in a stylized motif” struck Schindler as a regression.20 In “Space Architecture,” he complains that Wright “tries to weave his buildings into the character of the locality through sculptural forms.”21

The move West brought more positive perspectives. Schindler had already visited Southern California and the Southwest in 1915—a trip that Albert Narath discusses at length in his 2008 essay, “Modernism in Mud.”22 In the winter of 1920–21, Schindler wrote to Neutra: “If I am to speak of ‘American architecture’—I must say at once that no such thing really yet exists … The only buildings that show true feeling for the earth that bears them are the old adobe buildings of the first settlers and their successors—Spanish and Mexican—in the southwestern part of the country.”23 A blunter assessment appears in Schindler’s notebooks from 1916: “The country is empty—except in the Pueblo domain.”24 After his first Southwestern trip, he designed an unbuilt house for the Taos physician Thomas Paul Martin, which he described as a “low stretched mass of adobe walls, with a rather severe expression for the outside.”25 This was intended to blend into the vastness of the landscape, although, as Narath points out, it retains a monumental weight.

The Program resurfaces in notes for lectures that Schindler gave at the Church School of Art in Chicago in 1916. One page is given over to a translation of a passage from the essay. Schindler’s English was still a work in progress, but the language has a distinctive flavor:

Monumentality—is the expression of a lasting symbol of a power

The first power-possessor was the—tyrant

Mankind gave expression to its awe for his power thru structures, the value of which consisted in the amount of labor spent for theyr construction.

A primitiv state of cultur is satisfied to express in its monuments the overcoming of two elementary forces only: gravity & cohasion

The monumental effect grows in proportion to the expressive: “transposition of matter”

Man worships the might of the earth

Different powers claim other symbols

The creative mentallity breaks the power of the tyrant

Mankind found its ripest symbol for the mastering of physical forces “the machine”

The mathematical solution of the problems of the statics destrois theyr artistic formal expressivenes

The new monumentality of the space will disclose the spiritual freedom of man

Mankind bows facing the unlimited firmament26

In German, the final line is “Der Mensch erschauert in der Weite des Weltalls”—almost Wagnerian in its alliteration. Schindler’s first English rendition has a different ring. It conveys the idea of a house open to the sky, the inhabitant bowing before it—a more quietly blissful scene. An excursion to Yosemite National Park seemed to transform Schindler into an echt-Californian. He wrote to Neutra in October 1921: “I camp on the bank of the Tenaya—sleep on a spruce-needle bed under the open sky and bathe in the ice-cold waterfall.”27

In all, the experience of the Western landscape encouraged Schindler to think more deeply about opening the interior to nature—a concept that is not explicitly articulated in the Program. The architect’s celebrated residence on Kings Road, which was completed in 1922, gives evidence of that shift. From certain vantage points, it presents a cement façade nearly as massive as the ones sketched for T. P. Martin. Yet, as the studios open onto the interior courtyards, they afford a seamless transition from inside to outside, with walls dematerializing into sliding partitions. The structure no longer provides a feeling of total security, as in the past architecture analyzed in the Program; adobe walls are more intimated than imitated. Monumentality has been left behind. The design plainly registers the impact of the proto-modernist Irving Gill, whom Schindler got to know on moving to Los Angeles. Gill’s increasingly abstract take on Spanish revival styles also entailed a lightening of masses, as white-walled buildings dissolve into surrounding foliage and ambient light.

The distance that Schindler has traveled from his Wagnerschule/Loosschule beginnings is manifest in his vituperative reaction to Loos’s 1919 compendium, Richtlinien für ein Kunstamt, or Guidelines for a Ministry of Art, a copy of which was apparently sent to him by Neutra. Against the background of the Social Democratic advance in the early postwar era, Loos and his collaborators called for close government supervision for the arts, equitable pay for artists, and a suppression of arbitrary individual artistic invention. Schindler, in a letter to Neutra, professed disbelief that his old mentor was responsible for the document. He was aghast at what he called a bailiff’s vocabulary—dürfen, müssen, sollen, verbieten (be allowed, must, should, forbid). He was particularly incensed by a section written by Schoenberg, in which the composer demanded measures to “ensure the German nation’s superiority in the field of music, a superiority rooted in the endowment of the Volk.” For Schindler, such nationalist sloganeering demonstrated an obliviousness to the actual wishes of the public. He declared the Richtlinien “tot und modern”—“modern” here connoting rot and decay, not progress and innovation.28

A fascinating note from 1925 shows Schindler searching out another kind of third way, this time in an international context. He distances himself both from the doctrinaire modernism that was taking hold in Europe and from the mass-produced real-estate industry of Southern California: “The European and the American way of reaching the top: the first has one—only one—idea —makes it a religion and becomes its god. The other imports an idea, becomes its sales manager and fortifies his position at the source with gold.”29 Such independence of spirit would be the hallmark of Schindler’s subsequent career, which spurned the strictures of the International Style while making no concessions to the marketplace.

To an astonishing degree, Schindler remained loyal to the principles he had set forth in the Program of his early years. To walk through the most remarkable instances of Space Architecture—the Kings Road house, the Lovell Beach House, the cluster of houses above Silver Lake Reservoir, and the Kallis House, to name a few—is to feel the aptness of Alexander Koch’s summary of the then unknown architect’s ideas: “The concept of comfort is interpreted anew: it consists above all in the possibility of being able to freely control space, light, air and temperature within the enclosed area.”

Notes

“Race and race difference alone can never adequately explain the status of the Negro in America. The Negro problem is something a good deal more significant than a mere ‘race’ problem; it is a problem which probes deeply into the historical development of the economic and political structure of the American society and runs parallel with it.” — Ralph J. Bunche, A Worldview of Race

Gunnar Myrdal’s An American Dilemma paved new ground for the study of race relations in the United States. While his work went on to influence policymakers and a supreme court decision and eventually drew the violent ire of Southern segregationists, significant dissenters on the left argued early on that the work was, at best, a liberal and reformist apologia for the ideological apparatus needed to uphold a capitalist society. One such critic was Trinidadian-born sociologist Oliver C. Cox, who had begun his assault on the “Caste School of Sociology” in the mid-1940s. Cox argued that Myrdal had mystified political-class relations as those of two discrete and antagonistic racial castes. Cox offered his rejoinder in a major critique found in his 1948 magnum opus, Caste, Class and Race. In America, he said, there was no such caste system; race relations were relations of unequal political-class power and grounded in the incentive structure of a highly developed capitalist society. Race relations, properly understood, were a reflection and the result of the necessary antagonisms between two political classes. Race prejudice first emerged out of the demands of a burgeoning capitalist society and was then fully expressed once that society had become the global imperialist core nation. The solution for race prejudice and exploitation was, therefore, part of the same political future: socialism, which must, he believed, overturn the methods of production and exploitation, eliminate the need for profit and competition, and dissolve the material requirements which undergird the production of race prejudice and racial hierarchy.

1. Gunnar Myrdal and the Caste School of Race Relations

From the moment the book was first published in January 1944 until the present day, there is perhaps no more influential nor more ambitious single work on race relations in the United States than Gunnar Myrdal’s monumental An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. The text, funded by the Carnegie Corporation and published in two enormous volumes, runs over one thousand pages of dense and frequently repetitious social science and economic analysis of race relations in the United States. Nevertheless, despite its mid-war publication and imposing length, conditions which could have lost the work to the annals of history, the study proved to have an immediate impact and enduring value for subsequent decades. The influence of the book culminated in 1954 when it was cited in support of the Brown v. Board of Education decision, a fact neither Myrdal nor the Carnegie Corporation itself (nor, indeed, opponents of the study, among them Southern reactionaries) would soon forget.1

As political scientist Michael C. Dawson has written, An American Dilemma is “still the seminal work on American race relations,” providing something of an unavoidable touchstone to scholars and activists, even if it is not (or no longer) followed as political doctrine, nor does it continue to exert the same popular influence it enjoyed some half-century ago.2 Nevertheless, while the influence of Myrdal’s study has waned with time, two factors remain of continued importance. First, the research group employed or consulted to produce An American Dilemma reads like a list of some of the greatest social scientists of the twentieth century, many recruited at the height of their powers. Among these extremely capable scholars were Ralph J. Bunche, W. E. B. Du Bois, E. Franklin Frazier, Abram L. Harris, Charles S. Johnson, Alain Locke, and St. Clair Drake. At least one researcher, Doxey Wilkerson, subsequently denounced Myrdal’s project as little more than liberal propaganda in his introduction to Herbert Aptheker’s critical polemic.3 The group itself is of great historical importance not only because it was perhaps the only time such a talented cohort of social scientists had taken part in a single study of American race relations, but because many were or would become influential in politics, the arts, and in academia. Missing among this group, of course, was Oliver C. Cox, a scholar still little known, just a few years out of graduate school, but who had already launched what would become a lifelong attack on the caste school of race relations, a school which he believed reached its apotheosis in the work of Myrdal.4

Second, and relatedly, Cox had firmly rejected the main caste apparatus espoused by Myrdal and many of his fellow researchers, including the most influential account by the University of Chicago sociologist Robert E. Park.5 Though he was not alone in this denunciation, he provided, to the present day, the most rigorous critique of race-as-caste sociology.6 He argued that placing caste (or race) at the absolute core of social life did not only fail to explain racial hierarchy, exploitation, domination, and the vast array of disparate life outcomes, but it was a form of mystification of material, economic relations. It pitted racial groupings against each other as natural and permanent antagonists. It suggested the replacement of material causation, grounded in the processes and compulsions of political economy, for eternal or nearly eternal ideal-type categories which deploy psychological, libidinal, or ideological explanations almost arbitrarily as the basic pseudo-causes of asocial group behavior and inequality based on ascriptive differences. Therefore, he thought, any social science that understood caste as that which not only describes real social division but posits it as a social and political essence would likely do far more harm than good and would never reach the real mechanisms that provide the conditions for the production, deployment, and the endurance of race prejudice. Witness, for instance, that Myrdal ultimately calls only for minor reforms, such as improved and equal educational opportunities. According to his theory, such reforms would encourage further reforms or alterations in other parts of the social network, eventually leading to a satisfactory change in relations in general terms. “[T]here is no ‘primary cause’ but everything is cause to everything else,” Myrdal argued. He believed this position was “bound to encourage the reformer” for whom “[t]he principle of cumulation—in so far as it holds true—promises final effects of greater magnitude than the efforts and costs of the reforms themselves.”7

On the other hand, Cox unequivocally advocated for the necessity of a class- (or perhaps better, labor-) based socialist revolution. Race-as-caste, race reductionism (to use Touré Reed’s recent phrase), or other common manifold formulations of homogeneous racial group interest therefore amount to a quite similar thing from a Coxian perspective.8 And again today, when a popular, if not mainstream, position is that race (or indeed race as caste) is the primary social determinant for all of life’s prospects, and solidarity among working people is considered hopelessly quixotic, if not politically and ethically suspect, it is wise to reconsider Cox’s materialist critique of these abstract formulations.