The prominence of the portrait’s creator, Wilhelm Schadow, was undoubtedly a factor in the newspaper’s interest, as was the meteoric rise of his pupils, who in 1828 had become known as the Düsseldorf School of Painting. The Hannoverian critic was indeed particularly pleased to see several important examples of that school and its founding father exhibited in his hometown, and commented enthusiastically: “Schadow’s picture meets us so completed, so self-contained and rounded out, and differs precisely thereby from portraits of the ordinary kind, that one soon recognizes the history painter in the hand which created it.”2 Smitten by its loving execution and technical perfection, the critic continued that “one doesn’t believe to see in front of us a portrait from our own shallow times, living merely for the moment, but from the times of the great Italian masters”!3

Yet, for all its allure, the portrait shrouded itself in mystery. Its descriptive title, A Bearded Man, did little to quench viewers’ curiosity about the sitter, a curiosity the reviewer conveyed through a conversation between two ladies he allegedly had overheard during his own visit:

The First: Who, then, may this interesting man be?

The Second: It is supposedly a painter in Düsseldorf.

The First: Impossible!—how could a painter look like this;—it must at least be a count.4

The ladies’ dialogue is revealing. It shows a deeply rooted desire for social legibility, while highlighting the period’s obsession with questions of genre—with the particular form, content, technique, and norms defining categories of painting. These issues were very much on Schadow’s mind as well.

Wilhelm Schadow: Anti-Academic Rebellion and Academic Reform

Born in Berlin as the second son of the famous sculptor Johann Gottfried Schadow, Wilhelm had first made his name as a member of the secessionist Brotherhood of St. Luke, which, in 1809, had set out to reform contemporary art by reenchanting it.5 With youthful idealism, the fraternity had declared that Art should once again become religion’s maiden, in subject matter as well as style, because it was Art that could spearhead an all-encompassing return of modern society to the Christian faith. Together with this belief, Schadow had also absorbed a devotional, contemplative approach to grand history painting. The Brotherhood’s artistic principles still informed Schadow’s practice as painter and professor when he became a powerful prince of painters more than two decades later. Only two years after his arrival at the Rhine, Schadow sent his first group of students to the biannual exhibition of the Berlin Academy, which the young Turks took by storm. Dedicated to the modern medium of easel painting (rather than the Nazarene obsession with fresco, celebrated in Munich), Schadow succeeded in transforming the somewhat moribund institution into an utterly modern training ground. By 1830, the Düsseldorf Academy was the place to go.

For a decade and a half, Düsseldorf could compete with such traditional art centers as Paris, and even come out ahead. As a result, a remarkably international student body flocked to the Rhenish city, and it is noteworthy that one of the icons of American history painting, the 1851 canvas Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Leutze, was born there, at the banks of the Rhine, and thus has dual citizenship.6 What made the institution so attractive was not least the particular leadership style of its director. Schadow’s “naturalist idealism” and flexible definition of the traditional hierarchy of genres opened up a space of experimentation simultaneously conservative and avant-garde, traditional and experimental.7 This was particularly true for the venerable category of academic history painting and its newly arisen competitor, the so-called genre historique, which, by privatizing its heroes and abandoning the focus on cathartic turning points, proposed a fundamental rearticulation of what constituted history in painting.8 Promoting a kind of “soul painting,” which replaced action-laden plots with a focus on mood and a psychological exploration of the protagonists’ state of mind, Schadow expanded history painting to all forms of historical imagination and in the process located its origins in portraiture.

Despite Schadow’s far-reaching reform of traditional history painting, he rarely produced work that would push the boundaries of academic norms to the extremes reached by his students (fig. 2; see also fig. 20). Indeed, Schadow’s own practice and emphasis on religious painting have long overshadowed his advocacy for the kind of testing of pictorial patterns advanced by his most famous proteges, like Eduard Bendemann or Carl Friedrich Lessing.9 For most of the time, Schadow the painter was too bound up in the Nazarene project of his youth to realize the radicalness of Schadow the professor. Similarly, he rarely tackled the thorny question of how to paint contemporary history, of how to make manifest the events of the here and now (or, for that matter, the new subjects of an urban reality not much later put center stage by the “painter of modern life”).10 However, in the early 1830s, something changed.

Around the time of his second visit to Italy from September 1830 to July 1831, Schadow produced a series of large-scale portraits which transformed his lessons into pictorial practice. The Bearded Man we encountered at the beginning of this essay was a particularly noted example of this experimental moment. Yet for all the attention it attracted it was de facto tied into other works, most importantly into the slightly earlier, monumental tondo of two Prussian Princes, The Princes Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig von Preussen and Wilhelm zu Solms-Braunfels in Cuirassier Uniform of 1830 (fig. 8).11 Equally striking and equally unknown until today, the two canvases form striking counterparts, and indeed, the strategies applied in The Bearded Man could not be fully understood without the royal commission as its essential foil.12 Taken together, the two works emerge as a testing ground for Schadow’s ambition to push the limits of the genre. While The Princes became Schadow’s prime example in his redefinition of the parameters of royal portraiture (a painting type he detested despite its importance for his own career),13 he proposed a radical alternative in The Bearded Man, which seized the same pictorial vocabulary in order to set the scene for an entirely common, utterly unknown man, who hardly warranted (in the eyes of the time) such a grand historicized portrait and indeed had neither commissioned it nor would ever own it. In applying the strategies of modernized royal portraiture to The Bearded Man, Schadow defended portraiture as a genre on par with history painting. Put differently, The Bearded Man stood as the essential expression of Schadow’s larger project, an expression that elevated portraiture to a mode of painting capable of articulating central ethical, historical, and poetic concerns, a mode of free invention and poetic imagination fully independent of stale conventions or commercial interests.

The Stakes of Historicizing Portraiture

In the 1830s, the political and aesthetic stakes for this kind of historicizing portraiture were high. With their technical bravura and enigmatic psychology, Schadow’s two portraits clearly positioned the Prussian painter vis-à-vis Paris: not only vis-à-vis Paris as one of Europe’s dominant cultural capitals and birthplace of the modern academy; but also vis-à-vis France as a symbol of revolutionary unrest and anti-monarchical violence, both of which the academy director despised with a vengeance. As such, the two canvasses answer to the burning quest for an identity for a German nation not yet unified. In this sense, they try to be as much German as Prussian, which in itself was not an easy balance to achieve. Yet Paris was not the only battleground. The portraits also summed up Schadow’s particular place within the German art scene, where his naturalist idealism stood between the radically idealist strand of late German Romanticism, then embodied most prominently by Peter Cornelius’s Munich school, and the increasingly thunderous calls for greater realism and an overthrow of academic values, in particular the lingering privilege of traditional academic history painting. Caught in the crossfire, Schadow answered with a delicate fusion of Romantic historicism and an emphatically contemporary mode of observation.

This attempt at fusion was not just a stylistic challenge for Schadow, the artist. It rather spoke to an underlying dilemma in the early nineteenth century. In an age acutely aware that revolutionary upheaval had broken the continuous thread of history, the question of how a modern identity would navigate between the desire for historical continuity and the need for contemporaneity was as crucial as it was painful. After all, even Charles Baudelaire desired to distil the eternal from the transitory, and defined modernity through this gesture.14 Thus, Schadow’s pictures remind us that the geo-political desire for a German identity intersected with the specific desire undergirding the more general quest for a modern identity.

These various concerns were wrapped up, as the fictive conversation of the ladies from Hannover so vividly demonstrates, in an intense battle over the organization and ranking of pictorial modes of painting, a battle nurtured by broad social conflicts and the effects of a rapidly changing social make-up with its rise of new audiences and new demands of the marketplace. Choosing a genre ranking quite low in the traditional hierarchy, Schadow felt free to explore a number of pictorial solutions responding to this complex mixture of artistic and political concerns, solutions that were thus necessarily high-stakes in ideological and aesthetic terms.

Preoccupied with a Romantic notion of subjectivity and haunted by a sense of modernity as a realm of alienation, Schadow decided to place his own art, and with it the subjects of his portraits, in the middle of the brewing conflicts marking the roughly two decades leading up to the Revolution of 1848. Ultimately, he used this gesture to carve out a space of his own, as painter and engaged citizen. The results were works that, from a pro-monarchist perspective, modernized academic painting from the top down. As such, The Princes and The Bearded Man proposed an evolutionary model, a model of reform rather than revolution. Inevitably, this model asks us to change our views of how modern, ambitious, and advanced portraiture could look in 1830. In so doing, it adds a crucial supplement to the revisionist histories of ambitious nineteenth-century painting and the other modernity of academic art that has brought back into the limelight figures like Paul Delaroche and Jean-Léon Gérôme.15 Tracing the genesis of these two exceptional and pictorially breathtaking works, this essay explores the pictorial economy of portraiture as history at the intersection of politics, aesthetics, and exhibition practices.

Pecking Orders

Looming large behind the era’s obsession with genre was an acute crisis into which Europe’s academies had tumbled in the early decades of the nineteenth century. It was fueled by an equally obsessive preoccupation with theorizing the status of history painting, especially, but not only, in Germany. One may be reminded here, too, of the transnational nature of these debates, exemplified by the reception of Paul Delaroche.16 The remarkably intense discussions unleashed by his evocations of dramatic events from the history of western Europe exerted a remarkable influence across the Rhine. In particular Delaroche’s life-size canvases represent an important foil to the production in Düsseldorf. Theodor Hildebrandt even travelled to Paris to inspect Delaroche’s Princes in the Tower for his own treatment of the heart-wrenching murder scene from William Shakespeare’s Richard III.17 Hildebrandt’s final solution would follow a much earlier composition, invented by the British artist James Northcote and circulated widely in various reproductive prints.18 It nonetheless shared with the Frenchman’s psychological cliffhanger, which depicts the two startled young boys just minutes before their assassination, the intense appeal to the viewer’s empathetic participation.19 In both cases, this demand for an emotional and engaged reliving of the historical moment, itself transmitted as poetic imagination, aimed at the audience’s political activation.

The emphatically political quality of the mid-1830s genre historique was missing from its late eighteenth-century roots, a kind of painting that, generally subsumed under the term “troubadour-painting,” had begun to visualize the life of “great men” as private spectacle.20 This early expression of a Romantic sensibility excelled in meticulous, miniaturized treatments of historical scenes, usually from the Middle Ages or the Renaissance, which tended toward the sentimental and combined a preference for small-scale formats with an exacting execution and lavish attention to costume, setting, and detail realism. As such, this historicist practice was materialist without being realist.21 The traces of the troubadour tradition are all too visible in Delaroche’s jewel-like composition The Assassination of the Duc de Guise of 1834. However, this reincarnation of an earlier practice distinguishes itself from its predecessors’ loquaciousness through an intricate temporality and a spatial disposition that structures the visual field as panoramic and, implying two separate areas of focus, organizes it around a blank sought to invite the spectator’s projection.22 In a nutshell, the modern genre historique combined the characteristics of two picture types previously strictly separated in the hierarchy of genres: history and genre painting. Once it reached a certain monumentality, this combination began to undermine central rules of history painting.23

Schadow was no foreigner to such anti-academic rebellion. After all, at the age of twenty-five he had joined the secessionist Brotherhood of St. Luke, which in 1810 had left the forbidding climate of the famous Viennese academy for the creative, if poverty-stricken, freedom of expatriate life in Rome. Hailing art as religion’s most powerful maiden, the fraternity pursued a two-pronged approach. It proclaimed a need to revive grand religious history painting, and indeed achieved its international breakthrough with a much-noted Old Testament fresco cycle.24 Yet equally important was a reform of popular print culture, which in their eyes suffered deeply from cheaply produced, artistically dissatisfying productions. Despite the daily challenges to support their own existence by pursuing their art, the Brotherhood thought about ways to create high-end quality at low costs, efforts that five decades later would celebrate a crowning and long-lasting achievement in Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld’s 1860 Bible in Pictures.25 Dubbed “the Nazarenes” by the Romans, which were rather amused by the Christ-like appearance and religious fervor of the pale foreigners, the group’s anti-academic rebellion showed through in their style and, most crucial to our discussion, their definition of history painting. Denouncing the eighteenth century as an era of decadence and decline, the young artists rid themselves of the Rococo’s playful eroticism and the ancient corporeality of Neoclassicism. Their ideal was a reborn childlike naïveté, which they found in a marriage of Raphael and Dürer, a marriage best consummated in exacting contour and local color. Schadow did not shed these rebellious impulses when he himself became one of Europe’s most powerful academy directors. Eager to make his new home at the Rhine into an international magnet, the Berlin native not only launched a substantial reform of its curriculum. He also radically modernized the conception of genre categories.

Under Schadow’s tutelage, the Düsseldorf Academy retained the traditional genre hierarchy, but by name only. In Paris, the rise of the genre historique had posed a major challenge to the academic system. In Düsseldorf, it did not. Schadow simply expanded the definition of history painting to encompass all forms of historical representation, including the genre historique. Thus, he could declare portraiture—rather than the male nude body acting out a narrative—as the foundation of all history painting. In turn, portraiture could be raised from its lower status as a minor genre by adopting the spirit of history painting, liberating it from the paying sitter’s whimsy and the demands of an increasingly capitalist art market.

Portraiture as tableau

From a young age, Schadow had himself excelled as a celebrated portraitist of the Prussian haute volée.26 Yet, just like Ingres, he saw his true calling as the author of grand histories. Consequently, he was determined to elevate portraiture from mere commodity to a genuinely poetic, even sublime genre, and thus early on experimented with religious, allegorical, and literary allusions.27 By the time he finished his studies in Rome, where he would stay from 1811 to 1819, he was able, as Henriette Herz enthused, to upraise any likeness to the status of a tableau.28 The prominent Berlin salonnière might have had in mind Schadow’s precocious rendition of the Princess Marie Anne von Preussen (fig. 3). Begun in 1810 while still in Berlin but finished only two years later in Rome, the sumptuous likeness belonged to the most political works of Schadow’s early career.

In the year of the portrait’s conception, Prussia was mobilizing to throw off Napoleon’s yoke. Seized by the moment’s patriotic spirit, the ambitious young artist shared the fierce and fearlessly anti-Napoleonic attitude of his key patron: he thus set out to express this mutual sentiment when granted the rare occasion to paint the Prussian princess, who famously disliked modelling for royal portraiture as much as she did court ritual.29 Schadow quickly realized that he had to achieve his goal through sartorial means. Of all things, it is thus the old German dress that signals the likeness’s emphatically political agenda.

At first glance, the sumptuous testament to the period’s Renaissance revival might easily be dismissed as the typical fashionable excess of a high society harboring a seemingly insatiable desire for costume balls and other occasions for dress-up.30 However, in this case, the sartorial choice pronounced a daring avowal of resistance against the French occupation. Like her close friend, the recently deceased Queen Luise, Princess Marianne belonged to the so-called war party, die Kriegspartei, those Prussian circles that deemed a military advance against the steadily growing power of Napoleon unavoidable.31 This moment finally came when Prussia joined the allied forces against Napoleon in the War of the Sixth Coalition, better known as the War of Liberation, almost exactly a year after Schadow had finished his splendid likeness shortly after New Year’s Day in 1812. Not surprisingly, the intrepid princess immediately assumed a leadership role in the war effort. Inspired by the increasing female initiatives in the field of “patriotic charity,” Marianne masterminded a declaration of twelve Prussian princesses, including herself, which provided the commitment of these “female patriots” with official support and royal backing. “The fatherland is in peril!” declared the Appeal to the Women of the Prussian State with arousing pathos on 23 March 1813. “Not merely cash money will our association accept as a sacrifice but any spare valuable bagatelle,—the symbol of fidelity, the wedding band, shining adornments for the ears, costly decorations for the neck. Monthly contributions, material, linen cloth, spun wool, and yarn will be gladly accepted, and even the gratis working of these raw materials will be regarded as an offering. Such donations, gifts and activities entitle one from now on to call oneself ‘Member of the Women’s League for the Welfare of the Fatherland.’”32 Schadow’s portrayal of Marianne in old German dress anticipates the combative stance of a noblewoman who otherwise preferred informal privacy to the formality of court spectacle. It realized in pictorial terms Ernst Moritz Arndt’s request that the Germans should not merely remember their glorious history and national freedom, but also make public their convictions through their attire. Accordingly, the princess wears directly beneath her collar the gold ducat of Friedrich II, which identifies her as a descendant of the war hero of Fehrbellin, where the united Brandenburg-Prussian troops had defeated those of the occupying Swedish Empire in 1675. Not coincidentally, the various reproductive prints carefully capture this crucial detail. The young Schadow, too, sympathized with Arndt’s sartorial ideology and expressed his patriotism by flaunting, while still in Rome as a brother of St. Luke, the so-called German frock (fig. 4).

This emphatic musing on the public and the private side of his subjects was rare in Schadow’s oeuvre: he would not engage in such overtly politicized portraiture for at least twenty years. Then, two decades later, it would not be attire but nature herself that became charged with the picture’s symbolic work (see fig. 8).

Poeticizing Portraiture

Perhaps the most famous example of the transformation of likeness into symbolic representation, as evoked by Henriette Herz, is Schadow’s self-portrait in an atelier scene with his brother Ridolfo (like their father, a sculptor) and their mutual mentor, the Dane Bertel Thorvaldsen (fig. 5), painted toward the end of the artist’s Italian sojourn. Much could be said about this seminal work, painted around 1815 or 1816, at once friendship portrait and character study, allegory and programmatic testimony to the Nazarene creed that a rebirth of modern art must grow, in its need for reenchantment, from a synthesis of North and South or, put differently, from the marriage of Italia and Germania.33 The picture ultimately delivered an astoundingly fresh rephrasing of the classical paragone debate. For many reasons, not least the setting and the captivating realism of the physiognomies, the picture would remain an anomaly in Schadow’s oeuvre and in the Romantic production of his brethren. For the same reasons, it has earned—among only a handful of Nazarene works—a place of respect and admiration within the accepted canon of nineteenth-century European art.

Other works, however, also deserve to be recuperated from their current obscurity, not least the child portraits of Schadow’s Roman period and early years back in Berlin. These pictures—like the 1819 portrayal of Wienczyslaw and Konstanty Potocki or the rendition of Rose, Kurd and Karl von Schöning executed three years later, in 1822 (fig. 6 and fig. 7)—rehearse on a stylistic level Schadow’s intense engagement with the Northern Renaissance that would return in the Bearded Man’s iconography, dress code, and composition. Less known than his famous studio scene of 1816 (fig. 5), they are important in understanding Schadow’s further development, above all his deliberate poeticization of portraiture through an amalgamation of an old German idiom with that of the Italian quattro- and cinquecento.

The 1819 likeness of the Polish princes, for example, bears witness to the cultic quality of Raphael’s most famous work on German soil, the Sistine Madonna. Schadow had seen this icon of the German cult of Raphael in 1810, on his way to Italy (fig. 6).34 His adaptation of the Dresden image represents perhaps one of the most unexpected of the works made after this painting. After all, the angelic witnesses of the Virgin’s apparition have mostly inspired rather schmaltzy variations of Raphael’s ingenious invention. Schadow’s putti, however, have shed their ancestors’ lighthearted mischievousness. Despite an almost verbatim citation of their postures, their mood has become rather contemplative, if not outright somber. Indeed, the wistful interiority of Schadow’s sitters seems somewhat at odds with their tender age, as the princes were merely two and four years old when they modelled for the Nazarene painter. This change in atmosphere continues throughout the reinterpretation of the picture’s Italianate elements via the notable severity of contour and paint application. Schadow would repeat this operation—this tension-filled fusion of cis- and transalpine Renaissance modes—when he captured the Schöning children three years later.

Marked by an equally harsh contour, the life-size figures of Rose, Kurd, and Karl share with their Polish cousins the same peculiar sensation of a gravitas and sincerity far beyond their youth (fig. 7).35 At the same time, the dialectic of Northern and Italian models is even more pronounced, not least because Italia asserts herself with a brilliant luminosity and bold tonality quite unusual in Schadow’s oeuvre. Indeed, the vitreous, lucent colors, especially the sky’s blazing lapis lazuli, would have made even Giovanni Bellini proud. They create such a dramatic and drastic effect that it inevitably strikes the modern viewer as audacious.36 It almost seems as if the canvas’s Venetian incandescence served the recent repatriate as a means of working through—and ultimately overcoming—his raw longing for the South he had just left behind. This highly personal way of working through his own longing and nostalgia shines through in the painter’s efforts to elevate the portrait to a more sublime format. The notion of childhood play yields to an exacting triangular composition that arrests movement in ethereal harmony and the breathing body in sculpturesque immobility. In the process the image acquires the air of a devotional painting, an effect heightened by a selection of plants and attributes distinctly Marian in character (or associated with the Passion of Christ). Thus, the triad of red, blue, and white dresses, for example, recalls the Virgin’s colors, while the dove, cherries, and lush vine in the background are common appearances in depictions of the Christ child.37 In 1822, Schadow transformed child portraiture into a modern altarpiece.

In response to his second, much-desired visit to his beloved Italy from September 1830 to June 1831, Schadow would perfect his means of poeticizing portraiture. I have discussed these efforts elsewhere.38 Here, I want to focus on his perhaps most intriguing attempt, undertaken shortly afterwards, to make over likeness into historie, most intriguing because it for once left behind the tried-and-true pictorial conventions Schadow had previously transferred onto portraiture from religious and allegorical painting. The result was the admired Bearded Man of 1832, to which we shall return now.

Portraiture as Politics

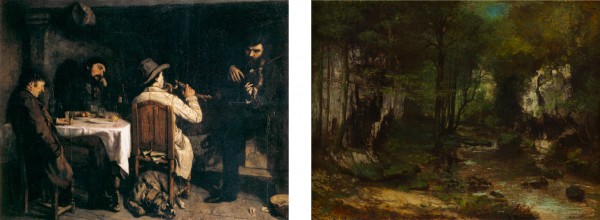

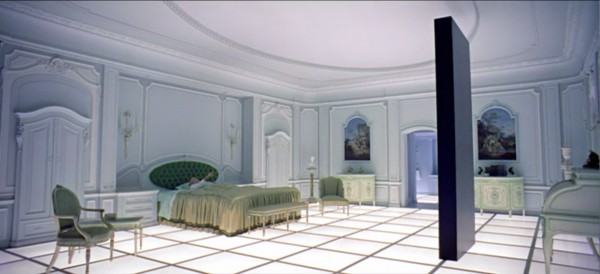

The secret to our mystery man’s success was an ingenious fusion of two seemingly contradictory strategies. On the one hand, Schadow emulated—in format, composition, outfitting, and décor—the old German tradition (see fig. 15 and fig. 19). On the other hand, he alluded to the politically charged iconography of the contemporary royal likeness. Only two years before his Bearded Man took Hannover by storm, Schadow created one of the most daring experiments in his rich portrait production, which, with a diameter of fifty-one inches, is also one of the largest: The Princes (fig. 8).39 The visual impact of the magnificent tondo derives not least from the subtle yet powerful juxtaposition of the sitters’ political role and their intimate personal relationship, or, to put it differently, from the finely orchestrated contrast between the public and private sphere.

Standing almost uncomfortably close to the picture-plane, cut off by the frame at three-quarter length, the two nephews of Friedrich Wilhelm III, the ruling Prussian king, greet us as commanding figures, their hands firmly grasping their swords, the polished metal of their harnesses flickering seductively. Their poses convey royal stature as much as military prowess, as manliness mingles with courtly elegance, and the display of strength with a sense of graceful comportment. Yet for all the princes’ glory, they stood out. In an era teeming with noble likenesses, this one was not satisfied with a stately aura or the tired trope of noblemen depicted against a backdrop of storm-tossed landscapes and wild skies. Instead, such overly simplistic tropes yield to sensitive psychological observation and a deeply felt interest in the half-brothers’ individual characters. What is at stake here is a subtle exploration of a relationship overdetermined—as the picture makes clear at first sight—by a complicated mixture of familial love and raison d’état. Schadow’s genuine concern for the princes’ different dispositions bestowed upon the ensuing canvas a depth and unexpected intimacy that personalizes its outspoken political iconography. This infusion of a Romantic subjectivity and sensibility into the format of a monarchical state portrait engendered a broader reform of that genre’s conventions. In this sense, the interplay of royal commission and highly personal character study, which in this context was rather unconventional, produced an interplay of the private and public spheres worth further investigation.

Border Crossings

The double portrait of the Prussian princes Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig von Preussen and Wilhelm zu Solms-Braunfels occupies an exceptional place within Schadow’s oeuvre. Its singularity begins with the format, the tondo, which the painter liked for its intimate qualities but explored here on a monumental scale. Producing a daring oscillation between closeness (both physical and emotional) and imposing domination, the format itself thus serves as a signpost for the portrait’s essential function: the representation of private and public personas at once. The scale also gives weight to the background, a feature that Schadow usually treated mostly as a second thought, a mere foil. Here, in contrast, the landscape gains visual and symbolic prominence. The rare selection of a German veduta and its equally rare evocative realism go hand in hand with another dramatic departure from Schadow’s practice, the willingness to overcome his deep-rooted aversion to ornate, contemporary dress, which here manifests itself in the sitters’ opulent military uniforms. These formal strategies grew out of Schadow’s decision to tackle once more, the first time since his early rendition of Princess Marie Anne von Preussen in Old German Dress (fig. 3),the task of exploiting portraiture’s political potentialities.

Schadow’s return to portraiture as politics reflected not merely the sitter’s social station and political importance for Düsseldorf and the Rhineland, where Prince Friedrich, as the nephew of King Friedrich Wilhelm III, occupied a seminal role as a kind of “Ersatz king.”40 Beyond the painter’s general monarchist leanings, it paid a personal tribute to Schadow’s cordial relationship with the musically gifted aristocrat who, having arrived at the Rhine only five years before the new academy director, harbored a genuine interest in the arts. In his memoirs, written in 1861, Schadow noted fondly that “when I think of support [for my work], I have to mention above all Prince Friedrich … The personality of this most worthy gentleman was fitting to win the hearts of the Rhinelanders. He united dignity and the most refined propriety with an affability that made everybody in his presence comfortable and cozy … His conversational style was gripping for its natural charm, which, combined with the allure of manly beauty, entranced not only all women but conquered the hearts of the men as well. [Naturally,] this lively intellectual welcomed a new element to breach the elegant yet monotonous society of petite Düsseldorf. He gathered the artists around him, who in return gratefully offered their talents in service of his festivities, visited the studios and participated in every success of the young academy. Thus, he demonstrated more trust in the painters than did Düsseldorf’s bourgeoisie, who at first had not wanted to bring them into their houses.”41

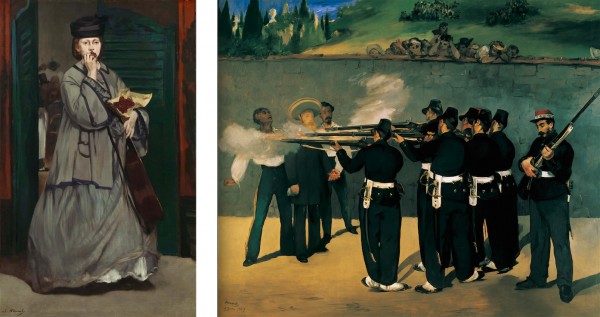

Nothing testifies to Prince Friedrich’s genuine commitment to the city’s artists and their cultural endeavors more than the Hohenzollern’s willingness to break with court etiquette and attend an evening of tableaux vivants and theatrical performances in Schadow’s private residence.42 He was accompanied by his equally cultured wife, Wilhelmine Luise, born Princess von Anhalt-Bernburg and herself an amateur painter (fig. 9) who was popular among artists and art students for her modesty and genuine understanding of the arts. Schadow felt great sympathy for the Princess Friedrich, as she was also known, and painted her around the same time as her husband. The ensuing likeness was a far cry from the stereotypical “princess portraits” populating palaces and popular press alike. The subtle color combination of dusty blues, saturated forest green, the rich dark hues of the fur’s deep brown, and the jet-black hair of the sitter sets a tone of understated elegance, which reflects back on the princess’s persona. Her carefully rendered features seem, despite their obvious perfection and the flawless skin, realistic rather than overly idealized. They invite us to break through the surface of carefully styled beauty and the luxurious cocoon of the latest fashion to a level of sensibility and emotional immediacy at odds with the self-control and public façade demanded by her royal status. In this sense, the likeness of Princess Friedrich lives off the same strategies, albeit on a much smaller scale, than that of her husband.43 Schadow’s interplay of intimacy and public persona spills over into the portrait’s aesthetic temporality, which counters the emphatic contemporaneity of sartorial choices and the intricate coiffure, with a rather poignant citation of Italian High Renaissance portraiture. With a nonchalant gesture, firm and yet unstrained, her left hand grasping her coat’s overabundant fur trimming, Wilhelmine Luise joins an impressive gallery of females from the past, from courtesans to goddesses, who were captured in exactly that pose; in the process, her likeness is elevated from the merely fleeting depiction of the contemporary to an essential timeless ideal.44

Beyond the obvious art historical citation, the Renaissance inflection of Wilhelmine’s appearance also ties her portrait back to the social reality of Düsseldorf’s active theater scene, which could thrive as it did through the remarkably sizeable participation of amateur actors recruited from art academy and military alike. Given the royal couple’s sincere and affectionate dedication to the local art scene, it is less astounding to learn that the two indeed accepted leading parts in one of the plays staged by the academy director. Little is known about either its content or the actual performance, documented merely by a now-lost pencil drawing which names the various participants who appear in costume, and a charming portrayal of the painter’s sister-in-law in Renaissance costume (fig. 10).45 In this context, the small but exquisite painting functioned simultaneously as true likeness and marriage portrait, historical genre scene and the depiction of a (fictive) tableau vivant. It paints realism as idealism. As such, the likeness of Johanna “Jenny” Groschke, who met her aristocratic husband during the event, testifies to the overarching importance of the theme of border crossing to Schadow’s practice at this time, a theme pertaining as much to art as life and, in true Nazarene manner, to life through art.46

The popularity of Prince and Princess Friedrich did not even diminish when the political climate grew increasingly tense during the years leading up to the Revolution of 1848. Only the fierce anti-monarchical demonstrations, which would rattle the city in March of that fateful year, finally engendered a bitter break between the Prussian general and his adopted Heimat. Under protest, Friedrich von Preussen left Düsseldorf, never to return. Not even the sincerest efforts of the city, which offered him honorary citizenship in 1856, could change his mind: he thus never set foot again in his beloved residence, the Jägerhof.

1829, Brotherly Love and Prussian Prowess

Of course, when Schadow received the commission for the double portrait, such revolutionary unrest was still a long way off, as were the turbulent frictions within the art scene that would later weigh so heavily on the academy director. In 1829, the Düsseldorf School of Painting celebrated spectacular successes, and life together, inside and outside the studio, was almost alarmingly harmonious. At this high point of Schadow’s social experiment, running an academy like an artist fraternity, Friedrich von Preussen approached him with the idea of a likeness together with his younger half-brother, Friedrich Wilhelm zu Solms-Braunfels. Despite a family history that was not without tensions, the two men were extremely close, and the painting was probably intended as a gift for their mother, Friederike Sophie von Mecklenburg-Strelitz. At this point, the sister of Queen Luise was betrothed in her third marriage to the Duke of Cumberland. It is also possible that the son had merely communicated a commission from his mother, who had only recently, in 1828, visited Düsseldorf and on that occasion quite likely met the academy director. In any case, once the plan was born, work commenced speedily.

Already in 1829, the princes sat several times for Schadow. Complications arose as Wilhelm was stationed in Berlin-Potsdam and thus could not attend as many sessions as needed. Without further ado, the brother simply asked one of his officers to fill in. On 8 December 1829 a brief note was dispatched with the request to arrive in full uniform, “with cuirass and helm,” so that the painter could project pose and painterly effects.47 The note’s informal, satirical salutation—“Worthiest Rhine-Salmon”—most likely presents a witty word play on the name of the castle Burg Rheinstein, which the prince had recently purchased and was in the process of renovating.48 It certainly highlights the prince’s humorous side, which was well known and much loved in a city enamored by the yearly carnival and its soapbox speeches. The identity of that Rheinlachs, however, has remained a mystery demanding a fair amount of speculation to solve. The rather comic nickname certainly suggests an affectionate relationship to a person from within Friedrich’s closest military circle, and here the prince’s artistically inclined adjutant Carl Friedrich Rudolf Ernst von Normann comes to mind.49 Later in life, Normann would exchange sword for paintbrush for good; but even while still pursuing a thriving military career in the Düsseldorf regiment, this distinguished and elegant officer had joined the local academy as a dilettante member. Thus, it seems more than likely that it was him who showed up “at 11 am … in Director Schadow’s room” to pose for the picture.50

Once the canvas was finished, a lustrous frame, partially gilded, partially covered with gold foil, added a luxurious final touch. Thus embellished, the impressive double portrait made its social debut at the 1830 spring exhibition of the Düsseldorf Academy before it travelled in September to Berlin, where the academy’s biannual exhibition opened its doors on the 19th of that month. The favorable review in the influential art journal Kunst-Blatt noted that the monumental tondo was marked to cross the channel, where its new owner, the Duchess of Cumberland, would welcome it shortly afterwards.51

If the princely portrait stood out among Schadow’s many fine portraits for its size and its attention to clothing and landscape, it also distinguished itself in its haptic sensuousness and the plasticity of its surface values. It almost seems as if the opulence of the cuirassier uniform had thrown down a gauntlet that, once accepted, led Schadow to show off his technical prowess. The result is a rich play of enticing contrasts, from the juxtaposition of the fur’s plush softness and the coldness of the harness’s impenetrable metal, or of shimmering polish and the coarseness of the jacket’s gleaming-white kersey. The reflections on the brilliant cuirass especially show off Schadow’s paragone with the old masters. Despite these carefully executed visual pleasures Schadow nonetheless took great pains to avoid a dispersal of attention. The restrained tonality and the enamel-like paint application are means to secure an effect of overarching harmony and quiet grandeur. Handling color in the most local terms, the painter built the entire portrait around the classic triad of red, blue and a golden yellow, which, brought to sparkle by a few lively color accents, creates a calming effect of restfulness mingled with a cool, sophisticated elegance.

Schadow’s pictorial strategies translated directly into his approach to the study of the two men’s characters; they thus correlate with a stunning back-and-forth between a sense of collected reserve and emotional intensity. Drawing the viewer in, not least through the figures’ bold cropping and firm inscription into the picture plane, the portrait nevertheless commands a respectful inner distance between the viewer and the imposing princes. Struggling with these conflicting impulses, we experience an almost physical realization of the portrait’s overarching theme: the interplay of private and public spheres, an interplay both productive and contentious and embodied in a duality of brotherly friendship and political alliance.

In The Princes, Schadow for once embraced the call for an emphatically representative state portrait, and moreover one unabashedly military in character. This explains the fastidious care with which he painted the uniforms, which provide an almost seductive entrée for one of Prussia’s most elite and feared troops. Despite the sartorial splendor, the overall atmosphere is not one of showiness but of quiet grandeur. Citing Renaissance monarchical portraiture and devotional painting, the tondo format adds a sense of sublimity and even the sacred. The pictorial rhetoric of power and prowess, however, does not obliterate Schadow’s Romantic sensitivity. On the contrary, the valor goes hand in hand with heartfelt emotion, and the double portrait fuses, with surprising boldness, the longstanding tradition of representing nobility with the newly minted genre of the Romantic friendship portrait, a fusion even more remarkable for its execution on a monumental scale.52

The Monarchical State Portrait as Friendship Portrait

When first exhibited, the Kunst-Blatt commented with awe on the sitters’ “solemn princely pose.”53 But perhaps more remarkable is the expression of brotherly affection manifest in the embrace by the older man, Friedrich, of the younger, Wilhelm. This motif gains a truly Romantic note in the paradoxical mixture of physical closeness and divergent gazes, which continues the tradition of picturing friendship as an inner state of union, of kindred spirits, rather than conversant interaction.54 Accordingly, only Wilhelm’s frank look acknowledges the viewer; Friedrich, in contrast, seems lost in thought, and the slight melancholy, which hovers at the edges of his enigmatic expression, suggests musings of a rather private nature, perhaps even regarding matters of the heart. Thus, his portrait not only flaunts an officer and gentleman; it also proclaims a quintessentially Romantic ideal of manliness, one not driven by strength but sense and sensibility. His self-absorption and reflective inwardness create a poignant antipode to Prince Wilhelm’s aura of determination, assertiveness, and physical agility paired with considerable strength, as latently suggested by the taut, muscle-flexing posture. This subtle yet striking character differentiation avows its roots in the Romantic friendship portrait, insofar as it implies a complimentary, indeed symbiotic relationship. A finely tuned rhythm of mutual giving and taking dominates the composition, as the older brother at once promises protection while relying on his sibling’s support. The social hierarchies separating Friedrich, the lieutenant general, and Wilhelm, the cavalry captain—hierarchies reflecting not merely the men’s different military rank but also respective place in the line of succession—thus yield to an affirmation of equality, an equality built upon love, tenderness, and familial loyalty.

Schadow’s strategy of fusing the Prussian portrait tradition of high nobility in uniform with the novel type of the Romantic friendship portrait finds its ultimate embodiment in the picture’s most eye-catching detail, the expertly painted reflection of Wilhelm’s hand on Prince Friedrich’s polished cuirass exactly beneath his brother’s heart. The mirror-image of Wilhelm’s right hand, the hand of oath-taking, immediately takes on symbolic meaning, judiciously framed, as it were, by two prestigious medals: the large Order of the Black Eagle on orange ground, affixed to Friedrich’s right hip, and the simple black Iron Cross of the Second Class. Attached above the prince’s heart—and thus above the reflection of his brother’s hand—the Iron Cross proudly commemorates Friedrich’s bravery during the sensational Rhine crossing of Prussian troops at the old German town of Kaub, located about forty miles northwest of Wiesbaden, in the New Year’s week of 1814. Orchestrated by Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, affectionately nicknamed “Marshal Forward” by his soldiers for his aggressive approach in warfare, the astonishing movement of 50,000 soldiers in three days carried the War of Liberation back into France and marked the beginning of Napoleon’s end.55 The reflection of Wilhelm’s hand thus must be read as the insignia of a military oath and loving testimony at once, of one brother touching his sibling’s heart both physically and metaphorically, a gesture almost too intimate for a large-scale state portrait and yet so appropriately political. With love, a life is pledged to Prussia’s dominion and military pursuits.

The New Knights at the Rhine

For all its surprising freshness, Schadow’s iconography could look back to a long tradition of pictures commemorating political alliances, and here Pompeo Batoni’s 1769 double portrait of the Austrian Emperor Joseph II and his brother, Pietro Leopold I of Tuscany might come to mind.56 Likewise, the nuanced characterization of the prince’s complex relationship had an immediate model, and one most closely related to the princes and their painter alike: the 1797 double statue The Princesses Luise and Friederike (fig. 11). Designed by Schadow’s father, Johann Gottfried, in plaster in 1795 and then executed in marble in the subsequent two years, this icon of Berlin sculpture shows the queen with her younger sister, the mother of Friedrich and Wilhelm. Its notable play of closeness and distance, paired with a graceful eroticism, took its inspiration from an antique source, the late Augustan marble of San Ildefonso. Dating from around 10 AD and rediscovered in 1622, this superb model of ancient eclecticism had made a spectacular entry into the German imaginary in 1707, when the electoral prince of the Palatinate, Johann Wilhelm, commissioned a plaster cast and thus brought the youthful pair to Mannheim. Identified respectively as Orestes and Pylades or Castor and Pollux, the group impressed the era’s literati, above all the Olympian of German poetry, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. After having spent “the most blissful moments” in the boys’ presence, Goethe went on to commemorate the two not only in his autobiographical writings Poetry and Truth but also in his influential plays Götz von Berlichingen and Faust. The poet even ordered a copy of the Mannheim cast for his own house.57 Tapping into this rich, rather intricate genealogical lineage, the tondo of the Hohenzollern princes thus embodied a twofold familial homage, once in the form of a tribute by the painter to his father, once by the royal officers to their mother, Friederike.

Given the unusual character of the princely portrait, it seems hardly surprising that Schadow also rethought his treatment of the background. Embracing the uncompromising contemporary nature of Friedrich and Wilhelm’s appearance and worldly station, he expanded the picture’s political meaning into the landscape, a beautifully rendered view of the Rhine river. In most of his work, landscape merely functions as a means to set a certain mood or reiterate the painting’s historicist nature as a stylistic citation of models from a medieval past, preferably Raphael.58 Now, he embarked on a highly realistic veduta. The juxtaposition of the royal sitters and the Rhenish scenery asserts Prussia’s claim to rule over the Rhineland, a territory it had only recently acquired during the Congress of Vienna (1815–1816). Yet once again, the proclamation of power comingles with an emphasis on emotional investment. The princes’ poses are not merely one of repressive threat. Rather, the sensitive evocation of their inner landscape translates into a deeply felt love of the new Heimat, the now Prussian Rhineland, and a longing for embeddedness. The assertion of rule is also a pledge of loyalty, a pledge to take good care of the new land, of its rich history and heritage. In the case of Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig von Preussen, this commitment took shape not least in his avid, groundbreaking support of historic preservation. Indeed, the prince himself had bought and then restored the castle in the background, Burg Rheinstein, which would remain until his final departure from Düsseldorf in 1848 one of his favorite places to be. Fittingly, the solemnity of the Hohenzollerns’ pose also communicates a self-understanding as the guardians of the Rhine and thus as a patriotic bulwark against the French menace. Here, we have come back full circle to the portrait of Princess Marianne and her anti-Napoleonic stance (see fig. 3). The officers’ firm grip of their broadswords, the Pallasch at their side, is sign of the victor’s pride as much as a warning of ever-lasting vigilance. As such, the monumental likeness symbolizes the Romantic quest for the roots of a German national culture, which the painting locates in the knighthood of the German Middle Ages. Standing at the edge of the Prussian kingdom, opposite the French enemy, the princes emerge as the modern reincarnation of that valiant past.

This complex set of allusions and alliances remained in play when Schadow repeated this pictorial scheme two years later, yet now with an unknown sitter as the protagonist. Hence, the forceful political symbolism made room for iconographic ambiguity and the dissolution of clear social legibility.

The Mystery of the Bearded Man

One of the secrets to the success of Schadow’s academy reform was the space it opened up for an officially sanctioned dissolution of traditional genre borders. It is only this impulse that might explain the rather puzzling choice of the model for this majestic portrait, Jacob Becker, the twenty-two-year-old son of a farmer’s daughter and a tailor near Worms (fig. 12). Later Becker would become famous as one of Düsseldorf’s most distinguished genre painters and a popular professor at the renowned Städel Art Institute in Frankfurt. In 1832, this glorious future was still a long way off. When he first met Schadow, the young man was earning a living as a draftsman and lithographer for the Frankfurt Lithographische Anstalt Vogel & Fink, where he had found employment in 1827, right after his arrival in the Main capital. The work for Vogel & Fink provided Becker with a solid technical education, which he perfected by attending elementary classes at the Städel as a guest student. A commission in 1833 to capture on stone Theodor Hildebrandt’s hit canvas Praying Choirboys would become the decisive turning point of his career (fig. 13). Warmly welcomed by Hildebrandt and the close circle of Schadow’s first generation of students, Becker decided that same year to relocate to the Rhine, where he immediately entered the landscape class of Johann Wilhelm Schirmer, only three years his senior. Seven years later, in 1840, he achieved his ultimate breakthrough with a dramatic depiction of Countrymen Surprised by a Tempest.59 Within a year he was back in Frankfurt, hired at the very institution where he had received his first artistic lessons.60

Long before he set foot in Düsseldorf, however, Becker had already met Schadow on an earlier mission. At that time he was travelling, together with his close friend and colleague Jakob Fürchtegott Dielmann, to sketch the river banks of the Rhine between Mainz and Koblenz. Commissioned by their mutual employer, Friedrich Carl Vogel, the trip resulted in a truly mammoth publication that occupies an exceptional place among the period’s popular panoramas (fig. 14). Only 9.5 cm high but 20 m long, the 1833 Leporello Panorama of the Rhine: View of the Right and Left Bank of the Rhine, Mentz to Coblentz, published by F. C. Vogel was less practical guide than precious souvenir. Becker dedicated himself to the left river bank, which he not only drew but lithographed. Without compromising the task’s necessary demand for descriptive realism, the artist aimed to capture the region’s idyllic atmosphere on the brink of its destruction through industrialization and the demands of modern travel.61 This sentiment must have greatly appealed to Schadow, who, after all, vehemently advocated an idealist approach even in realistic landscape or contemporary genre painting. Admiring Becker’s views, Schadow was equally smitten by the young man’s appearance, which he proceeded to stage, quite unbefitting of Becker’s worldly station, with aristocratic bravado.

Sartorial Strategies

Without recourse to the sartorial markers of power and prestige he had at his fingertips in The Princes, Schadow had to find an alternative way to imbue his subject with stately dignity. In the past, he had resorted to borrowing from Christian iconography, devotional painting, royal portraiture and the representation of ancient rulers, not to mention Baroque compositions, which, still vilified by the Brotherhood of St. Luke, had become increasingly popular among his Düsseldorf students, especially those of Guido Reni or Carlo Dolci. The result was what I would like to call, following the lead of Schadow’s contemporaries, the historicizing portrait.62 In Becker’s likeness, Schadow pursued an entirely different path. He solved his problem by emulating German Renaissance portraiture yet with an emphatically modern twist.

On a basic level, the set-up of A Bearded Man bespeaks a deep familiarity with Italian Renaissance portraiture, and here Leonardo’s famous Mona Lisa might come to mind as one seminal example for the placement of a sitter in an architectural loggia with a landscape background.63 And, of course, when one thinks of the grandeur of Becker’s pose, the elegance and discretion of his dress, and his intense yet simple and natural presence, Raphael’s captivating portrayal of the famous courtier Baldassare Castiglione, the poet, humanist, and ambassador, whom the artist had first met as a young man in Urbino, comes to mind.64 The two men not only share sumptuous attire and almost identical facial hair; they also mirror each other in their sideward glance and an aura of humane sensitivity paired with considerable assertiveness, a somber amiability which translates from character into composition. One might even apply to the unknown lithographer and his portrait Castiglione’s ideal of sprezzatura, an effortless self-confidence or virtuosity combined with grace, which the diplomat had celebrated as a crucial ideal befitting the man of culture in his 1528 Book of the Courtier. Raphael had translated this concept into oil in his friend’s illustrious likeness, and Schadow clearly strove for sprezzatura in his own work.65 Yet equally important, and for ideological reasons even more so, was the Northern Renaissance tradition. Indeed, composition, outfitting, and décor recall the striking likenesses of old German patricians, which by the 1830s had become a coveted body of work and of interest to collectors and scholars alike.66 Here we might want to turn to the Nazarenes’ most beloved medieval master, Albrecht Dürer, and his self-confident wearing of fur.

Dürer’s Fur

In the main commission of his Venetian sojourn, the 1506 Feast of the Rosegarlands, the Nuremberg artist proudly flaunts a richly designed mantle with a costly fur trim. Of all Dürer’s self-portraits in assistenza, this would become the most canonical. Following the impulse to isolate Dürer’s cameo appearances from his large-scale compositions, the important print-maker Lucas Kilian, for example, used this half-quarter-length likeness at least three times, once in a famous engraving of 1608 (fig. 15).67 Although this print would become one of the best known representations of Dürer to posterity, it is in fact twice removed from Dürer’s own work.68 Indeed, when Kilian set out to engrave the Nuremberg master, the original altarpiece had already been shipped across the Alps to Prague and its new owner, the Emperor Rudolf II. The print maker looked instead, as the engraving’s lengthy inscription reveals, at a replica (or maybe a partial copy) executed by Hans Rottenhammer shortly before the altarpiece left Italy. Kilian’s exacting execution, however, did not suffer from this mediation. His print is a tour de force of detail and haptic brilliance. It almost seems as if the sumptuous engraving captures a microscopic view of the Feast of the Rosegarlands, “since the original figure is proportionally speaking quite small.”69 A few decades later, the remarkable quality of Kilian’s sheet compelled Joachim von Sandrart, the “Northern Vasari,” to choose it as the model for the Dürer likeness in his own 1675 treatise Teutsche Akademie (fig. 16).70 As the first full appreciation of Dürer’s life and art to be published in his own country, Sandrart’s biography played a vital role in the rise and expansion of the master’s cultic adoration. While enshrining the Nuremberger in the pantheon of Northern artists, Sandrart’s account also secured fame and familiarity for Kilian’s likeness across Europe. Repeating the reduction of Kilian’s figure to a bust portrait in the Teutsche Akademie, a print by the Dresden engraver Moritz Steinla testifies to the image’s ongoing prominence even two hundred years later.71

Whether or not Schadow knew Kilian’s print or any of its offspring is unclear. Working on his autobiographical novel of 1854, The Modern Vasari, a book that doubles as art historical treatise and artist biographies, the academy director confessed to his collaborator, Julian Hübner, that he could not get hold of a full edition of Sandrart’s Teutsche Akademie.72 Nonetheless, both publications share a sustained interest in the physical appearance of the artists discussed, and Schadow gladly followed the suggestion of his publisher to include nine portraits of contemporary artists in The Modern Vasari. Already as a young man Schadow had been fascinated by the faces of the past. When he decided in 1819 to adorn his own father’s rendering with an image of Albrecht Dürer, he resorted to another famous Renaissance source for an accurate likeness (fig. 17). A copy of the portrait medal, crafted in 1527 by Matthes Gebel, probably belonged to the Schadow household. The inclusion of Gebel’s medal was at once a plea for appeasement and a gesture of self-assertion (fig. 18). It paid tribute to Johann Gottfried’s adoration of Dürer, while embodying a programmatic declaration of the Nazarene aesthetic. This declaration proved to be a bone of contention once Schadow was replanted in Berlin six years after joining the Brotherhood of St. Luke in 1813. Once back, he saw his artistic principles and ideological position vehemently attacked, not least by his own father. Shaped by a neoclassicist sensibility and deeply ingrained Enlightenment beliefs the sculptor could only feel contempt and disgust in the face of his son’s Romantic-Catholic conversion and the medievalist idiom it accompanied. Wilhelm thus called on Dürer for support and justification. In this sense, the carefully rendered Renaissance medal labels the portrait’s exquisite style quite self-consciously as old German. Given Schadow’s early interest in Dürer’s likeness, he undoubtedly paid careful attention to the most enigmatic of Dürer’s self-depictions, his iconic Christ-like image of 1500.

Having entered the Bavarian royal collections in 1805, the panel became instantly famous as the frontispiece of Johann Nepomuk Strixner’s pioneering reproductions of the artist’s “Christian-mythological drawings” (fig. 19).73 The lithographer had discovered the stunning marginalia, which introduced an entirely new, playful Dürer—the Dürer of fantasia—to a mesmerized public, in the Bavarian copy of a prayer book originally commissioned by the Emperor Maximilian in 1513 and adorned by various artists in 1514/1515.74 Resting his manly right hand with contemplative gravitas on his coat’s luxuriant trimming, the Renaissance master turns our attention back to the status-conscious, symbolically charged display of clothing, which had puzzled the original viewers of Schadow’s Bearded Man.

As Joseph Koerner has noted, fur played a crucial role in the construction of self in Dürer’s panel, which so boldly emulates the format of the icon.75 This conceit, the self-portrait as icon, rests on a strenuous exercise of control over self and image-making alike, which in turn exorcizes chance through radical frontality and unnatural symmetry. However, this proposition is immediately disturbed by the motif of the artist’s fingers fondling, as if unconsciously, the coat’s thick, soft lining. The motif of the small tuft of fur, pushed up between index and middle finger, adds an element of contingency, a haptic divergence from the hieratic order of the cult image with its demand of total visibility. At this instance, when the artist gives plasticity to the material reality of his touch, and at this place, where the sitter touches himself, the conjecture of the panel as a vera icon, as an acheiropoetic image “not made by human hands,” falters. “To imagine that the hand, resting against the sitter’s body, has unintentionally displaced the tuft of fur … gives us occasion to distinguish between Dürer as human sitter, idly fingering the fur of his coat as he tries to maintain a stiff pose, and Dürer as emblem of the imago Dei.”76 This dualism of embodiment and sacred geometry remained virulent, if toned down, when Strixner translated Dürer’s iconic self into pure contour.77

Schadow might not have picked up on the subtleties of Dürer’s play with different artistic modes; yet he probably sensed the ambivalence of Dürer’s embrace of fur. After all, for an artisan like Dürer, presenting himself in such a luxurious garment was a statement of status, a badge of wealth, power, and distinction far removed from the hairy shirts worn by the ascetic imitators of Christ.78 Schadow repeated this ultimately iconographic discrepancy. Yet beyond this play with legibility, Schadow must have felt a visceral attraction to the painting’s eloquent conversation between idealism and materialism, between the Christomorphic renunciation of madeness and the insistent manifestation of body and painterly craft. A symbol for Dürer’s bodily being—and as such an expression of carnal beauty, narcissism, and man’s proximity to beast—the touch of fur ultimately justifies the kind of Düsseldorf naturalist idealism that had brought Schadow into fiery conflict with his former brethren, above all with Johann Friedrich Overbeck and Peter Cornelius, who rejected his realism as sinful and evidence of artistic decline.79

Yet Schadow stood his ground. After all, he was convinced that a naïve return to the past was as impossible as it was undesirable, and instead pronounced a “circumspect innocence of manhood” as the attitude that “anyone with honest intentions” should strive for.80 Accordingly, Schadow gave a decidedly contemporary twist to his utterly Nazarene bow to the revered model of the past.

Political Landscapes

Ultimately, the modern aura of dress, etiquette, and scenery fully absorbs the historicism of the Bearded Man’s appearance and genealogy. The model becomes ennobled twice, from the representative, self-confident pose and the lavish, fur-trimmed wool coat, which wraps in such stately manner around the jacket’s soft, thick velvet, to the dual view of two castles and the relief of oak foliage on the pillar of the loggia, where Becker lingers so enigmatically. View and surrounding conjure up the period’s rampant Ruinenromantik (romanticism of ruins), which also holds the key to the picture’s interpretation. The portrait opens out from the depiction of an individual likeness to the vision of reconquering a lost ideal, to the idea of a birth, conceptualized here as a rebirth, of a unified national identity from the spirit of the Middle Ages and its Knighthood—in short, to the vision of a Deutschtum, of a Germanness or Germandom, that was as anachronistic as it was forward-looking. The picture summons the same kind of interdependency of reconstruction and recommencement, renewal and new beginning at play in Prince Friedrich’s Castle Rheinstein. One detail in particular embodies, pars pro toto, this emphatic interplay of past and present, nostalgia and renovation: Becker’s noteworthy beard, both emphatically fashionable and yet worthy of a Renaissance patrician (a beard that in the age of the hipster seems oddly contemporary once more). We will return to this hairy affair again at the end.

The reasons for Schadow’s approach are complex. They reflect not least the Düsseldorf artists’ claim to an advanced social standing, a claim that Schadow had systematically pursued since taking office and that was, in life as in Becker’s portrait, crowned with success. Already the picture’s formal severity, which aims for a monumental effect, and the solemn profundity of the sitter’s facial expression bestowed a historic aura upon the painting, an aura that ultimately justified its illustration in the aforementioned exhibition review of 1835 in the form of a wood engraving (fig. 12). This real-life interest was, of course, filtered through the broader question of ennobling the category of portraiture as such, and Schadow thus made every effort to preserve the picture’s interpretive openness. Consequently, he gave his audience very little to go on when it came to the sitter’s social background and professional occupation, and the fictive conversation of the visitors in the Hannoversche Kunstblätter cited at the opening of this essay testifies to the success of this strategy. Indeed, only the brash cap gestures clearly to Becker’s status as a painter; the tools of his trade, however, remain entirely absent. Perhaps one could read the veduta in the background as a reference, if a rather oblique one, to the lithographer’s panorama project. Yet this seems unlikely given the fact that this precise view was not part of F. C. Vogel’s printed route from Mainz to Koblenz. Instead, we see, probably from the perspective of Bad Honnef, the ruin of the castle Rolandseck with its famous Rolandsbogen and, opposite on the right river bank, the no less impressive Seven Mountains range (Siebengebirge) with the Drachenfels. Schadow thus chose a prospect that enjoyed great popularity among tourists and the producers of prints and postcards serving the appetites of this young industry.81 In contrast, the shimmering waters of the Rhine beneath the Rolandsbogen, which suggest that we stand on one of the small river islands, are artistic license. It seems more likely that the picturesque view captures the perspective from one of the villas that increasingly populated the hillside of the Rhine’s left bank.82

Schadow’s nod toward modern travel gives the picture an emphatically contemporary note, which is, however, immediately tempered by a resounding chord from the past. As the scenery’s picturesque allure tempts us to give into the pure enjoyment of a Sunday boat trip, the figure’s somber grandeur reminds us that history is calling us to restore the glory of our medieval ancestry. As memories of times long gone are awakened, so are literary allusions, and for a moment we seem to face not only an unknown painter but also Friedrich or Leontin, the heroes from Joseph von Eichendorff’s 1815 novel Presentiment and Presence, as “they emerged from the woods and stepped upon a projecting rock, [and] suddenly saw coming from the miraculous far away distance, from old fortresses and eternal forests the stream of ages past … the royal river Rhine.”83 Many among Schadow’s audience would have been familiar with this enchanted novel about Germanness, the War of Liberation, and the longing for the land where one belongs, for our Heimat. Most importantly, in novel and painting alike, the river not only conveys, or alludes to, but actually is history. The lack of a clearly defined location turns into a metaphor for the need to dive, like Eichendorff’s protagonists, into the Rhine as a way of enacting and expressing our commitment to (of leaping into) German history.

Schadow’s reluctance to depict local backgrounds, and his even greater reluctance to depict explicitly German ones, leaves no doubt that the picturesque and well-known landscape unfolding in his 1832 portrait reiterates the previous avowal of Prussia to the Rhineland, or more aptly, the avowal of a Prussian Rhineland that he had articulated two years earlier in the double portrait of the Hohenzollern princes (fig. 8). Yet this reiteration undergoes a profound change, as it gains evocative power and interpretive openness at the cost of iconographic ambiguity. Indeed, a nostalgic atmosphere permeates the patriotism of the Romantic evocation of the Rhine and its castles, a wistfulness that inevitably (although not necessarily intentionally) adds ambiguity to the picture’s political meaning. This sense of multivalence only increases when one realizes that in 1832 Jacob Becker would participate in the Hambach Festival, a mass rally at a castle in the present-day Rhineland-Palatinate, where as many as 30,000 liberals and radicals gathered to demand constitutional rights, freedom of the press, and national unity. In these last days of May 1832, thousands upon thousands of farmers and day laborers, artisans, and students from throughout Germany would march under the German tricolor of black-red-yellow (the latter heraldic “gold”), Becker among them. Although not a call to revolution, this articulation of liberal and republican oppositional viewpoints still alarmed conservative forces, which feared the imminent danger of insurgency.84 Ultimately, this “national festival of the Germans” left no indelible marks on the life and work of the future painter. Nonetheless, it throws into relief the interpretive openness of the Rhine nostalgia so prominent in The Bearded Man. Needless to say, Schadow would have vehemently denied such national-democratic inflections, which he would have seen as an attack on the monarchy he devoutly served. Yet the painting develops a momentum of its own, which, defying Schadow’s desire to control the picture’s signification, recalls the polyvalence of the Mourning Royal Couple by his student Carl Friedrich Lessing (fig. 20). A sensation when first shown at the exhibition of the Berlin Academy in 1830, the canvas astonishes through its ability to support radically divergent readings, ranging from republican, antifeudal, and antimonarchical interpretations to an enthusiastic reception in conservative circles, which clearly saw here, as its buyer, the reactionary Russian Imperial Family, a declaration of alliance to the dying monarchy.85 In Lessing’s case, such ambiguity was programmatic. In Schadow’s case, it was not. Probably not even intended, the canvas’s potential multivalence rather speaks to the somewhat untamable momentum gained by the reform of historical representation in the Düsseldorf Academy. Creating new expectations and new modes of reception that empowered viewers, as Cornelius Gurlitt observed in 1899, “to pluck stories from the paintings” and concern “themselves not only with what was represented, but … with the most extensive spiritual associations,” the new history painting inevitably shaped Schadow’s own work.86 Whether intended or not, it was precisely this momentum that made the academy director’s concern with a notion of Germanness so relevant and his proposition of a German national character wrested from the remnants of the Middle Ages so befitting for a broad audience.

Portraiture into History

The look across the Rhine to France highlights the significance of Schadow’s intervention as an attempt to elevate portraiture to a meta-genre, which would be capable of suturing the rift between different forms of historical imagination, representation, and pictorial realization. Despite the battles with his former St. Luke brethren, Schadow remained indebted to his Nazarene origins and hence wanted to ground this operation, as well as his idealist naturalism at large, in Christian doctrine. On a stylistic level, he answered this desire with a powerful theory of painting as incarnation, as “The Word Made Flesh.”87 When it came to history painting, however, he pursued a different strategy and located its modern source in portraiture. He arrived at this position via the sensuous renewal of art in the early Christian period. With the mosaics of the fifth and sixth centuries in mind, Schadow declared in 1842 that the rejuvenation of art after antiquity’s decline originated “from the head and its physiognomic expression” or, to put it differently, from the countenance, not the body.88 This, in turn, allowed him to make portraiture the mediating principle between the era’s competing modes of historical representation. In the process the portrait became, both in theory and in the curriculum of the Düsseldorf Academy, the precondition of historical painting and, in its capacity as an independent undertaking, embodied the school’s poetic—or, perhaps more aptly, poeticizing—principle.

Not surprisingly, Schadow’s remodeling of history painting reflected back on the genre it evoked, portraiture. Inverting his notion of naturalist idealism as the basis for grand histories, he called for an idealist naturalism in the lower genre, whether likeness or landscape. His basic rule was that the portraitist had to poeticize and thus ennoble the sitter by capturing the model’s essence and inner ideal, instead of producing a sort of common Steckbrief, a “most-wanted poster.”89 Schadow’s strategies for achieving this goal were simple but effective. He largely shunned the trappings of social prestige in favor of simplified, introverted compositions in which a hint of abstraction added a Nazarene touch. Frequently, he assimilated religious prototypes, which, aided by a judicious choice of dress, attributes, and symbolic colors, helped to intimate spiritual subtexts, moral values, or allegorical meaning.

Before portraiture could metamorphose into a historical genre, however, it had to be freed from the sitters’ whimsies. For portraiture to be history, it had to free itself from its commercial shackles, from the strictures of the patrons’ self-image and vain demands. In the 1830s, Schadow thus painted a series of likenesses, many of them begun during his second voyage to Italy from 1830 to 1831, which translated his investment in symbolically charged portraiture into the production of autonomous works.90 Critics immediately took note.

In his 1839 account Die Düsseldorfer Malerschule (The Düsseldorf School of Painting), the left-leaning journalist and art critic Hermann Püttmann, who would later become a founding father of the German press in Australia, invented a special category for Schadow’s fusion of ideal types and observation of nature: the “costume or portrait genre.”91 The critic was particularly smitten with Schadow’s likenesses, which he perceived as “free inventions” that responded to artistic considerations alone and not the distorting demands of a meddling patron. As such, Püttmann gushed, they were unspoiled by debasing pecuniary interests and, in contrast to the despicable “copies of everyday faces,” rose high above the “day-laborer productions” of common portraiture.92 These debates underscore the emphatically programmatic nature of The Bearded Man and the necessity that the portrait remained in Schadow’s studio as a completely independent product of his imagination. Indeed, The Prince’s infusion of the monumental royal tondo with elements of the genre historique seems to respond not merely to Schadow’s desire to reform the tired format of the monarchical state portrait, but also to his aim to free what was de facto a rather prestigious commission from the bad odor of intrusive patronage and manipulation. In this sense, the psychological rendition of the two Hohenzollern and the genuinely Romantic inwardness of the princely general mark the areas of “free invention,” of artistic control and purely aesthetic deliberations so important to the transformation of portraiture into history. Of course, Püttmann’s idea that any work could transcend market concerns was wishful thinking, and in fact Schadow paid careful attention to economic matters in his own professional life and that of his students. Yet the critic’s attitude is an important articulation of the anticommercial undercurrent that had shaped the Brotherhood of St. Luke from the beginning and remained a signifier of true art in Düsseldorf.