Beginning on March 23, 1987, Calvin, of Bill Watterson’s comic strip, Calvin and Hobbes, appeared with a simple cardboard box that Calvin called the “transmogrifier.” The transmogrifier can transform Calvin into anything; it is also a time machine and a space ship. The empty cardboard box holds limitless potential. It is big enough for small and medium-scaled objects, including the toy-sized tiger, Hobbes. Because the box can contain any one thing of a certain size, the transmogrifier can imaginarily contain any other thing of the same or smaller size; its gestalt making the magical transformation possible. Equally importantly, by moving things in space the box effects a link to anywhere and anytime, which is how the transmogrifier enables time travel in Calvin’s world. When one transmogrifier breaks down, the reader and Calvin both rightly assume he will find another discarded cardboard box somewhere nearby to take its place. Over and again in the comic strip, Calvin works the magic of his imaginary machine. The adaptability of the manufactured box as a container for myriad things, its portability to many places over time, and the ubiquity of the box, are the most salient characteristics of Calvin’s beloved transmogrifier. These are also the three most salient features of commercial containers, at whatever scale, since containers circulate all manner of things to all manner of place in the modern manufacturing and distribution system.

Containers have become something of an obsession of mine, which means I see them everywhere and return to them again and again when thinking about art, or in this case, art criticism. From the time of its invention in the middle 19th century, the manufactured box gradually became a widely adopted form in both consumer and art culture, the box giving material form to the homogenization of three dimensional space shaped by industrial manufacture.1 There were, to be sure, plenty of cardboard and other cheaply made boxes in American life before the middle twentieth century, but after WWII this trickle of boxes through American households became an inundation. The floodgates for this tsunami of packaging were opened by the invention of container shipping after WWII, which allowed for the expansion of global trade and shipping by road, boat and rail. “The value of this utilitarian object lies not in what it is,” according to finance journalist Marc Levinson, “but in how it is used. The container is at the core of a highly automated system for moving goods from anywhere, to anywhere, with a minimum of cost and complication.”2 The process is familiar; an object is packaged in a retail box, which goes into a wholesale crate, which goes into a shipping container, which travels by truck, train or transport ship across continent or ocean, to a distribution center where, in an unpacking of the shipping container to crate to box to thing, it finally enters the home or office, and in so doing kicks off another transmogrifier for Calvin and his imaginary friend. The box in this scenario is sufficiently open-ended (so to speak) that it inspires imaginary play. In Calvin’s world, the box is at the center of his utopian child’s world. In the last ten years or so, container architecture had proliferated across the human landscape – not in the modernist form of Corbu’s idealized containers for living, but in the form of actual shipping containers adapted as hotel rooms, refugee housing, and house additions.

Malvina Reynolds’ popular song, “Little Boxes,” of 1962 links virtually all aspects of American mainstream culture of its moment to the manufactured box in terms that resonate with a completely negative reading of the manufactured box and its scaling up to the mass produced housing of that time (and in anticipation of today). 3 In contrast to the playful, imaginative transmogrifier of Calvin and Hobbes, Reynolds’s famous description of the houses in Daly City (just South of San Francisco, California) reversed the terms as the people subject to the proliferating logic of container culture were depicted as becoming uniform like the boxes. Homes took the form of a container; “Little boxes on the hillside, little boxes made of ticky tacky, little boxes on the hillside, little boxes all the same.” These were containers made for mass produced people; “and the people in the houses all went to the university, where they were put in boxes and they came out all the same.”

From the widespread use of television sets (the idiot box) to skyscraper architecture (containers for living), to Levittown, NY and places like it (“Little boxes on the hillside”), and the well-stocked shelves of American stores (from TV dinners to home and office supplies), boxes of all kinds and scales have proliferated from post WWII America through the present.4 That this proliferation has its domineering aspect is no doubt implied in the present by that most muscle-bound image of feminized container culture, the “Amazon.”

Objecthood and the Empty Container

This is the polarizing view of containers that I had in mind when, a few months ago, I picked up Michael Fried’s 1967 article, “Art and Objecthood,” and reread it with the benefit of fifty years hindsight. I was immediately struck by the aptness of reading it alongside the pairing of Calvin and Hobbes’s transmogrifier and Malvina Reynolds’s little boxes, which utopian and dystopian view of their respective containers tracks almost perfectly alongside the voices speaking in defense and criticism of Minimalism, or more properly Literalism, in Fried’s benchmark article — the artists affirming the adaptive and performative potential of the blank form, and Fried lamenting its standardizing, normative affect. It stands to reason that this association would have struck both the artists and the critic as bizarre, since they were engaged in making art and writing about it. But it is clear to me, and I hope to argue persuasively, that the arguments for and against containers in the arts are neither remote from nor separable from the appearance of containers in the cultural mainstream, as the various authors at the time would understandably have assumed.

In the post-war New York artworld, ambitious painting was widely described metaphorically and physically through the language of its progressive flatness (as theorized by Clement Greenberg), meaning it had less and less to do with the illusionistic worlds seen inside the perspective box (a theatrical stage of sorts), and a lot to do with the material support of the work. For painters, this logic had gone about as far as it could with regard to flatness, but the shape of painting (and sculpture) had been virtually neglected by artist and critic alike. Fried took up the issue immediately prior to writing “Art and Objecthood.” In “Shape as Form: Frank Sella’s Irregular Polygons,” for example, Fried described Anthony Caro as making work in which “The individual elements bestow significance on one another precisely by virtue of their juxtaposition,” 5 which means the internal elements are directed toward each other and achieve a certain completeness by virtue of their relationality within the artwork. When shape is form in a successful work, by this account, the work is experienced as full, complete; a successful sculpture is experienced as separate from the rest of the world because it is formally self-sufficient. It contains nothing but itself, because the shape demands it.

The problem with Minimalism in Fried’s account was that it rejected the productive friction between depicted and literal form, resulting in an empty box; “shape that must belong to painting,” he writes, “—it must be pictorial and not, or not merely, literal.”6 Donald Judd, Robert Morris, and Tony Smith (among others) were described as rendering in three dimensions what had been the dialectical force of painterly modernism between the mark and the materiality of the object (not necessarily, indeed by 1967 not only, the surface). Fried’s emphasis on the fullness of work framed by shape is the basis for his critique that the Minimalists had effectively reversed Clement Greenberg’s 1954 proclamation that “pictorial space has lost its ‘inside’ and become all ‘outside’”7 by making work in which pictorial space had lost its ‘outside’ (nothing is outside the artwork) and become all ‘inside’ in the sense that anything and any situation can be placed (materially or visually) in art conceived as a container.

Because these artists created forms that opened up to the world, in other words, literalist work would be ‘shapeless’ in the sense that the form was not adequately self-sufficient to create an experience for the viewer as a discreet artwork. Instead, in Minimalism there is nothing there, or not enough for the object to rise to the level of good art. Literalists effectively framed and directed attention within the world, the artwork becoming essentially a container for any-and-everything. Nature abhors a vacuum, as the saying goes, so this ontologically shapeless, functionally empty container in effects sucks up the world and human attention alike.

Bracketing the various positions for and against Fried (which are not especially interesting to me), his commitment to experiential fullness and ontological shape raises useful questions with regard to the effects of container culture on the arts. Bluntly…Is anything left out? Does containerization in art demonstrate the extent to which anything can be subject to the manufacture/distribution logic of container culture generally? Is container culture the same thing as commodity culture? Why does it matter, or doesn’t it? One can imagine the conversation between Calvin and Hobbes as occurring between a Minimalist artist engaging with an emerging culture of performativity and a critic. Calvin: “You step into this chamber, set the appropriate dials, and it turns you into whatever you’d like to be.” Hobbes, “it’s amazing what they do with corrugated cardboard these days.” To which the modernist critic might object, as Fried does in “Art and Objecthood,” “all that matters is whether or not a given work is able to elicit and sustain (his) interest.”8

The universalizing language of hollowness and objecthood appears repeatedly in the writing by the artists. For example, Donald Judd’s 1965 essay, “specific objects,” describes three dimensionality as a universal (instead of particular or unique) vessel (which Judd calls a container).9

Three-dimensionality is not as near being simply a container as painting and sculpture have seemed to be, but it tends to that. But now paint and sculpture are less neutral, less containers, more defined, not undeniable and unavoidable. They are particular forms circumscribed after all, producing fairly definite qualities. Much of the motivation in the new work is to get clear of these forms. The use of three dimensions is an obvious alternative. It opens to anything…Three dimensions are real space.10

As described here, Modernist painting and sculpture had (“now” in 1965) established too clear boundaries on what was possible for ambitious artists, they had lost their creative capaciousness, their apparent neutrality as media for all manner of work. At an earlier time these established media (painting and sculpture) “seemed to be” “simply a container” that could hold a wider range of experiences. But that neutrality, or openness, has been compromised, presumably by the disciplinary limits of orthodox modernism (“they are particular forms circumscribed after all, producing fairly definite qualities” such as flatness, surface emphasis or an emphasis on shape). Three dimensionality, however, while “tending” to be a container in the positive sense of giving artistic production stakes, avoids these constraints because, like an actual box, “It opens to anything…Three dimensions are real space.” This is a container Judd can live with because of its neutrality, because it is not experientially full. Like the transmogrifier, three dimensions can contain anything, anywhere, and at anytime.

Hollowness, in Fried, works just this way – it is a function the literal emptiness of the container and the blurred edge of the artwork – the place where the object surface both delineates the edge of the material while also opening up to the world around it and (by extension) pulling that world into itself. Ontological hollowness is negative for the Friedian beholder in the sense that the work has the qualities of both an artwork and whatever is near at hand that it engages relationally. Looking through a Judd, I see a chair, or a shadow on the wall, or (when scaled up) a building, Texas landscape, or another human being. By virtue of its hungry emptiness, the work confuses the ontological categories of art and life, producing, for Fried, an oppressive mashup where the life of the form and the life of the person equate to one another. Even if the artist or viewer feels liberated by the apparent openness of possible interactions, as in Judd’s above account, in Fried’s account this beholder is, in fact, trapped in a telescoping world of proliferating objects in shapeless spaces, in object-hoods. He writes “[T]he apparent hollowness of most literalist work – the quality of having an inside – is almost blatantly anthropomorphic. It is, as numerous commentators have remarked approvingly, as though the work in question has an inner, even secret, life…”11 These container artworks, in other words, have a certain power, a ‘secret life’ by Fried’s account, which contradicts their apparently abstract form and which, despite arguments to the contrary, oppresses the formal imagination.

Reading Fried’s lament against Malvina Reynold’s’ song, the line “And the people in the boxes all went to the university, were they were put in boxes and they all came out the same” recalls his reading of Tony Smith’s 1962 piece Die, for example, the famous steel cube of 6’ on each side. Fried describes that “One way of describing what Smith was making might be something like a surrogate person – that is, a kind of statue.”12 Interacting with Die asserts an insistent fluttering across surface/edge, subject/object, person/thing, now/then boundaries. It is as if the box contained the person: [person], or, rather the presence of the uniform person, […], conceived as normalized to fit into the box’s homogenizing form as a human surrogate. This capturing of the human-presence-in-absence requires a universe conceived as a unitary space, a simple and coextensive geometry of lines, planes and cubes from which every aspect of the world we live in is carved out (maybe suspended is more accurate) and geometrically measured relative to ourselves.

This world is necessarily serial in nature, as its Cartesian nature means that the idealized geometry is universalizing. When Fried quotes Judd writing, “the big problem is that anything that is not absolutely plain begins to have parts in some way,” he is describing Judd’s idealism, a world in which perceptible parts constitute a wrinkle or flaw in a cosmic geometry of omnipresent flow.13 Fried responds: “The shape is the object; at any rate, what secures the wholeness of the object is the singleness of the shape.”14 The shape is the object in the everyday language of containers as well. When a package arrives (no matter the scale), the habitual response is, “the books,” “the toy,” “the _____,” has arrived. The casual comment demonstrates the extent to which the shape (or the ontological shapelessness) of the container becomes equivocal to the thing inside it, carving out (as it does), objects from the homogenized, three dimensional cube that would circumscribe whatever the container contains. This fundamentally Cartesian logic, a geometric cube-system in three dimensions, also establishes the continuity between that unitary form and the entire world of distribution and manufacture around it. Fried quotes Morris on this point, writing: “Morris believes that this awareness is heightened by ‘the strength of the constant, known shape, the gestalt.”15 In other words, this unitary form is precisely why the work functions as an inexhaustible frame, since the world of things is infinite with the Minimalist gestalt or shape imposing a limiting awareness. Fried, rejects the logic, however, using the language of empty containers in the negative, writing “It is inexhaustible, however, not because of any fullness – that is the inexhaustibility of art – but because there is nothing there to exhaust.”16

The Neighborhood of Objecthood

The preceding examination of Fried’s argument in terms of the hollow form of containers does very little to explain why artists were engaged with the form to begin with, however that history is arguably close at hand. Because of the advent of container shipping after WWII, by the middle 1950s lower Manhattan was losing its status as an international manufacturing and distribution hub for consumer goods. Most spectacularly, SoHo factories were shuttering up and moving elsewhere; its side streets were simply too narrow for trucks pulling shipping containers. In the wake of this industrial flight, the abandoned factory buildings stood like dark, specter-kings lording over the no-longer-necessary, abandoned piers and loading docks of the Hudson River.17 The arson-prone neighborhood was called “Hell’s Hundred Acres.” Streetlights were turned off at night. There was virtually no traffic. No stores. Few restaurants. A bar or two for a dwindling community of workers. The container, by this reading, produced distribution efficiencies that fueled almost unparalleled economic growth, but in so doing brought an aging infrastructure and a New York neighborhood to its knees.

In SoHo, these abandoned factories and industrial remnants were available, at virtually no cost, to a handful of artists who began living in these lofts in the late 1950s. As described by painter, Chuck Close, with some hyperbole, “SoHo barely existed when I moved there in ’67. There were maybe 10 people living between Canal and Houston…rats were running everywhere.”18 Factories vacated by the arrival of containers were empty, in his account, forming a kind of urban vacuum awaiting the next occupants, the rats signifying urban decay and the artists, renewal. The description gives pause, or should, despite its being ten years late on when artists actually began moving in. Among the early arrivals were the dancer, Simone Forti, and the sculptor, Robert Morris. Forti’s 1960/61 “dance constructions” were instructional works consisting of free movements (circumscribed by instructional “rule games”) specifically linked to the environment (the abandoned industrial spaces) where these works were realized. Dancers might be found balancing together or walking among others standing on ropes looped from the industrially scaled ceiling (hangers, 1961), or seen trying to navigate (using knotted ropes) across a piece of plywood leaning steep on the wall (slant board, 1961). These works used materials left behind in the industrial spaces, while also integrating the characteristic high ceilings and open feel of the abandoned factory. One 1960 ‘dance construction’ is especially literal when it comes to the neighborly relationship between the SoHo loft and the proliferation of boxes in art. Roller Boxes (1960) was performed at the Reuben Gallery, a loft in SoHo. At that performance, two performers in leftover wooden crates on rollers were pulled across the floor. The performers, Patti Oldenberg (wife of the Pop artist, Claes Oldenberg), and Forti were pulled around the gallery on ropes.

The activation of the space using the materials and forms left behind by light manufacturing would have an enormous influence of Forti’s husband, the sculptor Robert Morris, who plays such a pivotal role in “Art and Objecthood.” In a 1994 interview with WJT Mitchell, Morris is explicit about the importance of Forti’s word-based, instructional, action-framing/generating approach to dance, called ‘rule games,’ and her influence on him with regard to the exploration of how objects and the spaces they form generate movement:

As to influence, Marcel Duchamp is obvious. Less obvious perhaps was my first wife, Simone Forti, who set the agenda for the Judson group–rule games, task performances, the use of objects to generate movement, the use of text in performance.19

Morris’s large-scale 1961/2 L beam-forms, his passageway, his planks and his box shapes display clearly Forti’s influence on her husband. Morris’s forms bend the body of the beholder, who moves around them as one might navigate a space left in a hurry by a closing factory, or at the very least shaped by such an experience. In the 1994 SoHo Guggenheim exhibition that immediately followed this interview, “The Mind Body Problem,” viewers could be seen in all manner of physical interaction with the works. Strangely, visitors are completely absent from the installation shots. A crisper demonstration of the relationship between the industrial forms of the lofts spaces and the body in Morris’s work would be found in his 1964 performance piece, “SITE,” in which the performance artist, Carolee Schneeman posed on a couch as Manet’s Olympia while Morris, dressed as a workman, moved large, plywood sheets throughout the space first disclosing, then concealing, Schneeman.20

I have used Forti and Morris as paradigmatic for the way some artists responded to the loft environment, not to say that’s all there is, but in order to demonstrate the possible integration of a few key aspects of the work environment of these artists into a more generalizable sensibility that inheres in the container. Clearly, SoHo’s founding artists engaged with the container as more than a mere box in the industrial sense, transforming it into a frame, a locus of instruction, a staging of movement, a mechanism for audience transformation, and a means of connecting to the environment. Forti’s and Morris’s creative world was a world of critical exploration, of experimentation, of games and rule games, and engagement with the materials and circumstances at hand. SoHo’s founding artists, to put it briefly with Forti and Morris as paradigmatic, would be on the Calvin and Hobbes side of what the container offered them at every scale.

The later explosion of real estate values in SoHo was unimaginable to these artists, who sought simply low rent and distance from the commercial art world and most of whom were (in any case) eventually priced out of the neighborhood. As far as the general public and city officials were concerned, however, artists in SoHo at the time were a negligible subset of beatniks and hippies. Living in theses abandoned spaces was illegal. By the middle 1960s, SoHo was slated for destruction by the urban planner, Robert Moses, who envisioned an industrial corridor running across Manhattan at SoHo, which would be reshaped by a highway built for, what else?, container trucks framed by subsidized high rises and factories shaped around the industrial container form. Moses had successfully built housing for artists in a planned community in nearby Westbeth, and was widely admired for building Lincoln Center, so he had reason to consider himself someone working on the side of artists even as the SoHo project, which would have destroyed an organically evolving artists’ colony, seemed likely to move forward.21 The first phase of this public housing project was constructed at the East end of Canal Street, where the buildings stand today in their unabashedly ugly, functionalist glory. In contrast to this planned manufacturing-and-housing scheme, artists in SoHo pushed back, inventing the live-work loft space and alternative (for the time) gallery system. “There were no subdivisions in our life,” wrote Twyla Tharp about SoHo in the early days, “We did not leave to go to work: that would have been bourgeois.”22

In his history of SoHo, Richard Kostelanetz summarized this shift in terms that speak directly to the shift in how artists described their work as linked to a formally and geographically shifting art world. Describing Soho’s artists, Kostelanetz writes:

The key word in defining their culture was ‘downtown,’ which was meant to distinguish the SoHo world from ‘uptown,’ which was everything north of Houston Street to some or 14th Street or 23rd Street to others. From big things to small, downtown was different. Even certain words were used differently downtown…when a SoHo artist spoke of ‘work,’ he meant his art. A ‘job’ is what he or she did for money, usually uptown, if not farther elsewhere…The epithet ‘downtown’ identified distinctly alternative styles not only in visual art but also in theater, performance art, dance, and even literary writing.23

This terminological shift, from making art to making work (as in Forti’s making ‘constructions’), was widespread. The idea for the downtown artist was to bracket, however temporarily and provisionally, whatever the artists of the downtown scene were doing from the norms of the commercial galleries uptown, which were widely associated with professionalized Modernism.

This reorientation in art making and living is described similarly by Helen Molesworth, in her description of SoHo in Work Ethic.

Wildly different in scale and effect than the garret apartments of prewar artists, loft spaces were typically abandoned light manufacturing buildings…One unique quality of SoHo was that artists from disparate artistic movements lived and worked their simultaneously. Stella occupied a loft space on West Broadway in 1958, and Alison Knowles and George Maciunas, both Fluxus artists, were some of the first artists to buy buildings in SoHo [actually Alison’s was a rental at Canal and Broadway, where I was born]. Allan Kaprow’s Happenings took place in SoHo lofts; artists involved in the new sculpture (Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Richard Serra) lived and worked there, as did Conceptual artists (Sol LeWitt and Mel Bochner). This highly abbreviated list suggests that no matter how divergent their aesthetic concerns and practices, the infrastructure of SoHo was a common denominator in putting pressure on artists to perform or stage their work in new ways.24

In other words, the collapse of light manufacturing and the abandoned boxes, industrial materials and machines had an explicit and demonstrable effect on artists. This infrastructure had its basis in the manufacturing sector. Using the materials of their environment, in summary, meant that these artists invented a form of art-magic of the container.

The ever-evolving spatial logic of the box is (by definition) inseparable from the experience of time, just as the consumer container is necessarily part of a system (a logistical system) that includes other containers caught in an unfolding process of production and consumption. The sequencing of Minimalist forms, “one thing after another,” in Judd’s terms, identifies the container with time. Even scaled up minimalism works this way. They can be seen as a row of empty boxes, shapeless objects in Fried’s sense, laid out in a row as a rarified assembly line of voids awaiting person, place or thing. Fried again, “the experience in question persists in time, and the presentment of endlessness that, I have been claiming, is central to literalist art and theory is essentially a presentment of endless or indefinite duration.”25

Duration, for the Modernists, more properly belongs to poetry and music, which is why the dimension-hopping aspect of Minimalist art between two (flat), three (space), and four (temporal) dimensions predisposed the work to theatricality since “what lies between the arts is theater.”26 The influence of the American composer, John Cage, across the arts can be seen as particularly offensive to this framework. Not surprisingly, Cage’s most influential piece, 4’33” of ‘silence,’ could easily be described as transforming music into an open container for sound.

In other words, the theatricality of Minimalism for Fried had only partially to do with the effect of the hungry void, the container, on a beholder who frame-shifts and body shifts in relationship to the unitary forms of a Calvin and Hobbesian experience. But the problem is not embodiment per se, as might be supposed. Fried allows for embodied knowledge among Modernist sculptors, including especially Caro, who are “possessed by the knowledge of the human body and how, in innumerable ways and moods, it makes meaning.”27 Significantly, however, for the Modernist sculptor to succeed, s/he would necessarily bracket self-conscious awareness of the passage of time. This is what Fried is emphasizing when he writes that “The literalist preoccupation with time – more precisely, with the duration of the experience—is, I suggest paradigmatically theatrical.”28 Theatrical, here, refers to the pulse, the sequencing, the tethering of actions and objects to their situatedness in a temporal sequence (how like a manufacturing process the account is!) which is intrinsic to virtually all art of the era.

American philosopher, John Dewey, was widely read at the time by artists and describes aesthetic experience as emphatically time dependent: “All interactions that effect stability and order in the whirling flux of change are rhythms.”29 These rhythms are known both through the body and mind, which is why Dewey placed a multi-sensory pedagogically informed aesthetics at the center of his educational program. Dewey means that patterns or systems of cultural production and analysis produce sensitivities in the human animal that interact with the changing nature of the world (physical, natural, and social) perceived by the senses. The perceptual pattern established between perceived system and non-system constitutes the core of the rhythmic basis of aesthetic experience for Dewey, whether in the domain of nature or culture. Significantly, Dewey’s description of aesthetic experience as inherently rhythmic means that experience itself is bound to the human perception of time.

Fried, in contrast, critiques the artists using experience using the language of interest: “The experience alone is what matters,” for Literalism. He continues, describing experience as triggered by interest.

For Judd, as for literalist sensibility generally, all that matters is whether or not a given work is able to elicit and sustain (his) interest. Whereas within the modernist arts nothing short of conviction – specifically the conviction that a particular painting or sculpture or poem or piece of music can or cannot support comparison with past work within that art whose quality is not in doubt – matters at all.30

Interest/experience and conviction suggest opposing terms for what good art means in terms that implicity challenge the values of the container. The container, borrowing from Fried’s logic, resists conviction by bracketing the issue of material or formal conviction relative to modernism. On the other hand, it would seem we have an aesthetic system being introduced by the artists of the 1960s that, following Dewey, trains the human being for an evolving sensory world, art (by this description) assisting the human being in establishing each beholder’s place in a complex and changing social and physical environment modeled on the container (Calvin and Hobbes). On one side, we have a Modernist aesthetic system tasked with establishing conviction, with developing a particular (particularly critical) formula at the level of every medium evolving independent of the surrounding art and general culture. This is what critical distance means.

While I might differ with Fried on which movement executes the task of culture more effectively (are we better served by sensory attunement or critical distance?), he rightly identifies in his evaluation of Minimalism a persistent problematic of the time with regard to how work does or does not open up to its world. Dewey’s distinction between good and bad, socially expansive or contracting experiences that become so for reasons beyond mere interest, suggests there is a viable aesthetic position that utilizes interest to establish commitment. At its worst, in other words, the generalization of interest functions like the absorptive experiences that comingle with the entertainment spectacle of mass culture and Fried is right to mark that risk as real. Another way to say this would be that, because anything can go into the hollow container, and because these link one-thing-after-another, the Minimalist artwork can be described (at its worst and under certain conditions) as a near perfect cypher for the container’s homogenizing power, which power is in itself an amplification of the power of the individual commodity object.

From the perspective of containerization, in other words, interest and spectacle are mutually dependent terms engaging an increasingly lazy imagination. While acknowledging the rightness of Fried’s core objection (which is so glaringly obvious in so much contemporary neo-Minimalist or massively-scaled Minimalist art) however, John Dewey is useful for differentiating types of experience at the level of interest. Dewey makes a distinction between mere experience and cumulative experience: the one is essentially synonymous with spectacle and the other with educative and positively socializing experience. On the topic of experience and education, Dewey writes:

Each experience may be lively, vivid, and “interesting,” and yet their disconnectedness may artificially generate dispersive, disintegrated, centrifugal habits. The consequence of formation of such habits is inability to control future experiences. They are then taken, either by way of enjoyment or discontent and revolt, just as they come.31

We (me, many friends in the art world) have been trained to see, for example, the massive containers of Judd’s Marfa as emblematic of a universal form tuned elegantly to the planar forms and mineral colors of the desert Southwest, but also the playful, kid-friendly sculpture gardens of ultra-elite museums, not to mention the neat scaling down of the box-forms to the table-tops of lucky collectors. But Judd’s scaled up boxes could also be seen as tuning their audience to the visual pleasures of debris field and commodity alike – as amplifiers of the immersive sensation of the commodity fetish. This is what Fried means when, toward the close of “Art and Objecthood” he claims that “it is by virtue of their presentness and instantaneousness that modernist painting and sculpture defeat theater,”32 meaning the spectacular versions of everyday life at every scale.

Bracketing the evaluative aspect of “Art and Objecthood” about which so much ink has been spilled, this axis (interest and the commodity) suggests that there are aspects of Fried’s framework that can be productively deployed in terms of a critical perspective on an emerging, widespread container culture at the moment when the piece was written. Each aspect of Literalism/Minimalism described by Fried can, in summary, be used to describe the shipping containers and manufactured boxes of the era, which are shapeless, hollow, designed for seriality, and performative in terms of the behavior they elicit from the beholder. His critique, if extrapolated beyond the artworld, speaks volumes to the subsequent acculturation of the laborer, or, in the home, the consumer. In addition, Fried’s criticism of Minimalism as literal, offers a useful account of container culture that challenges the artist and art historian alike to move beyond the habitually celebratory accounts of ‘the everyday’ and ‘play’ as inherently and always liberating.

In thinking about containers while reading “Art and Objecthood,” Barbara Rose’s 1965 essay “ABC Art” is likewise paradigmatic for the precision with which it identified the container as expressing a generalizable experience of the time in a specific neighborhood.33 The question is what kind of experience is being described?

Judd’s latest sculptures, for example, are wall reliefs made of a transverse metal rod from which are suspended, at regular intervals, identical bar or box units…Morris’s four identical mirrored boxes, which were so elusive that they appeared literally transparent, and his recent L-shape plywood pieces were demonstrations of both variability and interchangeability in the use of standard units. To find variety in repetition where only the nuance alters seems more and more to interest artists, perhaps in reacting to the increasing uniformity of the environment and repetitiveness of a circumscribed experience. Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes, silkscreen paintings of the same image repeated countless times, and films in which people or things hardly move are illustrations of the kind of life situations many ordinary people will face or face already.34

Judd’s “box units,” Morris’s abstract, spatial “standard units,” and both the form and labels of Warhol’s Brillo Boxes together express “the increasing uniformity of the environment and repetitiveness of a circumscribed experience” of ordinary people at the time – the experience of mass produced, ordinary, people. Repetitive, standardized, and reacting to the “uniformity of the environment and the repetitiveness of a circumscribed experience,” Rose articulated the social features of container culture “as illustrations of the kind of life situations many ordinary people will face or face already.” Elsewhere, Rose expands the domain of the box within art by including the instructional nature of Judson Dance and the musical containers of composer John Cage, which would include his students in Fluxus, who invented the reduced means, instructional performance “Event” and the small boxes of industrial cast-offs associated with the Fluxkit. By contextualizing box forms and life situations, Rose is implicitly linking the work to the culture of containerization as I’ve laid it out. Significantly, the issue is not whether the work affirms or critiques those ‘life situations,’ but rather that the work tunes the user to them.

Clearly, the many art movements of the era and time in New York (Pop, Minimalism, Fluxus and Happenings, for example) can be differentiated (and have been) with regard to their making work that affirms, criticizes, or brackets a seemingly ever-expanding, container culture. Clearly, the prevalence of actual manufactured boxes in all of these movements suggests that the container is a leitmotif of a period style in art that encompasses them all. When Barbara Rose writes that “To find variety in repetition where only the nuance alters seems more and more to interest artists,” she makes the connection between the box forms in visual art and the world at large, continuing in terms that establish motive, “perhaps in reacting to the increasing uniformity of the environment and repetitiveness of a circumscribed experience.” Container art, by this account, enables creativity and therefore forms of free play inherent in the environment of Reynolds’s ‘ticky-tacky’ container homes and people. Calvin and Hobbes can be imagined as hanging out in a back yard of just such ‘little box’ and being lulled into thinking they have created something meaningful.

Like the Minimalist object, Warhol’s boxes are adamantly empty; the silkscreen ink spread taut and flat across each plywood box surface, which box the viewer knows is empty because it is made of plywood, not cardboard as the real one would be. The container, in this case, is all about its outside, its label, which partially links it to the Modernist surface. Except that the Brillo Boxes represent, through their label, an outside world. When these empty containers were piled high at the Stable Gallery in 1964, they formed an architecture of empty containers, as depicted in Fred McDarrah’s iconic photographs of Warhol among his Brillo Boxes. In these photographs, the beholder enters an apparent warehouse of container culture, reconfigured as an image of its packaging-and-labeling-and-signifying system, but absent the goods. The French theorist Jean-Francois Baudrillard made much of the emptiness of these boxes with their signifying labels, writing that “the simulacrum is never that which conceals truth – it is the truth which conceals that there is none. The simulacrum is true.”35 Because the simulacrum is hollow, in other words, the container is empty. In and of themselves, in other words, these signs (whether Brillo box, Campbell’s Soup, or Movie Star) have no meaning, which emptiness demonstrates the socially alienating nature of commodity capitalism and its empty, but signifying, containers in particular. Not surprisingly, Pop appears in “Art and Objecthood” as “an episode in the history of taste,” which fleeting nature associates it with throw-away culture, with the commodity, the spectacle, and its boxes.36 From this perspective, the idea that there is any criticality at all in Pop Art (whether by scuff mark, punctum, or compulsive repetition of vacuity) becomes absurd. Which it is, or at least has always seemed so to me.

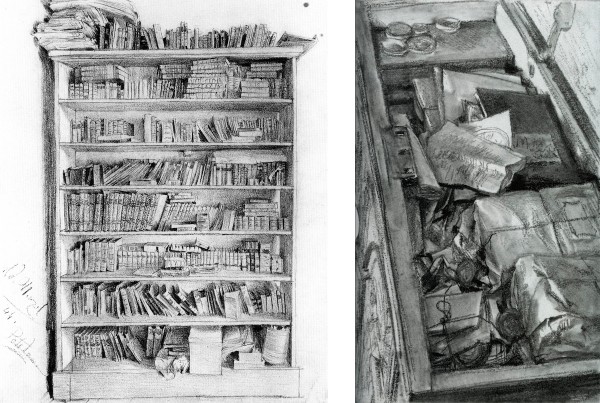

What are we to make, then, of Fluxus click-boxes, briefcases, cardboard containers and book objects, which are all handheld, or tabletop box objects that are opened and then used by the beholder? Significantly, the objects contained in many of the kits were purchased from the seconds bins on Canal Street. Which fact locates them very specifically in the object-hood of SoHo. In these kits, both vision and touch, or to borrow from Fried, eyesight and body, work together to make contact with more than the object’s surface. When used as intended (which they rarely are) little things inside the boxes are taken out. Click. Usually one by one, Click. Click. Then the tiny ball or pin or button or cap is handled and sniffed, or touched or prodded or used or listened to or tasted. Click. Then the small objects are returned to the box, which is then closed. Click. The bracketed experience, which is necessary for its standing as art (and which comes from the origins of Fluxus in music), is circumscribed by the physical space and time between the beholder’s encounters with inside of the box, the outside of the box and the movement of the body (hands, arms, face) interacting with its contents. The exploratory intent behind these actions embodies the mechanics of their status as objects of aesthetic interest (Fried’s term).

Clearly, the Fluxkit rejects the vision-based, Renaissance-type humanism that generated the perspective boxes that were closed up by Modernist painters and sculptors in rendering self-relational, away-from-the-world-turning artworks that gave Modernism its grace-full presentness. However, they also rejected the idealized box forms, the gestalt container aspect, of gallery-friendly Minimalism. The kits nevertheless produce remarkably absorptive, aesthetic experiences that both tune the person to the world and engender a way of being in the world that allows for critical distance from the normative sensory paradigm, as Modernism would have us do. This fulcrum of experience and critical distance results in the educative, positive, connective, effect theorized by Dewey. George Maciunas’s paradigmatic 1964 Fluxus cc fiVe ThReE Fluxkit, for example, surveys many Fluxus artists’ boxed works inside a unifying container. It has variable contents depending on when a given version was actually fabricated. Each retrofitted briefcase contains: a noisemaker by Joe Jones, an Endless Box by Mieko (Shieko) Shiomi that is made of nested paper boxes, a Finger Box by Ay-O that offers the beholder a tactile surprise inside a blind finger hole, a Bean Rolls by Alison Knowles that consist of an extended study of the legume printed on strips of paper and with a few beans in a mass manufactured cigar box, and a dozen or so other works, including performance event instructions on cards in latched click-cases. At least until they enter the museum, these boxed items remain accessible for sensory examination: things can be pulled out and put back into the box. These are sensory games calibrated to an ever expanding sensorium. According to art historian Benjamin Buchloh, Fluxkits “foreground the accumulation of objects over the mere mapping of the painterly surface by the grid structure of the found crate.”37 Thus, this work displays what Buchloh has described as “performative enactment, one where object and subject would suddenly appear as equal actors”38 in terms that resist the problems of theatricality that would inhere, were they merely made up of a “mere mapping of the painterly surface by the grid structure of the found crate,” which I would argue is rightly identified as a risk in Minimalism as described by Fried. The Fluxkit, in other words, is no passive receptacle or staging devise. Rather, the artwork happens in the interaction of the user with the boxes’ insides and outsides, content and context, seeing and embodiment. Because they contain things engaged with in performative enactment, in summary, the container of the Fluxkit is experientially full in Fried’s terms.

The beholder uses the work, which becomes something like a Heideggerian tool through which whatever object is at hand is understood more deeply through the elicited curiosity; “Curiosity . . . does not seek the leisure of tarrying observantly, but rather seeks restlessness and the excitement of continual novelty and changing encounters.”39 However, unlike a proper tool (a hammer, pliers), the Fluxus work lacks instructions. There isn’t really a single right way (though there are many wrong ways) to use it. The beholder/user of Fluxkits almost by definition uses the things in them in surprising ways – to tell stories, to make a visual joke with a friend who may be standing nearby, to establish a limit to some part of their sensory exploration. Can I hear this cotton ball in my ear? Does this prong make me sneeze if I put it in my nose? If I plunge my finger in this hole here, will it come out bloody? Ah, cotton. Ouch, nails! We had many a Fluxkit lying around when I was young and the things in them were not especially unlike the artifacts and objects elsewhere in my world, except they were framed and so we interacted with them intentionally. I recall fondly Bracken Hendricks, (another Fluxkid and the son of Fluxus artist, Geoff Hendricks) meticulously collecting feces samples in boxes and labeling them carefully before sending them to George Maciunas for his notorious collection.

Fluxus containers, in summary, initiate the beholder (a holding, handling beholder, maybe a tool-being holder in the Heideggerian sense) to explore and take interest in the world. The boxes sensitize the user to a world where the public is overwhelmed and numbed by the excess goods proliferating, literally ad nauseum, in the world and landing in the seconds bins along Canal Street, where Maciunas made use of them as artworks. The kits express a collective obligation (or opportunity) to repurpose the excess manufactured articles of late capitalism. The kits make this argument as artworks that track a fundamental shift in the sensorium of the time away from narrowly conceived vision-as-everything, a logic that lies very much at the core of Greenbergian flatness, but not Friedian shape, if we see shape in terms of embodied knowledge and experiential fullness. Today, we might call it recycling, precycling or object hacking. In sum, while Fluxkits use containers to organize a wealth of sensory information, they are not hollow in Fried’s sense. Therefore, while the boxes may be shapeless, the aesthetic experience the work generates through sensory exploration, does so around a range of carefully framed, sensory-cum-cognitive structures uniquely knowable in SoHo in the 1960s, which could be described as the neighborhood of objecthood.

Instead of Renaissance Humanism putting Man at the center of the world (by which logic natural resources and non-white peoples could be readily exploited), Modern work proposed a material and symbolic independence from that world. The political relevance of Modernism, for its proponents, lay in the simultaneously formal and social progress of this turning-away. Art becomes a bracket from the noise and distraction. Greenberg described kitsch, whether of the tin-pan alley, commodity, or passive realist artistic variety, in these terms. Fundamentally, most Fluxus artists likewise rejected mass-generated popular art forms (as manipulations of the public), passive consumerism (of the Pop Art variety) and the narrowly visual definition of fine art (rejected by Modernists on account of the formal/material basis of each medium). In other words, at least with regard to Fluxus, there are some compelling overlaps with Fried’s position.

Fried and many artists in Fluxus both responded to container culture in the negative, even as Fluxus used the container to propose an alternative to mainstream container culture of both the commodity and artworld kind. Fried rejected the hallowed hollowness of the box that folded out into everything, whereas Fluxus artists (with some exception) filled the boxes with the overstocks of consumer culture. Both rejected corporate kitsch, while Fluxus artists often embraced vaudevillian and industrial low culture as an alternative to both Modernist purity and mainstream culture. Also, it should be said, both rejected theatricality (or used the term theater in the pejorative), but aimed the term at different aspects of culture, but on similar grounds. Finally, while many Fluxus artists have used boxes and containers to hold their works, it is important to understand that the aesthetic model they are working with is multisensory, and often specifically musical. Beyond the party politics of some Fluxus artists (George Maciunas, Henry Flynt for example), the thrust of Fluxus work lies often in its association with music (and the idea of the direct encounter), or more specifically with the knowledge gained through an intermedial understanding of music as a medium, which includes the written aspect of notation, the visual/graphic aspect of how it is read, the space of performance, the sensory qualities of each instrument, and the body of the performer. Intermedia, by this reading, is not the same thing as theater in the Friedian sense, since it refers to artists identifying the places where the unique aspects of established media interact across sensory boundaries.

Performativity and theatricality overlap, in other words, in the predictability, passive acceptance, spectacular scale, and affirmative values of some of each of these movements – or at least in the amped up commercial version of Minimalism, Pop Art, and (even some) Fluxus. The academic version of the postmodern [the institutionalized variant associated with today’s hyper commercialized art market] has perverted the aesthetic, social and material effects of its founding community of artists. Fried, one could argue, saw the betrayal coming, by virtue of his emphasis on a few key terms that tell us a lot about how containers work: The inside/outside relationality of the container, the everyday materials of container culture, the confusion of sign and symbol, and a particular vulnerability to theatricality. What began for these artists and their audiences as an inquisitive, intimate, funky encounter with an emerging sense of the real (the container, its things, the loft space) in and as art, was attacked in Fried’s account where he seemed (almost uncannily) to anticipate the change in kind that came with the commercialization of these art movements. Clearly the insight lay in his predisposition, as a proponent of Modernism, to reject the work. The inside/outside nature of the container became a scalable stage-set, the everyday materials of container culture became a phantasmagoria of consumerism, the examination of sign and symbol yielded to spectacle, and theatricality (intermedia) was transformed from an examination of the overlapping spheres of media practice into an utter absence of media signposts and a proliferation of the technological sublime.

Notes

“Art and Objecthood” is part of an ongoing argument about the nature of Modernism and what follows it, an argument conducted both with Clement Greenberg and with (I guess we can now say) Post- modernist figures such as Donald Judd and Tony Smith. It is thus both an account of a particular historical episode in the visual arts, at a particular time and place, and the development of a (suitably historicized) ontology of the work of art, in the course of which the concept of something called “theatricality” is deployed to illuminate not only the situation of beholder and artwork, but also such questions as that of the nature of an artistic medium, and the conditions of expressiveness in art. The central figure in the argument about Modernism is Clement Greenberg, but the dialectic he describes is part of the conceptual repertoire of many diverse writers. At one point Fried paraphrases Greenberg’s story in the following way. “Starting around the middle of the nineteenth century, [Greenberg] claimed in ‘Modernist Painting,’ the major arts, threatened for the first time with being assimilated to mere entertainment […] discovered that they could save themselves from that fate ‘only by demonstrating that the kind of experience they provided was valuable in its own right and not to be obtained from any other kind of activity.’”

The following continuation of this passage from Greenberg is also quoted by Fried:

Each art, it turned out, had to effect this demonstration on its own account. What had to be exhibited and made explicit was that which was unique and irreducible not only in art in general but also in each particular art. Each art had to determine, through the operations peculiar to itself, the effects peculiar and exclusive to itself. […]

It quickly emerged that the unique and proper area of competence of each art coincided with all that was unique to the nature of its medium. The task of self-criticism became to eliminate from the effects of each art any and every effect that might conceivably be borrowed from or by the medium of every other art. Thereby each art would be rendered “pure,” and in its “purity” find the guarantee of its standards of quality as well as of its independence. “Purity” meant self-definition, and the enterprise of self-criticism in the arts became one of self-definition with a vengeance.[3]

This describes one way of relating the process of Modernism, in the visual arts anyway, to a developmental story, and a Kantian-style quest for autonomy through self-definition, and with an equally Kantian invocation of an idea of “purity,” this time focusing on the nature or irreducible essence of a particular artistic medium. The story Fried tells also describes Modernism as in part a crisis and working-through of self-definition which focuses on the question of an artistic medium, but the distance between the two accounts is considerable, particularly with respect to the idea of “irreducible essences” and the rhetoric of purity and reduction. And in fact Fried’s critique of the ideology of Minimalism, which positioned itself as the total rejection of both Greenbergian aesthetics and the painting and sculpture he championed, is based on what Fried sees as shared by both camps in their interpretation of the process of Modernism, in their dependence on ideas of reduction and essence in connection with an artistic medium. As he puts it in the Introduction to his recent collection of his earlier art criticism, “a major strand of my argument in […] ‘Art and Objecthood’ is that literalism arose within modernism as a misreading of its dialectic (a misreading anticipated, on the plane of theory, by Greenberg in ‘Modernist Painting’ […]” (45).

In the essay “Art and Objecthood” itself, this diagnosis is made out in relation to both the concepts of theatricality and of objecthood. In the visual arts, the physicality of a particular medium becomes a matter of a different kind of self-consciousness, a different necessity of self-consciousness, at least since Manet. In Greenberg’s terms, the dialectic of Modernism is a process of refining the self-definition of an artform to the unique and irreducible facts of the physical basis of its medium, in particular the delimited flatness of the picture-support, in the case of painting. Literalist (or Minimalist) practice responds to this reading of the situation by the insistent projection of the essential “object-character” of the work of art, something neither quite painting nor quite sculpture. In “Art and Objecthood,” Fried puts it this way: prior to the present situation (1967),

the risk, even the possibility, of seeing works of art as nothing more than objects did not exist. That such a possibility began to present itself around 1960 was largely the result of developments within modernist painting. Roughly, the more nearly assimilable to objects certain advanced painting had come to seem, the more the entire history of painting since Manet could be understood—delusively, I believe—as consisting in the progressive (though ultimately inadequate) revelation of its essential objecthood, and the more urgent became the need for modernist painting to make explicit its conventional—specifically, its pictorial—essence by defeating or suspending its own objecthood through the medium of shape. Literalist sensibility is, therefore, a response to the same developments that have largely compelled modernist painting to undo its objecthood—more precisely, the same developments seen differently, that is, in theatrical terms, by a sensibility already theatrical, already (to say the worst) corrupted or perverted by theater. (160-161)

The conceptual interplay between the ideas of theater and of objecthood, in their relation to the pressures of Modernism, had been prepared for one paragraph back, which declares that “the imperative that modernist painting defeat or suspend its objecthood is at bottom the imperative that it defeat or suspend theater,” and indeed, refers in passing to the “theatricality of objecthood” itself (160).

So, what is theatricality in this context, such that it can bear such an intimate relation to the idea of objecthood? And what do the pair of them mean to tell us about the concept of a work of art, such that in a given time and place they can count as something like the negation of art, even self-consciously so? I’m thinking here of the punctuating sentence early in the essay that says: “The literalist espousal of objecthood amounts to nothing other than a plea for a new genre of theater, and theater is now the negation of art” (153). To invoke the idea of the negation of art is a very defining form of criticism, however historically localized in application, and even when, as Fried has pointed out, its basic terms of criticism are shared by both critic and the practitioners of the situation he is diagnosing. It is a characteristically Modernist form of absolute criticism of art, disarming more local terms of criticism and appreciation in favor of raising the question of the status of some object as painting at all, as art or as a negation of art. That is, something like the very concept and possibility of art is addressed not only in Fried’s essay but in the discourse and I think we can say in the installations of the Minimalist artists under discussion. Objecthood and theatricality are linked not only with respect to something like the negation of art, but the negation in question is something pursued from within the world of the arts itself, something pursued in the very name of the negation of art. This is not an unheard of situation in culture or discourse, but it is also one that is only possible in certain times and places. We’re familiar with the presence of hostility to the very idea of art, which is somehow yet also something internal to the nature and practice of art itself, something which, since the twentieth century at least, lives side by side with some of the highest achievements of the individual arts. But that doesn’t mean we understand it very well, or how it is so much as possible for movements defining themselves against “art” could emerge and flourish within the cultures of what we still call artistic practice. The idea that it is an internal, defining, possibility of art, at least in its Modernist practice, that it may go astray from itself, or lose itself, or seek to “go beyond itself’ or bring itself to an end, is something that Melville’s work has provided new terms for thinking about, and I hope to say something about this possibility later.[4] Its truth as a phenomenological description of one’s engagement with much twentieth-century art doesn’t efface the paradoxical character of speaking of the very practice of an art going astray from itself. And indeed something like an Institutional theory of art seems designed to prevent such descriptions in terms of crisis or scandal, since nothing independent of the structures of ratification (nothing in artistic history or practice) is invoked to give content to the idea of something being strayed from. We avoid paradox this way, perhaps, but then the social, cultural and political phenomenon we were trying to describe also disappears from view. If either such straying or such negation is indeed an internal possibility for modernist art, and not a matter of external threat (from political repression, from public indifference or contempt), then that fact will be a deep characterization of it, something that defines it and distinguishes it from other discourses and cultural practices.

But the more specific questions I want to raise have to do with the relation of the terms “theater” and “objecthood” as they figure in Fried’s reading of the “dialectic of modernism.” First and most crudely of all, the ideas of “theatricality” and of “objecthood,” even in the context Fried prepares for them, just sound like quite different, even opposed, ideas; so there’s a question of how they can be deployed in support of each other as terms of criticism, describing an internal threat to art as such in a modern context. “Theater” is the name for something that is a possibility for the domain of expression, a form of staging or self-projection, whereas “objecthood” would appear to name the realm of things outside that domain altogether. In “Art and Objecthood,” part of the criticism of the theatrical work is given in specifically anthropomorphic terms, in the “complicity that the work extorts from the beholder” (155), in its tendency to “confront the beholder” (154), in effects of presence which reflect a kind of “demand that the beholder take it into account” (155). How, then, is theatricality understood in these terms of personification to be seen as part of “the risk, even the possibility, of seeing works of art as nothing more than objects”?

An object qua object, a brick or a stretch of highway, is neither expressive nor withholding of expression; and if such an object is seen as silent, its silence is not that of a person holding his tongue. Fried, however, characterizes the installations of Minimalism in terms of the “projection” of objecthood, which is a different matter entirely, since projection, exhibition and display immediately involve us in the domain of expression. The “mere” or “pure” objecthood of a brick is thus not a possibility any longer. In the installation space everything takes place, as it were, under the sign of expression, even if it is one that is thwarted, denied, or suspended. The specter of anthropomorphism haunts Literalist practice like a bad conscience. In trying to tease out the relation between objecthood and theatricality, I want right now just to insist that it is not objecthood itself, but rather the projection of objecthood, that is crucial to this relation. This will necessarily be a project at odds with itself, since the projecting, displaying hand has to keep itself fully out of view, has to retreat to tautology when any gestural point comes to consciousness. (Judd: “To me the piece with the brass and the five verticals is above all that shape.”[5]) So long as we are in a situation of projection and exhibition, objecthood can’t be the plain fact of the matter, but can only be something exploited, something deployed and retreated to, a refuge from specific demands of significance. Hence one aspect of relating the concepts of theatricality and (the projection of) objecthood in this context will be found in the idea of an activity which disallows transparency about itself.

A related question concerns the connection between the idea of theatricality and the production of effects. If objecthood itself belongs outside the domain of the expressive, it is very much within the realm of cause and effect. And the installations of Minimalist practice are self-consciously understood in terms of the controlled production of effects. In Robert Morris’s words, distinguishing his installations from earlier artistic practice, “But the concerns now are for more control of and/or cooperation of the entire situation. Control is necessary if the variables of object, light, space, body are to function.”[6] This is one of the places I had in mind earlier when I said that the terms of criticism of Fried’s diagnosis are in many instances shared by the Minimalist practitioners themselves. The emphasis on the controlled production of effects is both part of his case against theatricality and another dimension of its relation to objecthood. The installations created a kind of “mise en scène” that was “extraordinarily charged,” and “It was as though their installations infallibly offered their audience a kind of heightened perceptual experience, and I wanted to understand the nature of that surefire, and therefore to my mind essentially inartistic, effect.”[7] It’s the relation of the surefire and the inartistic I want to just point to now. Kant argues that it defines a judgment of the beautiful as such that it cannot be the conclusion of a demonstration, or as it is sometimes put, that there can be no principles of taste, general rules which could require such a verdict as it were ahead of time, prior to experience of the object. A parallel argument in Kant claims that there can be no laws of taste, that is, descriptive premises which could then support an empirical law to the effect that some object will in fact be found beautiful. For Kant, this absence of laws defines the judgment of the beautiful just as the possibility of ordinary empirical judgment. I don’t know if Fried means to be alluding to this in divorcing the aesthetic from the realm of sure-fire production of effects, but I bring it up here to anticipate a further way the ideas of theatricality and of objecthood, for all their surface opposition, can be seen as parallel repudiations of the conditions of expressiveness in art. I need to go into one final characterization of theatricality in Fried to prepare for this, but the thought I would like to arrive at is that artistic or gestural expression involves the interplay between an assumption of authority for what one means, together with a yielding of control over the final effects produced, the desired uptake. In this light, Literalist practice, as depicted in “Art and Objecthood,” declares its anti-artistic status and the repudiation of expressiveness in the ambition of total control of the situation of beholding, coupled with the refusal of all authority for how it is to count for us.

I’ve asked some questions about the idea of theatricality in connection with objecthood, the negation of art, and the emphasis on the controlled production of effects. The last characterization of theatricality which I want to bring in here in some ways brings in an apparently even more heterogeneous set of concerns than the others, but also brings us back to the Greenbergian dialectic of Modernism and the reflective concern with the conditions of an artistic medium as such.[8]

One of the concluding moments of “Art and Objecthood” comes at the idea of theater in the following way. “The concepts of quality and value—and to the extent that these are central to art, the concept of art itself—are meaningful, or wholly meaningful, only within the individual arts. What lies between the arts is theater” (164). Let me try to say something about the issue of “medium-specificity” in Fried’s criticism, before I worry explicitly about how the challenging or evading of such specificity could be called by the same name as the concept we’ve been tracking alongside that of “objecthood.” We’ve briefly seen the appeal to an ideal of self-criticism and artistic self-definition in Greenberg’s story of the Modernist pressures brought to bear on the relation of the artist to his artistic medium. At the same time, Greenberg appears to see the response to these pressures primarily in terms of asserting the particular value of an artform with the purity and exclusivity of its medium, hence the internal quest for the “unique and irreducible” features of its medium. This is not the place to unravel the different strands of uniqueness, intrinsic value, and the idea of the irreducible essence of a medium, but Fried’s essay[9] already helps to show how the idea of self-definition in the specification of an artistic medium can be disentangled from both Greenberg’s teleological story and the idea of “essence” that he works with. On Fried’s account, as I understand it, what defines a particular artistic medium is nothing more or less than the evolving histories of artistic and critical practice themselves, and is no more timeless or predictable than they are. This shows another way in which the spatial picture of purity (i.e., what is genuinely “internal” to an artform versus what is merely “external” to it) does more harm than good. What matters is not a medium’s conformity to some previously defined “essence,” but the assumption of responsibility for self-definition. Self-definition which, of course, doesn’t insure artistic success, but provides (some of) the criteria for what is to count as success or failure. It is the refusal of this moment of self-definition, at least in the writings of the Literalist artists Fried takes on, which distinguishes their relation to the idea of a medium of art from a Modernist one.[10]

There is of course a much more detailed story, but even if this correction of Greenberg is accepted, and this placement of the issues of self-definition and medium-specificity is found importantly right, the question I want to raise is how can this vision be brought into alignment with the family of concepts we traced around that of “theatricality” such as to motivate the claim that it is theater, of all things, which lies between the individual arts?

For some help here, I want to turn again to Melville’s “Notes on Allegory” essay. At one point in “Art and Objecthood,” Fried says the following: “… what is wrong with literalist work is not that it is anthropomorphic but that the meaning and, equally, the hiddenness of its anthropomorphism are incurably theatrical” (157). After quoting this passage, Melville offers the following gloss:

What Fried objects to in the work of Tony Smith is the way in which it offers itself to its beholder as (not simply a person but) a person who then refuses to allow one a human relation to itself—it is work that distances itself from (the subject it thereby forces to become merely) its beholder. It refuses to let itself mean—be taken as meaning; it is soulless, it enforces the condition Cavell calls “soul-blindness” on its viewer. We have known people with this kind of irony—who would make us the decider of their ensouledness, who would make us decide for them the humanity of their expressions. (“Notes,” 153)

What strikes me first of all in this passage is the interplay depicted between activity and passivity, specifically activity and passivity as they are implicated together in the very idea of expression. Something is being objected to in this passage, something in connection with the place of expression in Literalist theory and practice. At first the Literalist work is said to refuse to “let itself” mean, or be taken as meaning. Without yet asking just how to understand such a refusal, we can hear in these words a refusal of a kind of passivity or exposure, a refusal to be taken or even “read” by another person as meaning this rather than that. We might then understand such a refusal as a refusal to relinquish a kind of control over one’s field of expression. But the next sentence, which presents itself as a kind of gloss on this one, refers us to a familiar kind of person “who would make us the decider of their ensouledness, who would make us decide for them the humanity of their expressions.” And that sounds like a (fundamental) kind of relinquishment itself, rather than a refusal of such yielding. If this is the same person who is refusing to let himself be read, it is not through an assertion of a kind of dictatorial authority over the true meaning of his expressions (that might be one sort of “refusal”), but rather through an abandonment of any such authority. There is surely something deeply right in this doubleness, this interplay between a kind of passivity and a kind of authority, and that this tells us something important about the conditions of expression in art and elsewhere, and about what “theatricality” could mean in this context, in relation to the issues of medium-specificity and the idea of “theater” in Fried’s sense as that which lies between the arts. And how “theater” could, in a particular historical context, come to seem or be the enemy of art itself.

The story of Modernism that brings literalism and objecthood to bear on the concept of a medium of art begins from a sense, surely undeniable, that insofar as there is a concept of “the modern” in art, it is defined by the fact of crisis in the artist’s relation to the history and conventions of the medium. One of Stanley Cavell’s formulations for this situation is the following from The World Viewed:

Modernism signifies not that the powers of the arts are exhausted, but on the contrary that it has become the immediate task of the artist to achieve in his art the muse of the art itself […] One might say that the task is no longer to produce another instance of an art but a new medium within it. […] It follows that in such a predicament media are not given a priori. The failure to establish a medium is a new depth, an absoluteness, of artistic failure.[11]

The imperative to establish an artistic medium means that the artist herself must somehow assume the authority to determine and declare how her work is to count for us, determine as just what medium of art it is to confront its specific possibilities of success and failure. In art, as well as in ordinary speech and gesture, possibilities of meaning and expression exist only insofar as there are answers to the criterial questions of what sort of thing is the subject of expression here, what speech, what action, what medium of expression. Since this is a matter of establishing and declaring criteria, someone (plural or singular) has to speak with a particular authority here, and have that authority recognized, accepted. This is the moment of self-definition Greenberg saw as defining the task of modernism, but without his assimilation of the tasks of autonomy and self-definition to the aims of purity and exclusivity. Medium-specificity becomes an issue precisely because “media are not given a priori,” and not guaranteed by tradition or placement in history either.

The person “who would have us decide for them the humanity of their expressions” is refusing the authority to declare what he or she is up to and why or how it should count for us. And yet, as we are imagining this scenario, something has just been said, something has been presented or projected, or we are confronted by something in a gallery space. Mere literality, literal literality, is not an option here, and in any case we are confronted here by an inchoate demand for response.[12]

The determination of a medium defines what is to count as artistic success or failure, and hence sets the terms of artistic risk, and thus involves a relinquishing of control (over the response of its audience) for the same reason that it demands an assumption of authority (in making the criterial declaration of a medium itself). The possibilities of expressiveness, whether in art or elsewhere, involve requirements of both types: the assumption of authority to, as it were, speak criterially, and the relinquishing of control over the ultimate destination, or the further reaches of the response being sought out or tested. The Literalist objects and installations can be seen as turning these conditions inside out, for they present themselves as simultaneously refusing all authority to determine a particular medium or mode of expressivness, declaring how this is to count for us, while also insisting on a kind of total control of the situation of the beholder. As if artistic success or failure could be produced through sheer force of control; as if control could do the work of authority. (And from this perspective there is nothing for the beholder to choose between the twin post-modernist strategies of Total Control and Total Chance.)

In this way we can see how something called theatricality could be both part of the pressure of objecthood emerging out of the Greenbergian reading of Modernism’s dialectic of self-definition, and how, as part of this same story, it can be said that “what lies between the arts is theater.” As hopelessly compressed as this is, I hope it also starts the way toward understanding how, in a given time and place, theater in this sense could come to seem the very negation of art, that is, something striking at its very concept, and not simply one of the countless failings (of nerve, of taste, of clarity) that are constitutive risks of any practice of art.

I’ll end with two last remarks. The first is that most of this paper has been a continuous attempt to lead up to the question: “Why isn’t Literalism part of the same motor of self-criticism that Greenberg and others take to be definitive of Modernism?” The answer to that is not entirely in place, of course, but I hope to have ended up posing the question.