“Art and Objecthood” is part of an ongoing argument about the nature of Modernism and what follows it, an argument conducted both with Clement Greenberg and with (I guess we can now say) Post- modernist figures such as Donald Judd and Tony Smith. It is thus both an account of a particular historical episode in the visual arts, at a particular time and place, and the development of a (suitably historicized) ontology of the work of art, in the course of which the concept of something called “theatricality” is deployed to illuminate not only the situation of beholder and artwork, but also such questions as that of the nature of an artistic medium, and the conditions of expressiveness in art. The central figure in the argument about Modernism is Clement Greenberg, but the dialectic he describes is part of the conceptual repertoire of many diverse writers. At one point Fried paraphrases Greenberg’s story in the following way. “Starting around the middle of the nineteenth century, [Greenberg] claimed in ‘Modernist Painting,’ the major arts, threatened for the first time with being assimilated to mere entertainment […] discovered that they could save themselves from that fate ‘only by demonstrating that the kind of experience they provided was valuable in its own right and not to be obtained from any other kind of activity.’”

The following continuation of this passage from Greenberg is also quoted by Fried:

Each art, it turned out, had to effect this demonstration on its own account. What had to be exhibited and made explicit was that which was unique and irreducible not only in art in general but also in each particular art. Each art had to determine, through the operations peculiar to itself, the effects peculiar and exclusive to itself. […]

It quickly emerged that the unique and proper area of competence of each art coincided with all that was unique to the nature of its medium. The task of self-criticism became to eliminate from the effects of each art any and every effect that might conceivably be borrowed from or by the medium of every other art. Thereby each art would be rendered “pure,” and in its “purity” find the guarantee of its standards of quality as well as of its independence. “Purity” meant self-definition, and the enterprise of self-criticism in the arts became one of self-definition with a vengeance.[3]

This describes one way of relating the process of Modernism, in the visual arts anyway, to a developmental story, and a Kantian-style quest for autonomy through self-definition, and with an equally Kantian invocation of an idea of “purity,” this time focusing on the nature or irreducible essence of a particular artistic medium. The story Fried tells also describes Modernism as in part a crisis and working-through of self-definition which focuses on the question of an artistic medium, but the distance between the two accounts is considerable, particularly with respect to the idea of “irreducible essences” and the rhetoric of purity and reduction. And in fact Fried’s critique of the ideology of Minimalism, which positioned itself as the total rejection of both Greenbergian aesthetics and the painting and sculpture he championed, is based on what Fried sees as shared by both camps in their interpretation of the process of Modernism, in their dependence on ideas of reduction and essence in connection with an artistic medium. As he puts it in the Introduction to his recent collection of his earlier art criticism, “a major strand of my argument in […] ‘Art and Objecthood’ is that literalism arose within modernism as a misreading of its dialectic (a misreading anticipated, on the plane of theory, by Greenberg in ‘Modernist Painting’ […]” (45).

In the essay “Art and Objecthood” itself, this diagnosis is made out in relation to both the concepts of theatricality and of objecthood. In the visual arts, the physicality of a particular medium becomes a matter of a different kind of self-consciousness, a different necessity of self-consciousness, at least since Manet. In Greenberg’s terms, the dialectic of Modernism is a process of refining the self-definition of an artform to the unique and irreducible facts of the physical basis of its medium, in particular the delimited flatness of the picture-support, in the case of painting. Literalist (or Minimalist) practice responds to this reading of the situation by the insistent projection of the essential “object-character” of the work of art, something neither quite painting nor quite sculpture. In “Art and Objecthood,” Fried puts it this way: prior to the present situation (1967),

the risk, even the possibility, of seeing works of art as nothing more than objects did not exist. That such a possibility began to present itself around 1960 was largely the result of developments within modernist painting. Roughly, the more nearly assimilable to objects certain advanced painting had come to seem, the more the entire history of painting since Manet could be understood—delusively, I believe—as consisting in the progressive (though ultimately inadequate) revelation of its essential objecthood, and the more urgent became the need for modernist painting to make explicit its conventional—specifically, its pictorial—essence by defeating or suspending its own objecthood through the medium of shape. Literalist sensibility is, therefore, a response to the same developments that have largely compelled modernist painting to undo its objecthood—more precisely, the same developments seen differently, that is, in theatrical terms, by a sensibility already theatrical, already (to say the worst) corrupted or perverted by theater. (160-161)

The conceptual interplay between the ideas of theater and of objecthood, in their relation to the pressures of Modernism, had been prepared for one paragraph back, which declares that “the imperative that modernist painting defeat or suspend its objecthood is at bottom the imperative that it defeat or suspend theater,” and indeed, refers in passing to the “theatricality of objecthood” itself (160).

So, what is theatricality in this context, such that it can bear such an intimate relation to the idea of objecthood? And what do the pair of them mean to tell us about the concept of a work of art, such that in a given time and place they can count as something like the negation of art, even self-consciously so? I’m thinking here of the punctuating sentence early in the essay that says: “The literalist espousal of objecthood amounts to nothing other than a plea for a new genre of theater, and theater is now the negation of art” (153). To invoke the idea of the negation of art is a very defining form of criticism, however historically localized in application, and even when, as Fried has pointed out, its basic terms of criticism are shared by both critic and the practitioners of the situation he is diagnosing. It is a characteristically Modernist form of absolute criticism of art, disarming more local terms of criticism and appreciation in favor of raising the question of the status of some object as painting at all, as art or as a negation of art. That is, something like the very concept and possibility of art is addressed not only in Fried’s essay but in the discourse and I think we can say in the installations of the Minimalist artists under discussion. Objecthood and theatricality are linked not only with respect to something like the negation of art, but the negation in question is something pursued from within the world of the arts itself, something pursued in the very name of the negation of art. This is not an unheard of situation in culture or discourse, but it is also one that is only possible in certain times and places. We’re familiar with the presence of hostility to the very idea of art, which is somehow yet also something internal to the nature and practice of art itself, something which, since the twentieth century at least, lives side by side with some of the highest achievements of the individual arts. But that doesn’t mean we understand it very well, or how it is so much as possible for movements defining themselves against “art” could emerge and flourish within the cultures of what we still call artistic practice. The idea that it is an internal, defining, possibility of art, at least in its Modernist practice, that it may go astray from itself, or lose itself, or seek to “go beyond itself’ or bring itself to an end, is something that Melville’s work has provided new terms for thinking about, and I hope to say something about this possibility later.[4] Its truth as a phenomenological description of one’s engagement with much twentieth-century art doesn’t efface the paradoxical character of speaking of the very practice of an art going astray from itself. And indeed something like an Institutional theory of art seems designed to prevent such descriptions in terms of crisis or scandal, since nothing independent of the structures of ratification (nothing in artistic history or practice) is invoked to give content to the idea of something being strayed from. We avoid paradox this way, perhaps, but then the social, cultural and political phenomenon we were trying to describe also disappears from view. If either such straying or such negation is indeed an internal possibility for modernist art, and not a matter of external threat (from political repression, from public indifference or contempt), then that fact will be a deep characterization of it, something that defines it and distinguishes it from other discourses and cultural practices.

But the more specific questions I want to raise have to do with the relation of the terms “theater” and “objecthood” as they figure in Fried’s reading of the “dialectic of modernism.” First and most crudely of all, the ideas of “theatricality” and of “objecthood,” even in the context Fried prepares for them, just sound like quite different, even opposed, ideas; so there’s a question of how they can be deployed in support of each other as terms of criticism, describing an internal threat to art as such in a modern context. “Theater” is the name for something that is a possibility for the domain of expression, a form of staging or self-projection, whereas “objecthood” would appear to name the realm of things outside that domain altogether. In “Art and Objecthood,” part of the criticism of the theatrical work is given in specifically anthropomorphic terms, in the “complicity that the work extorts from the beholder” (155), in its tendency to “confront the beholder” (154), in effects of presence which reflect a kind of “demand that the beholder take it into account” (155). How, then, is theatricality understood in these terms of personification to be seen as part of “the risk, even the possibility, of seeing works of art as nothing more than objects”?

An object qua object, a brick or a stretch of highway, is neither expressive nor withholding of expression; and if such an object is seen as silent, its silence is not that of a person holding his tongue. Fried, however, characterizes the installations of Minimalism in terms of the “projection” of objecthood, which is a different matter entirely, since projection, exhibition and display immediately involve us in the domain of expression. The “mere” or “pure” objecthood of a brick is thus not a possibility any longer. In the installation space everything takes place, as it were, under the sign of expression, even if it is one that is thwarted, denied, or suspended. The specter of anthropomorphism haunts Literalist practice like a bad conscience. In trying to tease out the relation between objecthood and theatricality, I want right now just to insist that it is not objecthood itself, but rather the projection of objecthood, that is crucial to this relation. This will necessarily be a project at odds with itself, since the projecting, displaying hand has to keep itself fully out of view, has to retreat to tautology when any gestural point comes to consciousness. (Judd: “To me the piece with the brass and the five verticals is above all that shape.”[5]) So long as we are in a situation of projection and exhibition, objecthood can’t be the plain fact of the matter, but can only be something exploited, something deployed and retreated to, a refuge from specific demands of significance. Hence one aspect of relating the concepts of theatricality and (the projection of) objecthood in this context will be found in the idea of an activity which disallows transparency about itself.

A related question concerns the connection between the idea of theatricality and the production of effects. If objecthood itself belongs outside the domain of the expressive, it is very much within the realm of cause and effect. And the installations of Minimalist practice are self-consciously understood in terms of the controlled production of effects. In Robert Morris’s words, distinguishing his installations from earlier artistic practice, “But the concerns now are for more control of and/or cooperation of the entire situation. Control is necessary if the variables of object, light, space, body are to function.”[6] This is one of the places I had in mind earlier when I said that the terms of criticism of Fried’s diagnosis are in many instances shared by the Minimalist practitioners themselves. The emphasis on the controlled production of effects is both part of his case against theatricality and another dimension of its relation to objecthood. The installations created a kind of “mise en scène” that was “extraordinarily charged,” and “It was as though their installations infallibly offered their audience a kind of heightened perceptual experience, and I wanted to understand the nature of that surefire, and therefore to my mind essentially inartistic, effect.”[7] It’s the relation of the surefire and the inartistic I want to just point to now. Kant argues that it defines a judgment of the beautiful as such that it cannot be the conclusion of a demonstration, or as it is sometimes put, that there can be no principles of taste, general rules which could require such a verdict as it were ahead of time, prior to experience of the object. A parallel argument in Kant claims that there can be no laws of taste, that is, descriptive premises which could then support an empirical law to the effect that some object will in fact be found beautiful. For Kant, this absence of laws defines the judgment of the beautiful just as the possibility of ordinary empirical judgment. I don’t know if Fried means to be alluding to this in divorcing the aesthetic from the realm of sure-fire production of effects, but I bring it up here to anticipate a further way the ideas of theatricality and of objecthood, for all their surface opposition, can be seen as parallel repudiations of the conditions of expressiveness in art. I need to go into one final characterization of theatricality in Fried to prepare for this, but the thought I would like to arrive at is that artistic or gestural expression involves the interplay between an assumption of authority for what one means, together with a yielding of control over the final effects produced, the desired uptake. In this light, Literalist practice, as depicted in “Art and Objecthood,” declares its anti-artistic status and the repudiation of expressiveness in the ambition of total control of the situation of beholding, coupled with the refusal of all authority for how it is to count for us.

I’ve asked some questions about the idea of theatricality in connection with objecthood, the negation of art, and the emphasis on the controlled production of effects. The last characterization of theatricality which I want to bring in here in some ways brings in an apparently even more heterogeneous set of concerns than the others, but also brings us back to the Greenbergian dialectic of Modernism and the reflective concern with the conditions of an artistic medium as such.[8]

One of the concluding moments of “Art and Objecthood” comes at the idea of theater in the following way. “The concepts of quality and value—and to the extent that these are central to art, the concept of art itself—are meaningful, or wholly meaningful, only within the individual arts. What lies between the arts is theater” (164). Let me try to say something about the issue of “medium-specificity” in Fried’s criticism, before I worry explicitly about how the challenging or evading of such specificity could be called by the same name as the concept we’ve been tracking alongside that of “objecthood.” We’ve briefly seen the appeal to an ideal of self-criticism and artistic self-definition in Greenberg’s story of the Modernist pressures brought to bear on the relation of the artist to his artistic medium. At the same time, Greenberg appears to see the response to these pressures primarily in terms of asserting the particular value of an artform with the purity and exclusivity of its medium, hence the internal quest for the “unique and irreducible” features of its medium. This is not the place to unravel the different strands of uniqueness, intrinsic value, and the idea of the irreducible essence of a medium, but Fried’s essay[9] already helps to show how the idea of self-definition in the specification of an artistic medium can be disentangled from both Greenberg’s teleological story and the idea of “essence” that he works with. On Fried’s account, as I understand it, what defines a particular artistic medium is nothing more or less than the evolving histories of artistic and critical practice themselves, and is no more timeless or predictable than they are. This shows another way in which the spatial picture of purity (i.e., what is genuinely “internal” to an artform versus what is merely “external” to it) does more harm than good. What matters is not a medium’s conformity to some previously defined “essence,” but the assumption of responsibility for self-definition. Self-definition which, of course, doesn’t insure artistic success, but provides (some of) the criteria for what is to count as success or failure. It is the refusal of this moment of self-definition, at least in the writings of the Literalist artists Fried takes on, which distinguishes their relation to the idea of a medium of art from a Modernist one.[10]

There is of course a much more detailed story, but even if this correction of Greenberg is accepted, and this placement of the issues of self-definition and medium-specificity is found importantly right, the question I want to raise is how can this vision be brought into alignment with the family of concepts we traced around that of “theatricality” such as to motivate the claim that it is theater, of all things, which lies between the individual arts?

For some help here, I want to turn again to Melville’s “Notes on Allegory” essay. At one point in “Art and Objecthood,” Fried says the following: “… what is wrong with literalist work is not that it is anthropomorphic but that the meaning and, equally, the hiddenness of its anthropomorphism are incurably theatrical” (157). After quoting this passage, Melville offers the following gloss:

What Fried objects to in the work of Tony Smith is the way in which it offers itself to its beholder as (not simply a person but) a person who then refuses to allow one a human relation to itself—it is work that distances itself from (the subject it thereby forces to become merely) its beholder. It refuses to let itself mean—be taken as meaning; it is soulless, it enforces the condition Cavell calls “soul-blindness” on its viewer. We have known people with this kind of irony—who would make us the decider of their ensouledness, who would make us decide for them the humanity of their expressions. (“Notes,” 153)

What strikes me first of all in this passage is the interplay depicted between activity and passivity, specifically activity and passivity as they are implicated together in the very idea of expression. Something is being objected to in this passage, something in connection with the place of expression in Literalist theory and practice. At first the Literalist work is said to refuse to “let itself” mean, or be taken as meaning. Without yet asking just how to understand such a refusal, we can hear in these words a refusal of a kind of passivity or exposure, a refusal to be taken or even “read” by another person as meaning this rather than that. We might then understand such a refusal as a refusal to relinquish a kind of control over one’s field of expression. But the next sentence, which presents itself as a kind of gloss on this one, refers us to a familiar kind of person “who would make us the decider of their ensouledness, who would make us decide for them the humanity of their expressions.” And that sounds like a (fundamental) kind of relinquishment itself, rather than a refusal of such yielding. If this is the same person who is refusing to let himself be read, it is not through an assertion of a kind of dictatorial authority over the true meaning of his expressions (that might be one sort of “refusal”), but rather through an abandonment of any such authority. There is surely something deeply right in this doubleness, this interplay between a kind of passivity and a kind of authority, and that this tells us something important about the conditions of expression in art and elsewhere, and about what “theatricality” could mean in this context, in relation to the issues of medium-specificity and the idea of “theater” in Fried’s sense as that which lies between the arts. And how “theater” could, in a particular historical context, come to seem or be the enemy of art itself.

The story of Modernism that brings literalism and objecthood to bear on the concept of a medium of art begins from a sense, surely undeniable, that insofar as there is a concept of “the modern” in art, it is defined by the fact of crisis in the artist’s relation to the history and conventions of the medium. One of Stanley Cavell’s formulations for this situation is the following from The World Viewed:

Modernism signifies not that the powers of the arts are exhausted, but on the contrary that it has become the immediate task of the artist to achieve in his art the muse of the art itself […] One might say that the task is no longer to produce another instance of an art but a new medium within it. […] It follows that in such a predicament media are not given a priori. The failure to establish a medium is a new depth, an absoluteness, of artistic failure.[11]

The imperative to establish an artistic medium means that the artist herself must somehow assume the authority to determine and declare how her work is to count for us, determine as just what medium of art it is to confront its specific possibilities of success and failure. In art, as well as in ordinary speech and gesture, possibilities of meaning and expression exist only insofar as there are answers to the criterial questions of what sort of thing is the subject of expression here, what speech, what action, what medium of expression. Since this is a matter of establishing and declaring criteria, someone (plural or singular) has to speak with a particular authority here, and have that authority recognized, accepted. This is the moment of self-definition Greenberg saw as defining the task of modernism, but without his assimilation of the tasks of autonomy and self-definition to the aims of purity and exclusivity. Medium-specificity becomes an issue precisely because “media are not given a priori,” and not guaranteed by tradition or placement in history either.

The person “who would have us decide for them the humanity of their expressions” is refusing the authority to declare what he or she is up to and why or how it should count for us. And yet, as we are imagining this scenario, something has just been said, something has been presented or projected, or we are confronted by something in a gallery space. Mere literality, literal literality, is not an option here, and in any case we are confronted here by an inchoate demand for response.[12]

The determination of a medium defines what is to count as artistic success or failure, and hence sets the terms of artistic risk, and thus involves a relinquishing of control (over the response of its audience) for the same reason that it demands an assumption of authority (in making the criterial declaration of a medium itself). The possibilities of expressiveness, whether in art or elsewhere, involve requirements of both types: the assumption of authority to, as it were, speak criterially, and the relinquishing of control over the ultimate destination, or the further reaches of the response being sought out or tested. The Literalist objects and installations can be seen as turning these conditions inside out, for they present themselves as simultaneously refusing all authority to determine a particular medium or mode of expressivness, declaring how this is to count for us, while also insisting on a kind of total control of the situation of the beholder. As if artistic success or failure could be produced through sheer force of control; as if control could do the work of authority. (And from this perspective there is nothing for the beholder to choose between the twin post-modernist strategies of Total Control and Total Chance.)

In this way we can see how something called theatricality could be both part of the pressure of objecthood emerging out of the Greenbergian reading of Modernism’s dialectic of self-definition, and how, as part of this same story, it can be said that “what lies between the arts is theater.” As hopelessly compressed as this is, I hope it also starts the way toward understanding how, in a given time and place, theater in this sense could come to seem the very negation of art, that is, something striking at its very concept, and not simply one of the countless failings (of nerve, of taste, of clarity) that are constitutive risks of any practice of art.

I’ll end with two last remarks. The first is that most of this paper has been a continuous attempt to lead up to the question: “Why isn’t Literalism part of the same motor of self-criticism that Greenberg and others take to be definitive of Modernism?” The answer to that is not entirely in place, of course, but I hope to have ended up posing the question.

Secondly and relatedly, most of my remarks here have discussed these issues somewhat outside of their immediate cultural context. And one of the questions left out by that emphasis is how such a set of concerns could constitute an ideology in the first place; that is, how these conditions of expressiveness, and with them the concept of art itself, could not only come to be repudiated (which may happen for all sorts of reasons, including boredom and incompetence), but also whose abandonment or overcoming could come to be a matter of self-conscious urgency and allegiance to so many of the most ambitious artists and writers of these decades. When it’s more than headline-grabbing, what is it that is really sought for or rallied behind in the various recurrent discourses of the “end of art”? How could such an idea ever be experienced as a matter for taking sides? I would suggest that part of the meaning of these developments can, I think, be seen against the context of Greenberg’s invocation of explicitly Kantian ideas of autonomy and reflexive criticism, and his seeing these as defining of the high modernist project. For that heritage of the high-modernist project provides us with a way of seeing various movements, products, and postures since then, which announce themselves in terms of the end of art as such or position themselves as “anti-aesthetic,” as more or less desperate ways of asserting, what sometimes needs asserting, namely the Kantian as well as post-Kantian idea that it is definitive of the idea of art, as it is of philosophy, that it is bounded by nothing beyond itself, and that it follows from this that only art can bring an end to art.

[1] Stephen Melville, “Notes on the Reemergence of Allegory, the Forgetting of Modernism, the Necessity of Rhetoric, and the Conditions of Publicity in Art and Criticism,” October 19 (Winter 1981): 55-92.

[2] Michael Fried, Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

[3] Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting” (1960) in Modernism with a Vengeance: 1957-1969, ed. John O’Brian, Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism 4 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 86; quoted in Fried, 34-35.

[4] I’m thinking in particular of the first chapter of Melville’s book Philosophy Beside Itself, “On Modernism” (Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota, 1986).

[5] Bruce Glaser, “Questions to Stella and Judd,” in Gregory Battcock, ed., Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology (New York: E.P. Dutton and Co., 1968), 156-57; originally broadcast on WBAI New York in February 1964; quoted in Fried, 151.

[6] Robert Morris, “Notes on Sculpture Part 2,” Artforum 5.2 (October 1966), 23; quoted in slightly abridged form in Fried, 154.

[7]From a talk Fried gave at the 1987 Dia Art Foundation symposium, “Theories of Art after Minimalism and Pop”, in Hal Foster, ed., Discussion in Contemporary Culture, Number One (Seattle, Wash.: Bay Press, 1987), 55-6; quoted in Fried, 40.

[8]There are, of course, other central characterizations of “theatricality” in the essay, which I won’t be taking up here. Perhaps the most seriously neglected one here is the characterization of both Literalist and Modernist works in terms of contrasting modes of temporality.

[9] Not to mention subsequent writings, such as the response to T.J. Clark, “How Modernism Works,” Critical Inquiry 9.1 (September 1982): 217-34.

[10] This “moment” is, of course, an extremely problematic one to describe, let alone to inhabit. How, for instance, are we to begin thinking about what Caro’s table sculptures declare themselves as, determine how they are to count for us? It is not helpful to be told “they are to count as ‘sculpture.’” Nothing less than experience with the evolving practice of the artist can be expected to help here. And perhaps nothing less than the kind of philosophical-critical writing of we’ve been considering can be expected to provide specific content to the idea of “self-definition” or “medium-specificity.”

[11] Stanley Cavell, The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film, enlarged edition (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979), 103.

[12] “But the things that are literalist works of art must somehow confront the beholder—they must, one might almost say, be placed not just in his space but in his way.” (“Art and Objecthood,” 154).

]]>[H]ypostatization is not acknowledgment. The continuing problem of how to acknowledge the literal character of the support – of what counts as that acknowledgment – has been at least as crucial to the development of modernist painting as the fact of its literalness, and that problem has been eliminated, not solved by the artists in question [the literalists]. Their pieces cannot be said to acknowledge literalness; they simply are literal.

—Michael Fried

As we acknowledge the importance of Michael Fried’s critical writings on this fiftieth anniversary of his seminal essay “Art and Objecthood,” it seems opportune to return to one of the fundamental concepts that he wields in his art criticism, that of acknowledgment. Although the term is used only rarely in “Art and Objecthood” itself (once, in footnote 16), it constitutes, through its regular presence in his other critical articles at the time, an essential element of the theoretical framework of the essay. And beyond the utility of reconstructing that framework for our understanding of the essay’s argument, the concept of acknowledgment as used by Fried merits attention in itself as one of his most important insights into the dynamics of the artwork.

As is appropriate for a concept such as acknowledgment, which is predicated upon the interaction of two entities, its role in Fried’s writings has a counterpart in its role in those of Stanley Cavell. In his introduction to Art and Objecthood, Fried speaks of the mutual interest that the two brought to the subject during their conversations that began in 1963.[1] For his part, Cavell speaks of their common focus on acknowledgment as “a continuing discovery of mutual profit.”[2] It is not my intention to enter into a discussion of the relations between the two theorists’ uses of the idea, which would be too long for this essay.[3] Rather I’ll remain with Fried’s analyses of modernist painting and sculpture in which a dynamic within the artwork is understood in terms of acknowledgment, in order to grasp the stakes of this concept when applied to art.

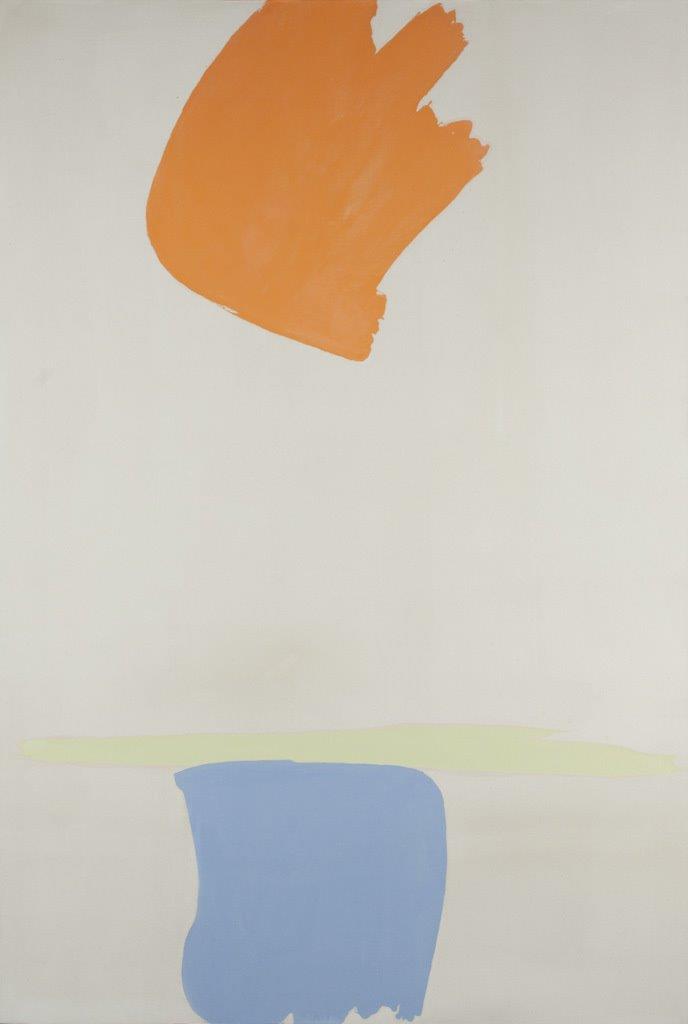

In his 1966 essay “Shape as Form: Frank Stella’s Irregular Polygons” and elsewhere in his early criticism, Fried describes the ways in which various elements of paintings and sculptures, such as a painting’s depicted shapes or a sculpture’s configuration, “acknowledge” the conditions or literal aspects of the medium, such as a painting’s flatness or the shape of its canvas, or a sculpture’s groundedness or placement on a table. For example, the stripes in Kenneth Noland’s diamond-shaped paintings [fig. 1] and in Frank Stella’s early stripe paintings [fig. 2] are said to acknowledge the shape of the support by paralleling it and thus in a way echoing and repeating it: “[Noland’s] four relatively broad bands of color run parallel to one or the other pair of sides, thereby acknowledging the shape of the support” (AO, 83); “Stella’s stripe paintings […] represent the most unequivocal and conflictless acknowledgment of literal shape in the history of modernism” (AO, 88). Likewise, the “zips” or thin vertical lines in Barnett Newman’s paintings [fig. 3] “amount to echoes within the painting of the two side framing edges; they relate primarily to those edges, and in so doing make explicit acknowledgment of the shape of the canvas” (AO, 233). Stella’s irregular polygons take this dynamic a step further by making the relationship between depicted shape and the literal shape of the support more intimate. In Moultonboro III [fig. 4] “the triangle itself comprises two elements – an eight-inch-wide light yellow band around its perimeter and the smaller triangle, in Day-Glo yellow, bounded by that band – both of which seem to be acknowledging, by repeating, the shape of the support” (AO, 89).[4] In these passages, Fried is describing the relation that obtains between the literal shape of the canvas and the shapes of the colored elements within; the colored lines echo, repeat and in a certain way refer to the shape of the support, and thus literal shape is acknowledged by depicted shape.

The analysis highlights the interdependence between these two elements in such a way that they enter into a non-arbitrary relation and are “made mutually responsive” (AO, 77), thereby creating a continuity between the interior and the exterior of the painting which overcomes the duality. This continuity may be seen clearly in the Effingham series [fig. 5], in which the colored bands in some places coincide with the edge of the painting, suggesting the frame and echoing the literal shape, and in others they are integrated into the depicted elements of the painting. The intertwining of the interior and exterior shapes in these paintings “radically recasts, we might say deconstructs, the very distinction between inside and outside” (AO, 63), as Fried wrote concerning Anthony Caro’s sculptures as seen from a Derridian standpoint. Caro’s sculptures likewise acknowledge the conditions of their physicality, whether situated on the ground without a plinth, or on a table. According to Fried, Caro wanted to create sculptures whose actual conditions of placement would not be arbitrary and extrinsic to the particular identity of the work, but would be integrated into, or acknowledged by, its “syntax” or the relations between its parts. His table sculptures [fig. 6] succeed in making their small size a non-contingent aspect of the work – they are not just large sculptures that have been shrunk – by incorporating the table edge into the sculpture’s configuration so that part of the sculpture necessarily hangs off the table, and thus it could not be placed on the ground. That is, their physical conditions and situation are acknowledged by their structure: “the distinction between tabling and grounding, because determined (or acknowledged) by the sculptures themselves instead of merely imposed upon them by their eventual placement, made itself felt as equivalent to a qualitative rather than a quantitative difference in scale” (AO, 190). And, “in the table sculptures, for example, Caro found himself compelled to acknowledge – to find or devise appropriate means for acknowledging – the generic conditions of their inescapable ‘framedness’” (AO, 32-33). It is possible to see this dynamic of acknowledgment at work also in Caro’s ground sculptures, such as Prairie [fig. 7], in which the two horizontal planes created by the row of poles and the sheet of metal echo or acknowledge the horizontality of the ground below, similarly to the way in which Stella’s or Noland’s stripes repeat the literal shape of the canvas. In general, Fried writes, Caro’s abandonment of the plinth participates in this desire to make sculptures that directly acknowledge the literal conditions of their situation: “he was the first to make sculptures which demanded to be placed on the ground, whose specific character would inevitably have been traduced if they were not so placed” (AO, 203). Thus the dynamic in which the work’s literal framing is acknowledged by its interior configuration results in a non-arbitrary relation between the two, overcoming the duality.

In Fried’s careful, detailed analyses of late modernist artworks, he describes various ways in which the literal (physical, material, situated, contingent) properties or conditions of a work are incorporated into it; thus contingency is integrated – and not abolished. His insight recalls Stéphane Mallarmé’s famous integration of chance into poetry in Un coup de dés (“A throw of the dice will never abolish chance”) and Le Livre, in which the contingent nature of the medium of language – and the impossibility ever to abolish this contingency – is acknowledged by the words, syntax and structure of the poems. This is a way of staving off the arbitrariness of the literal medium by integrating it (“absorbing” it, in one of Mallarmé’s formulations); the result is paradoxically a less arbitrary relation between the contingency of the medium and the particular elements of the poem than would have obtained without the direct acknowledgment of that contingency.[5] Thus we might understand Fried’s statement: “Caro on the one hand has frankly avowed the physicality of his sculpture and on the other has rendered that physicality unperspicuous” (AO, 183). Although Fried does use the terms contingency and arbitrariness, (“literal” and “contingent” are associated in his discussion of Caro, for example [AO, 205]), this terminology is not key in his analyses; however, I believe that he would not entirely disagree with their application here. Through the acknowledgment of its own contingency, the work is experienced as being less arbitrary, and (to use Fried’s terms) may thus inspire the beholder’s conviction.

This is the context in which we must understand Fried’s attack on literalism. It is important to recognize, when reading his critique of literalist sensibility in “Art and Objecthood,” that his view of literalness and contingency is not that these should be abolished from artworks (as though that could ever be possible! Mallarmé reminds us that it’s not), but that the literal and contingent properties of a work should be acknowledged and incorporated into it, creating an intimate and non-arbitrary relation between a work’s literal conditions and its configuration, between its situation and its syntax. The problem is not literalness, but what one does with it. The difficulty with minimalist works is that they cannot acknowledge their own literalness – not because there is nothing to acknowledge (they do have literal conditions and shape) but because there is nothing in them to do the acknowledging. They have no parts, no configuration, no syntax capable of entering into relation with their literalness; they are “hollow” (AO, 151). As unitary works, they “hypostatize” literalness as such, simply manifesting their literal conditions, and thus remain arbitrary. The trouble is not literalness itself, then, but literalness in itself. This is how we should understand the phrase cited in my epigraph, “hypostatization is not acknowledgment,” which is key to understanding “Art and Objecthood” and might ring as somewhat cryptic if this background isn’t clear. “[Literalist] pieces cannot be said to acknowledge literalness; they simply are literal” (AO, 88). In Stella’s irregular polygons, on the other hand, literalness “is no longer experienced as the exclusive property of the support. Rather, it is suffused more generally and, as it were, more deeply throughout them” (AO, 92-93). As Mallarmé would say, it is “absorbed,” thus overcoming the distinction between outside and inside. Literalness is not antithetical to the modernist artworks that Fried advocates, which do not abolish but rather acknowledge their literalness and contingency. This is what is meant when Fried states that shape “must be pictorial, not, or not merely, literal” (AO, 151, emphasis added). Objecthood, then, in Fried’s terminology, is not synonymous with literalness, but would be the result of the simple hypostatization or manifestation of literalness, rather than its acknowledgment.

Fried insists on the historically contingent nature of the literal conditions and properties that a given artwork may be said to acknowledge at any given time. That is, the object of acknowledgment is proper to every work and not generalizable to any ahistorical, essential qualities of a medium, which do not exist. (See Fried’s critique of Clement Greenberg’s essentialism [AO, 33-40].) Furthermore, the process of acknowledgment, the dynamic of relations that may be created between the inside and outside of a work, is also proper to every work, artist and period. “It is a historical question what in a given instance counted as acknowledging one or another property or condition of that medium, just as it is a historical question how most accurately to describe the property or condition that the acknowledgment was of. (The determining properties or conditions of a medium in a given instance might be virtually anything; at any rate, they can’t simply be identified with materiality as such.)”[6] That which is acknowledged, as well as that which a beholder may perceive as a dynamic of acknowledgment between the configurations, images, “syntax” or other elements and their literal conditions – ultimately, that which compels a beholder’s conviction in this dynamic – is historically contingent and changing.[7]

Fried’s focus on historicizing the properties of an artwork and the dynamic of acknowledgment participates in his critique of Greenberg, for whom the development of modernism consisted in the progressive manifestation of a medium’s “irreducible essence” – which, Fried argues, resulted in literalism.[8] According to Fried, the literalists’ hypostatization of literalness is simply the endpoint of Greenberg’s modernist reduction of a medium to its essential and literal qualities. It is important to note that despite a certain similarity of vocabulary, the process Greenberg describes in “Modernist Painting” and elsewhere is quite different from the dynamic of acknowledgment that Fried analyses.[9] For Greenberg, art’s movement of self-declaration is one of gradual, “radical simplification” of the medium; a modernist work explicitly indicates its properties “in order to exhibit them more clearly as norms. By being exhibited, they are tested for their indispensability.”[10] If not indispensable, they will be shed. The evolution is toward purification and ever greater explicitness of the medium’s “essence.” Whereas Greenberg describes a sort of hollowing out of the insides of painting as it becomes all surface, Fried emphasizes the intimate relations created between the interior configuration of a work and its material conditions, as its literal properties are acknowledged by its depicted elements.

In his later writings, Fried associates the idea of explicitness with Greenberg’s version of modernist self-criticism and the literalism it produced, and attempts to keep it separate from the concept of acknowledgment. In a footnote to his introduction to Art and Objecthood Fried laments that in his early critical writings he often used the two together.[11] However, the concepts are indeed difficult to separate, and ultimately he need not worry. The problem with Greenberg’s theory was not the concept of explicitness, but his idea of a progressive purification or reduction to mere explicitness. (Just as the problem with literalness is not the fact of literalness, as I argued above, but mere literalness, nothing but literalness.) It would be impossible entirely to separate the concepts of acknowledgment and explicitness; acknowledgment implies the act of bringing something to light, expressing something, rendering something clear either in deed, words or conscious awareness. In art, the relations between depicted elements and physical conditions become evident to a beholder through the dynamic we have been calling acknowledgment. As Cavell writes, “Acknowledgment ‘goes beyond’ knowledge, […] in the call upon me to express the knowledge at its core, to recognize what I know, to do something in the light of it, apart from which this knowledge remains without expression, hence perhaps without possession.”[12] And elsewhere, acknowledgment “goes beyond [knowledge] in its requirement that I do something or reveal something on the basis of that knowledge.”[13] The act of acknowledgment inevitably involves something passing from a less to a more explicit state, even if that takes place only within one’s own consciousness. Cavell, again: “[Acknowledgment] is like something hidden in consciousness declaring itself. The mode is revelation. I follow Michael Fried in speaking of this fact of modernist painting as an acknowledging of its conditions.”[14] While acknowledgment always comprises (can never abolish) some kind of explicitness, neither can it be identified with simple exhibition, mere explicitness. As with literalness, what counts with explicitness is what one does with it; literalism does nothing but explicitly exhibit its partless singularity, while in modernism a work’s configuration explicitly integrates – acknowledges – its conditions. Thus we may prize the concept of explicitness away from Greenberg’s use of it.

We should distinguish the concept of acknowledgment from that of self-critique, as theorized by Greenberg, as well as from the other “self-” prefixed terms he uses such as self-declaration, self-definition, self-confession. This focus on the self-activity of a medium or an artwork foreshadows minimalism’s wholeness or unitary character, criticized by Fried in “Art and Objecthood.” The problem, again, is that this self-manifestation is conceived as not having parts or internal relations; there is only one element (or, for Greenberg, extraneous elements will eventually be discarded). I began by mentioning the fact that acknowledgment is predicated upon the interaction of two entities (x acknowledges y), and have gone on to show how in Fried’s analysis of art this process leads to a mutual responsiveness and a continuity between the two which overcome the duality. Ultimately, in a sense, both minimalism and modernism sought non-dualism, though through radically different routes – minimalism by manifesting simple, literal singularity and wholeness, modernism by entering into a dynamic of co-implication, intertwining and acknowledgment. Minimalism pretends to arrive at non-dualism by simply eliminating duality and positing unity by fiat; modernism by the much more difficult route of acknowledging alterity and overcoming duality through creating non-arbitrary relations.

Acknowledgment is an anthropomorphic concept when applied to art, as it is normally a human act. It implies notions of consciousness, communication and sincerity. Fried’s criticism of the anthropomorphism of literalism in “Art and Objecthood” is not aimed at anthropomorphism as such, but at the insincere and theatrical manifestations of it he saw in literalist art (“what is wrong with literalist work is not that it is anthropomorphic but that the meaning and, equally, the hiddenness of its anthropomorphism are incurably theatrical” [AO, 157]). What would an anthropomorphic artwork be like that is not hollow or just a theatrical surface, but one that is human and sincere?[15] One answer is a work that explicitly acknowledges its own conditions, framedness, contingency. And to follow out the analogy, what would it mean for a human to acknowledge her or his own literal conditions, situation, materiality, framedness (in time…), internal alterity? Acknowledging one’s own contingency is not a simple matter (try it). Nor is it simple to create artworks that invite beholders to ask such questions, and to search themselves for answers. These are the stakes of modernist acknowledgment.

[1] Michael Fried, “An Introduction to My Art Criticism,” in Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 37 (henceforth AO).

[2] Stanley Cavell, The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979), 239. He writes, “The concept of acknowledgment first showed its significance to me in thinking about our knowledge of other minds, in such a way as to show (what I took to be) modern philosophy neither defeating nor defeated by skepticism. It showed its significance to Michael Fried in characterizing the medium or enterprise of the art of painting” (239).

[3] For Cavell’s discussions of painting and film in terms of acknowledgment, see especially The World Viewed, 108-26; on the role of acknowledgment in his arguments on skepticism, see Must We Mean What We Say? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976), 238-66, and The Claim of Reason: Wittgenstein, Skepticism, Morality, and Tragedy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), 329-496.

[4] The term “acknowledgment” was intended to replace Fried’s earlier conception of “deductive structure,” a more deterministic or mechanistic formulation, referring to the way in which the stripes in Stella’s early stripe paintings, for example, echo or are derived from the literal shape of the painting. (See AO, 23-4.) A lingering association of the idea of acknowledgment with this form of simple (parallel) repetition seems to explain the statement in “Shape as Form” that Stella’s irregular polygons do not acknowledge literal shape (AO, 94); however, a few pages earlier Moultonboro III is analyzed in terms of acknowledgment.

[5] Stéphane Mallarmé, “Igitur,” in Oeuvres Complètes, 2 vols., ed. Bertrand Marchal (Paris: Gallimard, 1998-2001), 1:478.

[6] Michael Fried, Courbet’s Realism (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1990), 285.

[7] For example, he sees in Manet’s paintings of the 1860s an acknowledgment of “the primordial convention that paintings are made to be beheld,” Manet’s Modernism, or, The Face of Painting in the 1860s (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 405; see also Courbet’s Realism, 286.

[8] Clement Greenberg, “After Abstract Expressionism,” in The Collected Essays and Criticism, Vol. 4: Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957-1969 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 131. See also “Sculpture in our Time” and “Modernist Painting” in the same volume, as well as Fried’s discussion in AO, 33-40 and 66. “Literal” is a term used often by Greenberg in his criticism (for example, in “Sculpture in our Time”) although not with the consistent philosophical charge used by Fried.

[9] It is possible that in the concept of acknowledgment we may witness Fried prizing the term away from Greenberg’s theorizing, with Cavell’s help, thus overcoming the influence of the elder critic.

[10] Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” 89.

[11] “Unfortunately, I continued to deploy the concept of explicitness in connection with that of acknowledgment in ‘Shape as Form’ and subsequent essays, which I think was a mistake: part of the point of stressing acknowledgment in those contexts was to avoid the pitfalls of the idea of making explicit, and I wish I had kept the two terms rigorously separate. And yet the fact that I did not, indeed that the phrases ‘explicit acknowledgment’ and ‘explicitly acknowledge’ came so readily to hand, suggests that the distinction in question was (and, I think, still is) conceptually insecure. I’m not sure what to do about this other than to call attention to the problem” (AO, 65). See also Courbet’s Realism, 285.

[12] Cavell, The Claim of Reason, 428; cited by Michael Fried, Courbet’s Realism, 364.

[13] Cavell, Must We Mean What We Say? 257.

[14] Cavell, The World Viewed, 109.

[15] See Lisa Siraganian, “Art and Surrogate Personhood,” nonsite.org 21 (July 2017): n.p.; https://nonsite.ecdsdev.org/article/art-and-surrogate-personhood-2

]]>Specifically, “Art and Objecthood” was meant to offer a corrective to an overly simplistic understanding of modernism that had taken hold in the decade or so prior to the essay’s publication. Minimalism, Fried suggested, was a product of that misprision. He explained:

[O]bjecthood has become an issue for modernist painting only within the past several years. This, however, is not to say that before the present situation came into being, paintings, or sculptures for that matter, simply were objects. It would, I think, be closer to the truth to say that they simply were not. The risk, even the possibility, of seeing works of art as nothing more than objects did not exist. That such a possibility began to present itself around 1960 was largely the result of developments within modernist painting. Roughly, the more nearly assimilable to objects certain advanced paintings had come to seem, the more the entire history of painting since Manet could be understood—delusively, I believe—as consisting in the progressive (though ultimately inadequate) revelation of its essential objecthood, and the more urgent became the need for modernist painting to make explicit its conventional—specifically, its pictorial—essence by defeating or suspending its own objecthood… (160)

Although the text implies 1960 is merely a ballpark date, it seems relevant to note that Clement Greenberg’s “Modernist Painting” was published in precisely that year.1 Recalling this, we may be tempted to hear the sentence in question punctuated somewhat differently: “That such a possibility began to present itself around 1960 was largely the result of developments within ‘Modernist Painting’.” I have to think that, whatever Fried’s allegiances at the time to Greenberg, he could only have been dismayed at the form Greenberg’s argument had taken in that essay.2 Instead of a nuanced account premised on the careful observation and description of specific works, “Modernist Painting” offered an overly reductive, insufficiently dialectical and fundamentally misleading understanding of the modernist project. In many ways the charge that Fried would level at Minimalism, that it sought “to declare and occupy a position—one that can be formulated in words” (148), might just as easily have been directed at Greenberg’s essay. As presented there, modernism entailed an incremental, “purifying” reduction to its essence of each individual medium. “Manet’s became the first Modernist pictures,” Greenberg asserted, “by virtue of the frankness with which they declared the flat surfaces on which they were painted.”3 “Because flatness was the only condition painting shared with no other art,” he continued, Modernist painting oriented itself to “the ineluctable flatness of the surface” as it did to nothing else (“Modernist Painting,” 87).

I’d like to think it goes without saying that this formulation amounts to a caricature of the models of modernism put forward in many of Greenberg’s other critical writings. In “Collage,” for example, which was written only the year before “Modernist Painting,” the picture is considerably more complicated. Rather than recounting a simple linear progression to an essence, “Collage” presents Cubism’s development as fully dialectical. There, the medium of painting is seen to draw in certain (self-)critical moments on the resources of, first, sculpture and, subsequently, papier collé. Even more importantly, “Collage” discusses the literal flatness of its material support as a condition that modernist painting felt obliged to own up to, but with which it refused to be fully reconciled. “Painting had to spell out, rather than pretend to deny, the physical fact that it was flat,” Greenberg writes in “Collage,” “even though at the same time it had to overcome this proclaimed flatness as an aesthetic fact” were it to become a successful painting.4 It was, in this accounting, precisely its non-reconciliation to “the ineluctable flatness of its surface” that drove the production of modernist painting. Far from serving as the essence of the medium, the literal or material support was something that had to be negated or otherwise undone.5

A related logic can be seen at work within “Art and Objecthood” and Fried’s other critical writings of the period—although in them literal shape and, by extension, objecthood have taken over the role played by physical or “undepicted” flatness in Greenberg’s “Collage.” In both cases what is fundamentally at stake is a distinction between the realized work of art and other, more superficial sorts of things (wallpaper, for example, as Picasso’s papiers collés make clear, or mass-produced commodities).6 Admittedly, Fried doesn’t phrase matters this way. He continues to refer to “literalist art” and to associate it with theater—which is to say, not with non-art but simply with another recognized artistic form—thereby holding the greater threat at bay and effectively inoculating Minimalism against any more serious charge.7 Still, as Stephen Melville has argued, the anxiety driving the critical projects of both Greenberg and Fried is indissociable from the context of late capitalism.8 It is also wholly understandable; “it is based,” Melville writes, “on the way things of culture increasingly do appear to die, to cease to count, in our world: not with a bang, but a whimper. It is, among other things, fear of Muzak” (Philosophy Beside Itself, 8).

Again, it seems to me that Fried’s antipathy toward Minimalism is fueled by just such concerns. For him, the work of art is successful only insofar as it’s able to both acknowledge its factual objecthood and to somehow defeat or suspend it. In the case of the paintings he most admires, that conflict is played out principally within the “medium” of shape. As he explains it in his discussion of Frank Stella’s irregular polygons, it “is only in the presence of this conflict that the question of whether or not a given painting holds or stamps itself out as shape makes full sense—or rather, only here that the issue of ‘the viability of shape as such’ characterizes a specific stage in resolving or unfolding problems of acknowledgment, literalness, and illusion which…have been among the issues of modernism from its beginning.”9 If the irregularly shaped canvas of Stella’s Moultonboro III (1966) raises the prospect of objecthood—much as had his earlier metallic stripe paintings (e.g., Ileana Sonnabend, 1963)—Moultonboro III nonetheless manages to neutralize any temptation on our part to regard its depicted shapes as dependent on its literal one. Rather, Fried points out, the depicted and the literal appear wholly continuous with one another. We immediately perceive Moultonboro III as comprising a triangle superimposed upon a square, those shapes “acknowledging, by repeating, the shape of the support” (89). Yet it seems even truer to our experience of the painting to say that the depicted shapes undo the primacy of the literal support: “The beholder is in effect compelled not to experience the literal shape in its entirety—as a single entity—but rather to perceive it segment by segment, each of which is felt to belong to one or another of the smaller shapes that constitute the painting as a whole” (90).

Furthermore, in Moultonboro III those smaller shapes seem to exist in uncertain relation in depth both to one another and to the surface of the picture. Fried describes the spatial relation between “the light yellow triangular band” and “the turquoise blue Z-shaped band into which it fits” as “ineluctably ambiguous” (“Shape as Form,” 93). (Note that, in choosing that particular word, “ineluctably,” Fried is not only describing an aspect of Moultonboro III but also marking his growing differences with Greenberg, especially the Greenberg of “Modernist Painting.” Where the latter had identified the “ineluctable flatness of the support” as the very essence of painting, Fried suggests that what appears most ineluctable in the paintings he admires is their pervasive ambiguity.) The beveled ends of the Z, and the fact that its top and bottom segments do not run parallel to one another, introduce suggestions of obliquity that undermine the factual certainty of the shape. In this regard, too, Fried says, Moultonboro III is exemplary of Stella’s irregular polygons, the best of which make “literalness illusive” (95). “[B]y so doing,” he adds, “they unmake, at least in the event and for the moment, the distinction between shape as a fundamental property of objects and shape as an entity belonging to painting alone…” (96).

Despite their status as mere prepositional phrases, Fried’s qualifying “in the event and for the moment” signal another significant departure from Greenberg. Even the Greenberg of “Collage” had implied that the optical illusiveness of the papiers collés resolved once and for all the conflict between literal and depicted flatnesses that had driven earlier Cubist production. However much Fried may feel that Stella’s irregular polygons constitute a similarly compelling response to the “unfolding problems of acknowledgment, literalness, and illusion” characteristic of modernism, he knows that those problems will continue to unfold. “Solutions” are ever only provisional because history is ongoing. In their unfolding, even the problems themselves are bound to change their shape.

Today, half a century after the publication of “Art and Objecthood” and “Shape as Form,” Fried’s characterization of Minimalism still holds sway—except, of course, for his negative assessment of that work. As he himself has remarked, the terms of his argument have gone largely untouched, even (or perhaps especially) among his critics; they have merely reversed the terms’ original values (“An Introduction,” 43). My own relation to the essay is rather less straightforward. On the one hand, I’m reluctant to subsume Judd’s work in particular to the category of the merely theatrical. It seems to me preferable to discount much of his rhetoric and so to see his wall pieces, as others have, in relation to sculpture or painting rather than as “specific objects.”10 Viewed from this angle, the wall pieces frequently evince a pictorialism or perceptual excess that might well be regarded as continuous with modernism’s earlier unfolding. On the other hand, I deeply share Fried’s concern that art might become—or might now, in 2017, have already become—trivialized, all but entirely displaced by a set of “openly theatrical productions and practices” (“An Introduction,” 43). Here Carsten Höller’s giant slides for the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern readily come to mind…

Hegel believed that it was incumbent on anything that wanted to be taken seriously to “prove its object,” which is to say, to show itself to be the kind of thing that it in fact is. I am enough of a Hegelian (and a modernist) to feel that art must still “prove its object,” each work somehow making visible a claim for its existence as a work of art rather than some other sort of thing. I take it that what Fried has wanted to show us, not only in his early writings but throughout his art-historical career, is that such “objectivity” is at consequential odds with mere “objecthood,” and that both art and art history need to be clear about those stakes, at least if they hope to be taken seriously. In that sense above all “Art and Objecthood” continues to be for me an extremely consequential text.

Notes

What we have in the tradition of this comparative understanding is a deeply entrenched syncretic belief system. It is a system that mixes two different forms together, like the uniting of early Christian religion with Roman law to produce the Roman Catholic Church. The art of painting has been married to the structure of language since the early church declared painting acceptable as the visual bible for the illiterate. This system unites “painting”—a site-specific material-based form of art—with “language”—a form of communication that is separate from what it signifies, and defers materiality to the category of mere craft. This syncretic system interprets all the arts as being language-based, and this justifies the art of painting as a picture-language. Picture-paintings tell a story.

The origin of the concept of a scholars’ library for the study of the arts comes from the nine daughters of Zeus, the first four of which are forms of poetry, two of theater, two of music and dance, and the ninth, astronomy. These muses preside over learning and the creative arts. There is, in this tradition, no muse of the material arts, no muse of painting or sculpture.

Writers on the comparison of the arts were, of course, looking at picture-paintings, and most of them readily admit that they are not actually referring to painting per se, but rather to the visual image in general. Lessing, in his introduction to “Laocoön,” states clearly that by “painting” he means the visual arts in general, and by “poetry” the arts whose composition is progressive in time. The problem inherent in the belief that painting is a picture-language can be played out in the Galilean drama of seeing versus perceiving. In 1632, when Galileo presented his support of the Copernican heliocentric model of our solar system, his argument was based in part on his direct observations of the planets through the new technology of his telescope, and this was done against the fixed authority of the established theory. Now consider that Maffeo Barberini, who was schooled in the traditional Ptolemaic geocentric system, could have said to Galileo, “Everyday I see the sun rise in the East, move across the sky, and set in the West. I observe the sun revolve around the Earth.” His argument would not only have been backed by 1,400 years of tradition, but also by what he saw. Had Pope Urban VIII made this argument in 1633, he may not have understood that his interpretation of what he sees in the sky was not evidence of the sun revolving around the earth. The reason we think we see the sun rise is not that the sun revolves around the earth, but rather that the earth rotates on its own axis. The problem lies in perceiving the power of the earth’s turning. When looking at a picture-painting, do you perceive the power of its material? If you don’t recognize the painting as a material object, you might as well be looking at a photographic reproduction. The reproduction (adjusted to fit the format of your screen) will also give you the information of the picture. It too tells the story.

There are now more reproductions of the visual arts in the world than there are original works, and these reproductions are an established educational tool that serves a very useful function (as any art historian will tell you). But keep in mind, the photographic reproduction of the visual work of art is to the original object what pornography is to sex. The actual painting is material-based, and therefore motivated by sensibility. Everything else is virtual reality.

We think of a painting as a picture-language not as a dismissive pejorative, but rather because of our fundamental belief that a painting is an image rather than an object, and that its energy is derived from the viewer’s imagination. Our concept of image separates the image from what it is an image of, and what we defer is our attention to materiality of the image. The questions we often hear asked about abstract painting—what does it represent, or what is it trying to express?—are seeking to know what its identity is abstracted from.

In the visual arts, our understanding of image is based on the Greek concept of mimesis, and is derived in part from Plato’s concept of ‘eikonos,’ icon, which is defined by shadow and reflection. The concept of image has only a resemblance or an allusion to a prototype, and the idea of re-presentation. So our sense of the unity of the picture-painting is dependent on something outside the sensibility of the actual paint material.

The invention of the camera allowed the separation of the binary coupling of picture and painting, and like Galileo’s telescope, which helped the science of astronomy to divorce itself from the ninth daughter of Zeus, painting no longer had to represent itself as a theater tableau to be judged by the standards of some other form. So its successful realization now does not depend on the establishment of the supreme fiction of its own nonexistence as an object on the wall. In the pursuit of modern art, we should recognize that not only do we have a habit of speech that informs our method of discovery, but also a belief system that paintings, no matter how abstract, are composed like a language. They are understood as tribal images that convey meaning. So many of the questions we ask are seeking a criterion of correctness, some Rosetta Stone that will allow us to interpret the inferences and shared beliefs of the culture the painting represents.

You can trace the liberation of painting from the structure of a picture-language by simply following the gradual removal of the picture frame from the practice of painting. Through the 20th century, it is a transition out of the composition of a picture-form and into the structural identity of the painted-form, a paradigm shift from pictorial representation to concrete actualization.

By the time Michael Fried published “Art and Objecthood” in 1967, this transition had been in development for over 50 years and was beginning to take on a life of its own. Some painters were investigating the materials of their practice, not in terms of the craft of the painting’s making, but rather in recognition of the force with which those materials affect the viewer. It was to bring into the conscious forefront of the experience of the painting considerations of the conditions of application, boundary, color, scale, and presentation.

There was also an acknowledgment on the part of some art world intellectuals that in order for something to be understood as a modern painting, it required the recognition of certain unalienable conditions of the painting itself. This notion questioned issues such as the construction of the support, its relationship to the wall, its shape and surface, and how the fact of its materials could identify the object as a painting. It brought to the forefront of the discourse on modern art the body problem, not the fictitious body of the image, but rather the concrete actuality of the painting on the wall as an object, and by extension, what is required for it to be recognized as a successful painting.

Many of the painters and writers on modern painting at that time tried to imbue the work with the rhetoric of mystic transcendence or psychological expression, because once you begin to address the body problem of the painting itself, it immediately raises the more fundamental and deeply rooted question as to what then motivates that body and what is the effect of its power.

It is clear that our concept of image and our understanding of language are compatible theories, in that neither is dependent on the specificity of the material’s visual sensibility. All the paintings that Wallace Stevens makes reference to in 1951 are also pictures/images, and in his view, they are motivated by the imagination. Today his remarks about painting might also apply to television, movies, and computer games, which are all forms of picture-language. And would Lessing now have to classify those forms of image-making in the category of poetry, because their composition is progressive in time?

This change from a concern for the relationship between the arts, in which all the arts come under the umbrella of language in order to neutralize the material difference between them, to the acknowledgment of the discrepancy between the image and its materiality, seems to center in the visual arts on the investigation of the specifics of each art form’s physical identity. By the mid-20th century, the subject of modern painting was, at least in part, the recognition of the painting itself as a sensory object on the wall. This, of course, raised questions about the independent nature of sensory experience, and its relationship to understanding.

*

In 1962, Clement Greenberg published an article in Art International titled “After Abstract Expressionism,” focusing on the materiality of modern painting. This came after his 1955 article in Partisan Review, “‘American-Type’ Painting,” in which he embraces the work of the abstract expressionists, and his 1960 essay, “Modernist Painting,” in which he presents the rationale of (but does not advocate for) modern art. Greenberg’s critique of modern art in part comes from his understanding of Kant’s “Critique of Aesthetic Judgment.” The aesthetic condition of art, Greenberg believed, should be valid solely on its own terms, and so as a guarantee of its quality, the art needed to distance itself from the culture in which it was produced. This meant that it had to dispense with any unwanted conventions in order not to dilute the intensity and seriousness of its art. The art was to maintain the continuity of each form, while at the same time discarding all the unrelated stuff from that form. The enterprise of painting was subject to the self-critique of its own practice.

Greenberg proposed in “After Abstract Expressionism” that “by now it has been established, it would seem, that the irreducible essence of pictorial art consists in but two constitutive conventions or norms: flatness and the delimitation of flatness.” For the art of painting, he concluded, “the observation of merely these two norms is enough to create an object which can be experienced as a picture: thus a stretched or tacked up canvas already exists as a picture—though not necessarily as a successful one.” This proposition about the irreducible essence of pictorial art became somewhat axiomatic in the account of modern visual arts. It is easy to imagine yourself standing in a room with two other objects, a sculpture on the floor, and a painting on the wall. The question is then posed as to their unique difference. It was no longer about their common identity as works of art—it was, rather, what sets each form apart from the others. For Greenberg, in this instance, it is simply the fact of them as physical objects.

Greenberg argued that “to achieve autonomy, painting has had above all to divest itself of everything it might share with sculpture.” He rejected color as an essential element specific to painting, because sculpture and theater also have color. He acknowledged that paintings are material objects in the world, like sculpture, but unlike sculpture paintings have this particular quality of flatness as an object: a “two-dimensional entity in space.” His acknowledgment of painting as an object, albeit a flat wall object, is to the history of painting what Copernicus’ recognition of our solar system was to the history of astronomy. It is the recognition that a painting is not just a surface wall decoration, in the same way that a sculpture is not just an extended gargoyle of a building. A painting is an object that has a relationship to a wall in the way a sculpture is an object that has a relationship to a floor, and these are related but different functions. This acknowledgment, that the recognition of the physical body of the painting is essential to our understanding of painting as a modern work of art, is crucial for the understanding of the transformation that the practice of painting is making towards its own actualization.

One of the things about the history of the easel form of painting that is often overlooked is that the painting itself became independent of architecture and could be transported from one place to another. However, the painting’s physicality was understood merely as making it possible to transport cultural cargo through time and space. Most of the art historical theories focused on the cargo, not the vessel. For Greenberg, it was a particular condition of painting as a vessel that distinguished it from sculpture: “flatness and the delimitation of flatness.”

Greenberg defined modern painting to be independent of other art forms, and stressed the development of painting’s uniqueness as being only accessible to sight. As he said, the experience of the painting is “one of purely optical experience, against optical experience as revised or modified by tactile association.” This seems to me a clear rejection of the now-fashionable art-world reference to Freud’s notion in “Sexual Aberrations” that seeing is “an activity that is ultimately derived from touching.” While that may be true for pornography and photographic reproductions, consider the fact that if I put a painting into the hands of a blind person, they could tell you that it is a flat object. What they cannot tell you is what color it is. So again, imagine yourself in a room with two other objects. This time, a chair on the floor, and a flat-screen TV on the wall. The question again is posed as to their unique difference. Since they do not share the common bond of being works of art, the tendency is to think of their use-function. Their difference is that you sit down in the chair to watch images on the television. But should we now also consider the flat-screen TV to be a painting, albeit not a successful one until it is turned on? The problem, of course, is obvious. Not only did Greenberg have a habit of speech in referring to paintings as pictures, but he conceives of the art of painting as a picture-language, and for image-making, his axiom about “pictorial art” seems essentially true.